| School Information System |

| Sponsorships | Sponsorships |

|

|

Alastair Creelman & Linda Reneland-Forsman:

Statistics are often used to reveal significant differences between online and campus-based education. The existence of online courses with low completion rates is often used to justify the inherent inferiority of online education compared to traditional classroom teaching. Our study revealed that this type of conclusion has little substance. We have performed three closely linked analyses of empirical data from Linnaeus University aimed at reaching a better understanding of completion rates. Differences in completion rates revealed themselves to be more substantial between faculties than between distribution forms. The key-factor lies in design. Courses with the highest completion rates had three things in common; active discussion forums, complementing media and collaborative activities. We believe that the time has come to move away from theoretical models of learning where web-based learning/distance learning/e-learning are seen as simply emphasizing the separation of teacher and students. Low completion rates should instead be addressed as a lack of insight and respect for the consequences of online pedagogical practice and its prerequisites.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Alison Gopnik

Changes in our environment can actually transform the relation between our traits and the outside world.

We all notice that some people are smarter than others. You might naturally wonder how much these differences in intelligence depend on genes or upbringing. But that question, it turns out, is impossible to answer. That's because changes in our environment can actually transform the relationship among our traits, our upbringing and our genes.

The textbook illustration of this is a dreadful disease called PKU. Some babies have a genetic mutation that makes them unable to process an amino acid in their food, and it leads to severe mental retardation. For centuries, PKU was incurable. Genetics determined whether someone suffered from the syndrome, which gave them a low IQ. Then scientists discovered how PKU works. Now, we can immediately put babies with the mutation on a special diet. Whether a baby with PKU has a low IQ is now determined by the food they eat--by their environment.

We humans can figure out how our environment works and act to change it, as we did with PKU. So if you're trying to measure the relative influence of human nature and nurture, you have to consider not just the current environment but also all the possible environments that we can create. This doesn't just apply to obscure diseases. In the latest issue of Psychological Science, Timothy C. Bates of the University of Edinburgh and colleagues report a study of the relationship among genes, SES (socio-economic status, or how rich and educated you are) and IQ. They used statistics to analyze the differences between identical twins, who share all DNA, and fraternal twins, who share only some.

When psychologists first started studying twins, they found identical twins much more likely to have similar IQs than fraternal ones. They concluded that IQ was highly "heritable"--that is, due to genetic differences. But those were all high SES twins. Erik Turkheimer of the University of Virginia and his colleagues discovered that the picture was very different for poor, low-SES twins. For these children, there was very little difference between identical and fraternal twins: IQ was hardly heritable at all. Differences in the environment, like whether you lucked out with a good teacher, seemed to be much more important.

In the new study, the Bates team found this was even true when those children grew up. IQ was much less heritable for people who had grown up poor. This might seem paradoxical: After all, your DNA stays the same no matter how you are raised. The explanation is that IQ is influenced by education. Historically, absolute IQ scores have risen substantially as we've changed our environment so that more people go to school longer.

Richer children have similarly good educational opportunities, so genetic differences among them become more apparent. And since richer children have more educational choice, they (or their parents) can choose environments that accentuate and amplify their particular skills. A child who has genetic abilities that make her just slightly better at math may be more likely to take a math class, so she becomes even better at math.

But for poor children, haphazard differences in educational opportunity swamp genetic differences. Ending up in a terrible school or one a bit better can make a big difference. And poor children have fewer opportunities to tailor their education to their particular strengths. How your genes shape your intelligence depends on whether you live in a world with no schooling at all, a world where you need good luck to get a good education or a world with rich educational possibilities. If we could change the world for the PKU babies, we can change it for the next generation of poor children, too.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Earlier this week, I spotted, among the job listings in the newspaper Reforma, an ad from a restaurant in Mexico City looking to hire dishwashers. The requirement: a secondary school diploma.Years ago, school was not for everyone. Classrooms were places for discipline, study. Teachers were respected figures. Parents actually gave them permission to punish their children by slapping them or tugging their ears. But at least in those days, schools aimed to offer a more dignified life.

Nowadays more children attend school than ever before, but they learn much less. They learn almost nothing. The proportion of the Mexican population that is literate is going up, but in absolute numbers, there are more illiterate people in Mexico now than there were 12 years ago. Even if baseline literacy, the ability to read a street sign or news bulletin, is rising, the practice of reading an actual book is not. Once a reasonably well-educated country, Mexico took the penultimate spot, out of 108 countries, in a Unesco assessment of reading habits a few years ago.

One cannot help but ask the Mexican educational system, "How is it possible that I hand over a child for six hours every day, five days a week, and you give me back someone who is basically illiterate?"

...

This is not just about better funding. Mexico spends more than 5 percent of its gross domestic product on education -- about the same percentage as the United States. And it's not about pedagogical theories and new techniques that look for shortcuts. The educational machine does not need fine-tuning; it needs a complete change of direction. It needs to make students read, read and read.

But perhaps the Mexican government is not ready for its people to be truly educated. We know that books give people ambitions, expectations, a sense of dignity. If tomorrow we were to wake up as educated as the Finnish people, the streets would be filled with indignant citizens and our frightened government would be asking itself where these people got more than a dishwasher's training.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Peer reviews of conference paper submissions is an integral part of the research cycle, though it has unknown origins. For the computer vision community, this process has become significantly more difficult in recent years due to the volume of submissions. For example, the number of submissions to the CVPR conference has tripled in the last ten years. For this reason, the community has been forced to reach out to a less than ideal pool of reviewers, which unfortunately includes uninformed junior graduate students, disgruntled senior graduate students, and tenured faculty. In this work we take the simple intuition that the quality of a paper can be estimated by merely glancing through the general layout, and use this intuition to build a system that employs basic computer vision techniques to predict if the paper should be accepted or rejected. This system can then be used as a first cascade layer during the review pro- cess. Our results show that while rejecting 15% of "good papers", we can cut down the number of "bad papers" by more than 50%, saving valuable time of reviewers. Finally, we fed this very paper into our system and are happy to report that it received a posterior probability of 88.4% of being "good".1. Introduction

Peer reviews of conference paper submissions is an in- tegral part of the research cycle, though it has unknown origins. For the computer vision community, this process has become significantly more difficult in recent years due to the volume of submissions. For example, the number of submission to the CVPR conference has tripled in the last ten years1 (see Fig. 1). For this reason, the commu- nity has been forced to reach out to a less than ideal pool of reviewers, which unfortunately includes uninformed ju- nior graduate students, disgruntled senior graduate students,

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

If ramen noodle sales spike at the start of every semester, here's one possible reason: textbooks can cost as much as a class itself; materials for an introductory physics course can easily top $300.Cost-conscious students can of course save money with used or online books and recoup some of their cash come buyback time. Still, it's a steep price for most 18-year-olds.

But soon, introductory physics texts will have a new competitor, developed at Rice University. A free online physics book, peer-reviewed and designed to compete with major publishers' offerings, will debut next month through the non-profit publisher OpenStax College.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Research supports parental involvement as a viable means of enhancing children's academic success. Once again, Michelle Belnavis, a cultural relevance instructional resource teacher (K-5) for MMSD, has organized an event that brings African American community leaders, families, staff, students, and neighborhood organizations together to provide inspiration and information to schools and neighborhoods in honor of National African American Parent Involvement Day."We have been doing a lot of research in looking at the effect of having parents' actively involved in their children's education and a big part is that relationship-building," Belnavis tells The Madison Times. "This gives an opportunity for teachers and families and parents to come together for the purpose of celebrating unity. I think a lot of times when parents come into school there's a feeling like, 'I don't really belong here' or 'My children go to school here but I don't really have a connection with the teacher.'

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

SOMETIMES it takes but a single pebble to start an avalanche. On January 21st Timothy Gowers, a mathematician at Cambridge University, wrote a blog post outlining the reasons for his longstanding boycott of research journals published by Elsevier. This firm, which is based in the Netherlands, owns more than 2,000 journals, including such top-ranking titles as Cell and the Lancet. However Dr Gowers, who won the Fields medal, mathematics's equivalent of a Nobel prize, in 1998, is not happy with it, and he hoped his post might embolden others to do something similar.It did. More than 2,700 researchers from around the world have so far signed an online pledge set up by Tyler Neylon, a fellow-mathematician who was inspired by Dr Gowers's post, promising not to submit their work to Elsevier's journals, or to referee or edit papers appearing in them. That number seems, to borrow a mathematical term, to be growing exponentially. If it really takes off, established academic publishers might find they have a revolution on their hands.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Are hardbound textbooks going the way of slide rules and typewriters in schools?Education Secretary Arne Duncan and Federal Communications Commission chairman Julius Genachowski on Wednesday challenged schools and companies to get digital textbooks in students' hands within five years. The Obama administration's push comes two weeks after Apple Inc. announced it would start to sell electronic versions of a few standard high-school books for use on its iPad tablet.

Digital books are viewed as a way to provide interactive learning, potentially save money and get updated material faster to students.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

For the second consecutive year, Washington, D.C. , is ranked as the most literate city in the country, according to an annual statistical survey to be released today.Here is the top 10 for 2011, as ranked by Central Connecticut State University President Jack Miller, based on data that includes number of bookstores, library resources, newspaper circulation and Internet resources:

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

MG Siegler in his latest TechCrunch article posits that although Apple's new iBooks strategy is admirable in its effort to fix problems in public high schools, that it's not realistic and that their market strategy should revolve around colleges and college textbooks.On the surface, which seems logical enough, his argument is sound. But It ignores the one, HUGE driving force in education: money.

Nearly all high schools are public, or receive public funding in one way or another and help to satisfy the law which states that students of high school age must attend school. Textbooks are merely a means of teaching these students topics which help these schools qualify for their funding.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Absent the glamour of the black mock turtleneck, Apple's Thursday event, held at the Guggenheim Museum in New York, still came bearing flowers of rhetoric, lovingly transplanted from their native soil in Cupertino's sunny clime. One such rhetorical staple, the feature checklist, made its appearance about nine minutes in. Usually, the checklist is used to contrast Apple's latest magical object with the feature set of lesser smartphones or other misbegotten tech tchotchkes; it was more than a little eye-popping to see the same rhetoric of invidious comparison used against the book in full -- that gadget which, as senior VP Phil Schiller reminded us, was invented (in its print incarnation) back at the end of the Hundred Years' War.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

On the heels of Apple's big education and iBooks event, it's worth taking a quick snapshot of the education publishing industry as it stands today.Not because the tools announced today will inevitably transform the future of education the way iTunes and the iPhone did the music and smartphone industries -- however fun that may be to imagine.

Rather, you simply can't understand Apple's interest in breaking into the education market without at least a little understanding of that market's scope. And you can't understand why Apple's adopted the approach that it has without understanding that market's connection to our wider media ecosystem.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Apple's controversial license terms are discussed here.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Apple is slated to announce the fruits of its labor on improving the use of technology in education at its special media event on Thursday, January 19. While speculation has so far centered on digital textbooks, sources close to the matter have confirmed to Ars that Apple will announce tools to help create interactive e-books--the "GarageBand for e-books," so to speak--and expand its current platform to distribute them to iPhone and iPad users.Along with the details we were able to gather from our sources, we also spoke to two experts in the field of digital publishing to get a clearer picture of the significance of what Apple is planning to announce.

So far, Apple has largely embraced the ePub 2 standard for its iBooks platform, though it has added a number of HTML5-based extensions to enable the inclusion of video and audio for some limited interaction. The recently-updated ePub 3 standard obviates the need for these proprietary extensions, which in some cases make iBook-formatted e-books incompatible with other e-reader platforms. Apple is expected to announce support for the ePub 3 standard for iBooks going forward.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Summary of the Wisconsin Read to Lead Task Force Recommendations, January, 2012Related: Erin Richards' summary (and Google News aggregation) and many SIS links.

Teacher Preparation and Professional Development

All teachers and administrators should receive more instruction in reading pedagogy that focuses on evidence-based practices and the five components of reading as defined by the National Reading Panel (phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension).

There must be more accountability at the state level and a commitment by institutions of higher education to improving teacher preparation.Licensure requirements should be strengthened to include the Massachusetts Foundations of Reading exam by 2013.

Teacher preparation programs should expand partnerships with local school districts and early childhood programs.

Information on the performance of graduates of teacher preparation programs should be available to the public.

A professional development conference should be convened for reading specialists and elementary school principals.

DPI should make high quality, science-based, online professional development in reading available to all teachers.

Professional development plans for all initial educators should include a component on instructional strategies for reading and writing.

Professional development in reading instruction should be required for all teachers whose students continually show low levels of achievement and/or growth in reading.

- Screening, Assessment, and Intervention

Wisconsin should use a universal statewide screening tool in pre-kindergarten through second grade to ensure that struggling readers are identified as early as possible.

Proper accommodations should be given to English language learners and special education students.Formal assessments should not replace informal assessments, and schools should assess for formative and summative purposes.

Educators should be given the knowledge to interpret assessments in a way that guides instruction.

Student data should be shared among early childhood programs, K-12 schools, teachers, parents, reading specialists, and administrators.

Wisconsin should explore the creation of a program similar to the Minnesota Reading Corps in 2013.

- Early Childhood

DPI and the Department of Children and Families should work together to share data, allowing for evaluation of early childhood practices.

All 4K programs should have an adequate literacy component.

DPI will update the Wisconsin Model Early Learning Standards to ensure accuracy and alignment with the Common Core State Standards, and place more emphasis on fidelity of implementation of the WMELS.

The YoungStar rating system for early childhood programs should include more specific early literacy criteria.

- Accountability

The Educator Effectiveness Design Team should consider reading outcomes in its evaluation systems.

The Wisconsin School Accountability Design Team should emphasize early reading proficiency as a key measure for schools and districts. Struggling schools and districts should be given ongoing quality professional development and required to implement scientific research-based screening, assessment, curriculum, and intervention.

Educators and administrators should receive training on best practices in order to provide effective instruction for struggling readers.

The state should enforce the federal definition for scientific research-based practices, encourage the use of What Works Clearinghouse, and facilitate communication about effective strategies.

In addition to effective intervention throughout the school year, Wisconsin should consider mandatory evidence-based summer school programs for struggling readers, especially in the lower grades, and hold the programs accountable for results.

- Family Involvement

Support should be given to programs such as Reach Out and Read that reach low-income families in settings that are well-attended by parents, provide books to low-income children, and encourage adults to read to children.The state should support programs that show families and caregivers how to foster oral language and reading skill development in children.

Adult literacy agencies and K-12 schools should collaborate at the community level so that parents can improve their own literacy skills.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

What inspired you to start The Concord Review?Diane Ravitch, an American historian of education, wrote a col- umn in The New York Times in 1985 about the ignorance of his- tory among 17-year-olds in the United States, based on a study of 7,000 students. As a history teacher myself at the time, I was interested to see that what concerned me was a national problem, and I began to think about these issues. It occurred to me that if I had one or two very good students writing his- tory papers for me and perhaps my colleagues had one or two, then in 20,000 United States high schools (and more overseas) there must be a large number of high school students doing exemplary history research papers. So in1987, I established The Concord Review to provide a journal for such good work in his- tory. I sent a four-page brochure calling for papers to every high school in the United States, 3,500 high schools in Canada, and 1,500 schools overseas. The papers started coming in, and in the fall of 1988, I was able to publish the first issue of The Concord Review. Since then, we have published 89 issues.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

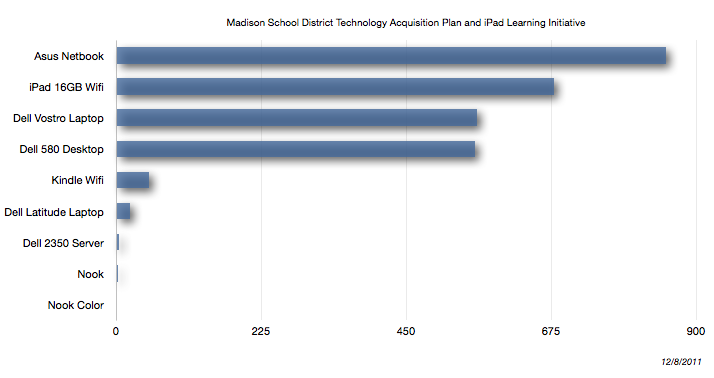

Bill Smojver, Director of Technical Services:

Madison Metropolitan School District was provided an award from the Microsoft Cy Pres settlement in the Fall of 2009. Since that time the district has utilized many of these funds to prorate projects across the district in order to free up budgeted funds and to provide for more flexibility. The plan and process for these funds liquidates the General Purpose portion of the Microsoft Cy Pres funds, provides an equitable allocation per pupil to each school, and is aimed at increasing the amount of technology within our schools.I found the device distribution to be quite interesting. The iPad revolution is well underway. Technology's role in schools continues to be a worthwhile discussion topic.The total allocation remaining from Cy Pres revenues totals $2,755,463.11, which was the target for the technology acquisition plan. Two things happened prior to allocating funds to schools: first was to hold back $442,000 for the future purchase of iPads for our schools (at $479 per iPad this equates to a 923 iPads), and second was to hold back $200,000 necessary for increased server capacity to deal with the increase in different types of technology.

The final step was to allocate the remaining funding ($2,113,463.11) out to the schools on a per pupil basis. This was calculated at $85.09 per pupil across all schools within the district.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Fellow members of the Electronic Educational Entertainment Association. My remarks will be brief, as I realize you all have texts to read, messages to tweet, and you will of course want to take photos of those around you to post on your blog.

I only want to remind you that the book is our enemy. Every minute a student spends reading a book is time taken away from purchasing and using the software and hardware the sale of which we depend on for our livelihoods.

You should keep in mind the story C.S. Lewis told of Wormwood, the sales rep for his uncle Screwtape, a district manager Below, who was panicked when his target client joined a church. What was he to do? Did this mean a lost account? Screwtape reassured him with a story from his own early days. One of his accounts went into a library, and Screwtape was not worried, but then the client picked up a book and began reading. However, then he began to think! And, in an instant, the Enemy Above was at his elbow. But Screwtape did not panic--fortunately it was lunchtime, and he managed to get his prospect up and at the door of the library. There was traffic and busyiness, and the client thought to himself, "This is real life!" And Screwtape was able to close the account.

In the early days, Progressive Educators would sometimes say to students, in effect, "step away from those books and no one gets hurt!" because they wanted students to put down their books, go out, work for social justice, and otherwise take part in "real life" rather than get into those dangerous books and start thinking for themselves, for goodness' sake!

But now we have more effective means of keeping our children in school and at home away from those books. We have Grand Theft Auto and hundreds of other games for them to play at escaping all moral codes. We have smartphones, with which they can while away the hours and the days texting and talking about themselves with their friends.

We even have "educational software" and lots of gear, like video recorders, so that students can maintain their focus on themselves, and stay away from the risks posed by books, which could very possibly lead them to think about something besides themselves. And remember, people who read books and think about something besides themselves do not make good customers. And more than anything, we want and need good customers, young people who buy our hardware and software, and who can be encouraged to stay away from the books in libraries, which are not only free, for goodness's sake, but may even lead them to think. And that will be no help at all to our bottom line. Andrew Carnegie may have been a philanthropist, but by providing free libraries he did nothing to help us sell electronic entertainment products. We must never let down our guard or reduce our advertising. Just remember every young person reading a book is a lost customer! Verbum Sap.

-----------------------------

"Teach by Example"

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

www.tcr.org/blog

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Sometimes you find yourself part of a trend accidentally: Some old, beloved jacket in your closet becomes fashionable, or your private, favorite novel is discovered by the world. Having written four books of fiction for adults, I wrote a novel for kids, and looked up from the first draft to find that other writers were doing the same thing--and adults were reading the books.My plunge into the world of children's publishing surprised my friends as much as it surprised me. One asked, "How did you make the change? Did you have some kind of magical elixir?" I did, if you consider that magical elixirs are slow and difficult and sometimes frustrating to make, and involve wrong turns and unexpected discoveries. But here's the basic recipe:

1. Don't worry about what category the book belongs in. I thought I was writing a young adult novel and discovered that there was a type of book called "middle reader" only when my publishers told me I'd written one. I worked in a state of utter naïveté about what the rules are for writing children's books, which was liberating.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

The Royal Society continues to support scientific discovery by allowing free access to more than 250 years of leading research.From October 2011, our world-famous journal archive - comprising more than 69,000 articles - will be opened up and all articles more than 70 years old will be made permanently free to access.

kite

The Royal Society is the world's oldest scientific publisher and, as such, our archive is the most comprehensive in science. Treasures in the archive include Isaac Newton's first published scientific paper, geological work by a young Charles Darwin, and Benjamin Franklin's celebrated account of his electrical kite experiment. Readers willing to delve a little deeper may find some undiscovered gems from the dawn of the scientific revolution - including Robert Boyle's account of monstrous calves, grisly tales of students being struck by lightning, and early experiments on to how to cool drinks 'without the Help of Snow, Ice, Haile, Wind or Niter, and That at Any Time of the Year.'

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

The first edition of this book appeared in 1946. Eight translations were made of it, and there were numerous paperback editions. In a paperback of 1961, a new chapter was added on rent control, which had not been specifically considered in the first edition apart from government price-fixing in general. A few statistics and illustrative references were brought up to date.Otherwise no changes were made until now. The chief reason was that they were not thought necessary. My book was written to emphasize general economic principles, and the penalties of ignoring them-not the harm done by any specific piece of legislation. While my illustrations were based mainly on American experience, the kind of government interventions I deplored had become so internationalized that I seemed to many foreign readers to be particularly describing the economic policies of their own countries.

Nevertheless, the passage of thirty-two years now seems to me to call for extensive revision. In addition to bringing all illustrations and statistics up to date, I have written an entirely new chapter on rent control; the 1961 discussion now seems inadequate. And I have added a new final chapter, "The Lesson After Thirty Years," to show why that lesson is today more desperately needed than ever.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

"The next twenty-five years offer an opportunity to transform the way students have learned for centuries. We will be able to deliver education to students where they are, based on their specific needs, desires, and backgrounds."--Andrew S. RosenImagine a university where programs are tailored to the needs of each student, the best professors are available to everyone, curriculum is relevant to the workplace - and the value of the education is demonstrable. In Change.edu, Andrew S. Rosen shows how that future is possible but in danger of being stifled by a system of incentives that emphasize prestige and tradition, rather than access and outcomes.

The U.S. higher education system has historically been considered one of the best in the world. This thought-provoking story presents the imperative for transforming that system for the 21st century and beyond. Rosen takes on the sacred cows of traditional higher education models, and calls on the country to demand the changes we need to build a qualified workforce and compete in a global economy. Change.edu is sure to open minds -- and open doors to a wealth of opportunities.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

AMONG the episodes in his life that didn't last, that were over almost before they began, including a spell in the army and a try at marriage, Michael Hart was a street musician in San Francisco. He made no money at it, but then he never bought into the money system much--garage-sale T-shirts, canned beans for supper, were his sort of thing. He gave the music away for nothing because he believed it should be as freely available as the air you breathed, or as the wild blackberries and raspberries he used to gorge on, growing up, in the woods near Tacoma in Washington state. All good things should be abundant, and they should be free.Project Gutenberg:He came to apply that principle to books, too. Everyone should have access to the great works of the world, whether heavy (Shakespeare, "Moby-Dick", pi to 1m places), or light (Peter Pan, Sherlock Holmes, the "Kama Sutra"). Everyone should have a free library of their own, the whole Library of Congress if they wanted, or some esoteric little subset; he liked Romanian poetry himself, and Herman Hesse's "Siddhartha". The joy of e-books, which he invented, was that anyone could read those books anywhere, free, on any device, and every text could be replicated millions of times over. He dreamed that by 2021 he would have provided a million e-books each, a petabyte of information that could probably be held in one hand, to a billion people all over the globe--a quadrillion books, just given away. As powerful as the Bomb, but beneficial.

Project Gutenberg offers over 36,000 free ebooks to download to your PC, Kindle, Android, iOS or other portable device. Choose between ePub, Kindle, HTML and simple text formats.We carry high quality ebooks: All our ebooks were previously published by bona fide publishers. We digitized and diligently proofed them with the help of thousands of volunteers.

No fee or registration is required, but if you find Project Gutenberg useful, we kindly ask you to donate a small amount so we can buy and digitize more books. Other ways to help include digitizing more books, recording audio books, or reporting errors.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Emma Brown, via a kind James Dias email:

Seventh-grade history teacher Mark Stevens bellowed a set of 21st-century instructions as students streamed into class one recent Friday at Fairfax County's Glasgow Middle School."Get a computer, please! Log on," he said, "and go to your textbook."

Electronic books, having changed the way many people read for pleasure, are now seeping into schools. Starting this fall, almost all Fairfax middle and high school students began using online books in social studies, jettisoning the tomes that have weighed down backpacks for decades.

It is the Washington area's most extensive foray into online textbooks, putting Fairfax at the leading edge of a digital movement that publishers and educators say inevitably will sweep schools nationwide.

But questions remain about whether the least-privileged children will have equal access to required texts. Many don't have computers at home, or reliable Internet service, and the school system is not giving a laptop or e-reader to every student.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Business schools are under the microscope again, their relevance and value questioned in many quarters. The financial crisis has triggered a self-examination of their raison d'etre.However, before we can decide whether and how business schools need to change, it is worth pausing to consider how and why business schools have evolved as they have.

A new book, "The Roots, Rituals and Rhetorics of Change: North American Business Schools After the Second World War," describes the revolution in business education that took place in the 1950s and 1960s. The book was published by Stanford University Press.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

In honor of the National Book Festival, running Sept. 24 - 25 on the National Mall, we asked some of the authors participating to share their thoughts on a few writerly subjects.What do writers think about writing? Here's a small selection of what they had to say.

THE THING I'M HAPPIEST ABOUT IN MY WRITING CAREER IS . . .

That rarest of occurrences: being able to finance my writing life with the writing itself.

-- Russell Banks

The sound of my father's voice on the telephone when I told him that I had been awarded the Pulitzer Prize. That the book, "Thomas and Beulah," dealt with my home town and was about my maternal grandparents made the announcement that much sweeter.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

When I read "Library Limbo," a news story about library staff members being laid off the University of San Diego, I had to resist adding a comment because I needed what preschools sometimes call a "time out." My first responses were strong, but not measured, and in stories like this there are always layers of complexity that the best journalist in the world cannot represent. Rarely are personnel decisions of any kind easy to describe, and some of the key information is usually not publicly available. Often what is described as the elimination of a position becomes suddenly not discussable because it's a personnel matter. A personnel matter that can't be discussed is not about a change in a position but about the performance of the person in the position, which is a different . . . hang on, I apparently need to go sit quietly in the corner for a few more minutes . . .Okay. So let's not talk about that particular situation at the University of San Diego because I don't know enough about it to comment meaningfully. Instead I want to propose a few general things about libraries, change, and organizations.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Just as many predicted, sales figures show that more people are opting to buy e-books rather than printed copies. Sales of e-books rose 167 percent in June, reports Publishers Weekly, with sales totaling $473.8 million for the first half of the year. But sales of print books -- both paperbacks and hardcovers -- continue to decline.It isn't just publishers that are scrambling to adjust their business models to the growing demand for e-books; so too are libraries having to reconsider how they will provide content for their patrons.

Even though there's keen interest on the part of library patrons to check out e-books, making a move to digital loans is not going to be easy. That's true for all libraries, but it's especially true for school libraries, many of which already face budget woes, and as such, have to weigh carefully how to invest in new books to stock the shelves.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

THOMAS NAGEL, an American philosopher, wants to know what it is like for a bat to be a bat. Ian Anderson, a Scot who performs with the band Jethro Tull, sang of a slightly less intractable difficulty: "wise men don't know how it feels to be thick as a brick." In "School Blues" Daniel Pennac, a prize-winning French writer, describes what faces a school dunce when the teacher before him cannot recall what it felt like to be ignorant.Mr Pennac was once such a child (he uses the French cancre, as in Cancer, the crab: a creature that scuttles sideways instead of advancing forwards). But despite becoming a teacher, he can remember what it was like not to understand lessons. The voices in his head remind him of it. They taunt him throughout his semi-autobiographical novel, which partially traces his sorry academic career as the child of high-achieving parents whose three older brothers excelled at school. Luckily for him, his parents did not let him flee the system but instead persisted in finding a teacher who would help him to succeed. The breakthrough came aged 14 when his latest tutor--"no doubt amazed by my increasingly inventive excuses as to why I hadn't done my homework"--commissioned him to write essays and then a novel.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Daniel Loxton via a kind Larry Winkler email:

Evolution: How We and All Living Things Came to Be took home the national Lane Anderson Award as the best Canadian science book for young readers at an award dinner in Toronto last night. The win was reported today by the National Post, the Vancouver Sun, Quill & Quire, the Canadian Children's Book Center and other media. It was published by Canadian publisher Kids Can Press. But it's not for lack of trying that a Canadian publisher rather than American publisher issued this book.According to author Daniel Loxton, US publishers wouldn't touch it.

"It's important to realize that most of the publishing professionals I dealt with in the US were lovely and encouraging. They all said "no," but some recommended smaller, artier presses they felt might consider Evolution.... [S]ome of America's top children's publishing professionals rejected Evolution, some citing concerns that it was too controversial, too much of "a tough sell," or ("in today's climate") too likely to find needed distribution channels closed.... It was certainly frustrating to knock on cold doors, but I am sympathetic to publishers. [I]t's a tough time for book producers, and they need to work hard to mitigate risk. Publishers face the on the ground reality that almost half of American adults--many of them reviewers, librarians, booksellers, or teachers--believe that evolution did not happen at all.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

there's been a lot going on recently with books. i've been watching eric ries and i'm blown away by how successful he's been at promoting his book the lean startup. i saw that @dharmesh wrote about it at onstartups.com, and tweeting out small agreeable little tidbits from the book is genius--i don't know whether this was intentional or not, but that's an awesome idea.i met noah kagan last friday to catch up over drinks at showdown in sf, and i met someone interesting there: laura roeder. i usually meet people who claim to be "social media experts" (as every hacker reading this rolls their eyes) but this woman actually had a significant following and presence on twitter and facebook, and not one of those fake "follow me and i'll auto-follow you back" type of things. i dropped in on a small video conference she was doing today corresponding to her book launch, which i had not realized she was working on (for some reason, she didn't mention it when we met, even though i had mentioned startups open sourced was paying my rent at this point).

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

As noted in a previous entry ('Visualizing the globalization of higher education and research'), we've been keen to both develop and promote high quality visualizations associated with the globalization of higher education and research. On this note, the wonderful Floating Sheep collective recently informed me about some new graphics that will be published in:Graham, M., Hale, S. A., and Stephens, M. (2011) Geographies of the World's Knowledge, London, Convoco! Edition.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

April 16 is the 50th anniversary of the publication of a little book that is loved and admired throughout American academe. Celebrations, readings, and toasts are being held, and a commemorative edition has been released.I won't be celebrating.

The Elements of Style does not deserve the enormous esteem in which it is held by American college graduates. Its advice ranges from limp platitudes to inconsistent nonsense. Its enormous influence has not improved American students' grasp of English grammar; it has significantly degraded it.

The authors won't be hurt by these critical remarks. They are long dead. William Strunk was a professor of English at Cornell about a hundred years ago, and E.B. White, later the much-admired author of Charlotte's Web, took English with him in 1919, purchasing as a required text the first edition, which Strunk had published privately. After Strunk's death, White published a New Yorker article reminiscing about him and was asked by Macmillan to revise and expand Elements for commercial publication. It took off like a rocket (in 1959) and has sold millions.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Nature Publishing Group, which publishes several highly regarded scientific journals and textbooks, was founded in England in 1869, eight years before electric lights illuminated the streets of London. Now, 140 years later, with the help of Harvard Classics scholar Vikram Savkar, the company is beginning to disrupt the traditional textbook model that it helped to create. This month at California State University, the company released Principles of Biology, an interactive, constantly updating biology textbook that retails for less than $50. Like most digital textbooks, the software is accessible on laptops and tablets, but unlike most digital textbooks, it's not just a scan of a .pdf. The company calls it a "digital reinvention of the textbook," meaning that students can interact with the material; they can literally match amino acids and corresponding DNA with their fingers. Inc.com's Eric Markowitz spoke with Vikram Savkar about what it takes to create a culture of innovation in an old-school company.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

A group of business and philanthropic leaders appointed by Governor Dannel P. Malloy presented their education reform proposals to the state Board of Education Wednesday, pitching changes to teacher certification requirements, preparation programs and evaluations to help close Connecticut's dramatic achievement gap.Members of the Connecticut Council on Education Reform said they considered the timing appropriate, coming as Malloy introduced his new education commissioner and reiterated that education will be a priority in next year's legislative session.

"We think next year could be the lynchpin," said Steve Simmons, vice chair of the council and CEO of Simmons/Patriot Media and Communications. "The governor has said that this first year was focused on the budget crisis and the second year was going to be education reform. I think we have a great chance here over this next nine or ten month period to really push for change."

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

While they say that all politics is local, Colorado seems to be national news, yet again. Our state is featured prominently in Steven Brill's new book, Class Warfare, which is receiving a lot of press from national news outlets.Weaving a narrative around the passage of Senate Bill 10-191 in Colorado, Brill tells a good story, replete with heroic figures like Senator Mike Johnston. I worked closely on SB 191 from its inception to passage, I can tell you that the on the ground details of its success are even more interesting than what's depicted in Brill's account.

Please see DFER's case study on SB 191 here for a close examination of the strategy, the broad coalition, and the bipartisan champions that helped make SB 191 a reality. Without the active support of the sophisticated coalition of political leaders on both sides of the aisle, including House sponsors Rep. Christine Scanlan and Rep. Carole Murray, non-profit organizations such as Stand for Children Colorado, civil rights groups, and business leaders that worked with the media, spoke with legislators, and reached out to their communities, the bill would not have passed. For further reading, Van Schoales, a DFER-CO Advisory Committee member, has written a review of Class Warfare: available here.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Nicolaus Copernicus, the man credited with turning our perception of the cosmos inside out, was born in the city of Torun, part of "Old Prussia" in the Kingdom of Poland, at 4:48 on Friday afternoon, February 19 1473. By the time his horoscope for that auspicious moment was created - at the end of the astronomer's life - his contemporaries already knew that he had fathered an alternative universe: that he had defied common sense and received wisdom to place the Sun at the centre of the heavens, then set the Earth in motion around it.Copernicus grew up Niklas Koppernigk, the second son and youngest of four children of a merchant family. He was raised in Torun, in a tall brick house that is now a museum to the memory of the town's famous son. From here, he and his brother, Andrei, could walk to classes at the parish school of St. John's Church or to the family warehouse near the river Vistula. When Niklas was 10, his father died, and he and his siblings came under the care of their maternal uncle, Lukasz Watzenrode, a minor cleric, or "canon", in a nearby diocese. He arranged a marriage contract for one niece and consigned the other to a convent, but his nephews he supported at school, until they were ready to attend his alma mater, the Jagiellonian University in Krakow. By then, Uncle Lukasz had risen to become Bishop of Varmia.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

The beginning of a freshman's college experience is an exciting time. Dining halls! No bedtime! Taunting your RA! Exorbitantly expensive textbooks!

Wait, that last one is no fun at all. It's hard to make that first trip to the college bookstore for required texts without leaving with a bit of sticker shock. Why are textbooks so astonishingly expensive? Let's take a look.Publishers would explain that textbooks are really expensive to make. Dropping over a hundred bucks for a textbook seems like an outrage when you're used to shelling out $10 or $25 for a novel, but textbooks aren't made on the same budget. Those hundreds of glossy colorful pages, complete with charts, graphs, and illustrations, cost more than putting black words on regular old white paper. The National Association of College Stores has said that roughly 33 cents of every textbook dollar goes to this sort of production cost, with another 11.8 cents of every dollar going to author royalties. Making a textbook isn't cheap.

There's certainly some validity to this explanation. Yes, those charts and diagrams are expensive to produce, and the relatively small print runs of textbooks keep publishers from enjoying the kind of economies of scale they get on a bestselling popular novel. Any economist who has a pulse (and probably some who don't) could poke holes in this argument pretty quickly, though.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

That's the title of a post from Heather Mac Donald (Secular Right); here's an excerpt, though you should read the whole post:In the course of a column blasting media entrepreneur Steven Brill's new book on the school reform movement, New York Times reporter Michael Winerip inadvertently sets out his economic assumptions. A revelation of an entire world view does not get any more crystalline than this. (Regarding education, Winerip almost equally tellingly criticises Brill for not showing enough respect to teachers and teachers unions.)Winerip lists several of Brill's sources -- the "millionaires and billionaires who attack the unions and steered the Democratic Party to their cause" -- then adds:

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

For many students and their families, scraping together the money to pay for college is a big enough hurdle on its own. But a new survey has found that, once on a campus, many students are unwilling or unable to come up with more money to buy books--one of the very things that helps turn tuition dollars into academic success.In the survey, released on Tuesday by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group, a nonprofit consumer-advocacy organization, seven in 10 college students said they had not purchased a textbook at least once because they had found the price too high. Many more respondents said they had purchased a book whose price was driven up by common textbook-publishing practices, such as frequent new editions or bundling with other products.

"Students recognize that textbooks are essential to their education but have been pushed to the breaking point by skyrocketing costs," said Rich Williams, a higher-education advocate with the group, known as U.S. PIRG. "The alarming result of this survey underscores the urgent need for affordable solutions."

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

If you're looking for a textbook example of technology obstruction by the media industry, look no further than e-textbooks.Related: e-textbook readers compared."About 90 percent of the time, the cheapest option is still to buy a used book and then resell that book," says Jonathan Robinson, founder of FreeTextbooks.com, an online retailer of discount books. "That is really an obstacle for widespread adoption [of e-textbooks], because smarter consumers realize that and are not going to leap into the digital movement until the pricing evens out."

That's sad news for students headed back to college this fall. IPads, Kindles and even HP's doomed TouchPad tablet are literally flying off the shelves, and many students wouldn't be caught dead on campus without one.

Meanwhile, e-textbook sales at the nation's universities are stuck in single digits, with little hope of escape before 2013. According to Simba Information , in the next two years e-textbook revenue will reach just $585.4 million and account for just over 11 percent of all higher education and career-oriented textbook sales -- a notable but not yet predominant force in the marketplace.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Textbook pirates have struck again. Nearly three years after publishers shut down a large Web site devoted to illegally trading e-textbooks, a copycat site has sprung up--with its leaders arguing that it is operating overseas in a way that will be more difficult to stop.The new site, LibraryPirate, quietly started operating last year, but it began a public-relations blitz last week, sending letters to the editor to several news sites, including The Chronicle, in which it called on students to make digital scans of their printed textbooks and post them to the site for free online.

Such online trading violates copyright law, but some people have apparently been adding pirated versions of e-textbooks to the site's directory. The site now boasts 1,700 textbooks, organized and searchable. Downloading the textbooks requires a peer-to-peer system called BitTorrent, and the LibraryPirate site hosts a step-by-step guide to using it.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Apply. Visit campus. Complete the financial aid form. Get four years of free textbooks.First-year University of Dayton students can receive up to $4,000 over four years for textbooks by completing three steps of the fall 2012 application process by March 1.

"We want to help parents and students understand that from the very first day, a University of Dayton education is very rewarding," said Kathy McEuen Harmon, assistant vice president and dean of admission and financial aid.

"Through this initiative, we want to underscore that a University of Dayton education is affordable and we are committed to helping families in very tangible ways," she said.

With the economy still difficult, Harmon said the free textbook program will bring families clarity and certainty about one piece of the financial puzzle.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Leadership in any organization comes from the top. No, the superintendent is not "the top" of a school district organization. The top spot is held by the School Board, seven elected individuals who work together to implement policies and practices to meet the changing needs of students and families, all within the limited resources, financial and otherwise, that are available.I have been fortunate during my first two years as superintendent to work with a dedicated and hard-working School Board. Being a board member requires the commitment of endless hours of time and effort, and is frequently somewhat thankless as there are very few decisions made in a large school district that will be welcomed by all. The service and support of our current board is appreciated.

Recently the School Board met in a retreat to review the best practices of high-performing boards and evaluate what changes they can implement to improve not only the functioning of the School Board, but ultimately the effectiveness and efficiency of the school district. I commend our board for this undertaking as it is a great modeling and example of the culture we are seeking to develop in the South Washington County Schools of continuous improvement and performance excellence. While the School Board generally functions very well, there is always room for improvement and this board is committed to such evaluation, assessment and improvement of their performance.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Akademos, Inc., a leading provider of integrated online bookstores and marketplaces to educational institutions, announced today that it has launched a digital reader that will allow its member institutions to access electronic content from traditional publishers and from open resources, such as the Connexions Consortium, World Public Library, the Guttenberg Project, and many others.The company also announced its first major Open Educational Resources (OER) partnership with publisher Flat World Knowledge, which is providing the company with its full catalog of over 40 high-quality textbooks covering major subject areas for introductory general education colleges courses.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

WHEN school textbooks make the headlines in East Asia, they are usually cast as bystanders to some intractable old dispute, and related demands that children be taught "correct" history. Thankfully though, future-minded officials in South Korea have given cause for this correspondent to write about something altogether different: by 2015, all of the country's dead-tree textbooks will be phased out, in favour of learning materials carried on tablet computers and other devices.The cost of setting up the network will be $2.1 billion. It is hoped that cutting out printing costs will go some way towards compensating for this expenditure. Environmentalists will of course be pleased, regardless. A cloud network will be set up to host digital copies of all existing textbooks, and to give students the (possibly unwelcome) ability to access materials at any time, via iPads, smartphones, netbooks, and even Stone-Age PCs. Kids will need to come up with a new range of excuses for not doing their homework: the family dog cannot be blamed for eating a computer, nor can a file hosted on a cloud network be left behind on a bus.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Alice Wong considered herself an avid reader, but it didn't occur to her that she might have to learn how to read to her two young children. She was even less aware that courses were available to teach this skill."I never used to understand the power of reading," says Wong, who has a four-year-old son and a two-year-old daughter.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

In today's Academic Minute, the University of North Florida's Katie Monnin describes how the use of graphic novels in the classroom can improve reading comprehension and attitudes about reading among young readers. Monnin is an assistant professor of literacy at North Florida and author of the forthcoming Really Reading with Graphic Novels and Teaching Content Area Graphic Novels.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Well, that oversized Kindle didn't become the textbook killer Amazon hoped it would be, but at least one country is moving forward with plans to lighten the load on its future generation of Samsung execs. South Korea announced this week that it plans to spend over $2 billion developing digital textbooks, replacing paper in all of its schools by 2015. Students would access paper-free learning materials from a cloud-based system, supplementing traditional content with multimedia on school-supplied tablets. The system would also enable homebound students to catch up on work remotely -- they won't be practicing taekwondo on a virtual mat, but could participate in math or reading lessons while away from school, for example. Both programs clearly offer significant advantages for the country's education system, but don't expect to see a similar solution pop up closer to home -- with the US population numbering six times that of our ally in the Far East, many of our future leaders could be carrying paper for a long time to come.Brian S. Hall has more.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Secretary for Education Michael Suen Ming-yeung yesterday threw down the gauntlet to school textbook publishers, saying the government would take over publishing them unless "monopolies" get serious about selling the books and teaching materials separately.Advocacy groups welcomed the idea, saying it would lower prices, but publishers described the one-year ultimatum as "mission impossible".

Publishers last year pledged to separately sell textbooks and teaching materials, which can cost twice as much as the textbooks. But they recently said it would take another three years to do so.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Literary agent Andrew Wylie is of the old school. His office suite in New York's Fisk Building feels more like a faculty lounge than a synergistic, new-media conglomerate. But the Wylie Agency, which represents some 750 clients, including a who's who of the literary establishment--Roth, Updike, Rushdie--has been at the vanguard of changes in the book industry world-wide. With the advent of e-books and the demise of Borders, the publishing establishment may seem to be crumbling. Yet Wylie, renowned for his ability to extract huge advances from tightfisted publishers, doesn't seem to be much ruffled.Nicknamed "The Jackal" for his aggressive deal-making, Wylie struck terror into publishers last year by setting up a company, Odyssey Editions, to distribute electronic versions of books he represents through Amazon.com. But don't mistake him for a pop-culture version of a vulpine 15-percenter. Trim, polite and circumspect, Wylie, 63, is uncaffeinated. A New England WASP, he stands foursquare for literary elitism and good old-fashioned standards. And while he has his share of celebrity and political clients, he insists his work is all about great, lasting literature, not quick-buck synergies, "60 Minutes" tie-ins or Facebook friends.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

With few exceptions, Americans spend more on public education than anyone else in the world, but we get some of the worst results. The reason is that most of our public education systems do not properly teach students what they need to know.That's it. There is no magic. And the federal takeovers, the jazzy new technology, Bill Gates' money, the data-gathering, reform, transformation, national initiatives, removal of teacher seniority, blaming of parents, hand-wringing in the media, and budget shifting won't change that simple fact.

In all of the local, state and federal plans for reforming and transforming public education, I see the bureaucracy growing, the taxpayer bill exploding, the people's voice being eliminated, good teachers being threatened with firing or public humiliation, and students not being taught what they need to know.

A May 25 Wall Street Journal article says some schools now charge parents fees for basic academics, as well as for extracurricular activities, graded electives and advanced classes. Those are private-school fees for a public-school education, and that's just wrong.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-Being. By Martin Seligman. Free Press; 368 pages; $26. Nicholas Brealey PublishingThe idea that it is the business of governments to cheer up their citizens has moved in recent years to centre-stage. Academics interested in measures of GDH (gross domestic happiness) were once forced to turn to the esoteric example of Bhutan. Now Britain's Conservative-led government is compiling a national happiness index, and Nicolas Sarkozy, France's president, wants to replace the traditional GDP count with a measure that takes in subjective happiness levels and environmental sustainability.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Just in time for the summer reading season, Amazon.com announced its list of the Top 20 Most Well-Read Cities in America. After compiling sales data of all book, magazine and newspaper sales in both print and Kindle format since Jan. 1, 2011, on a per capita basis in cities with more than 100,000 residents, the Top 20 Most Well-Read Cities are:

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

A hard-hitting look inside America's K-12 showing why children are failing, who is standing in their way, who is helping, and what needs to happen.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Politicians are usually sticks in the mud, technologywise, but that certainly wasn't the case down in Tallahassee this week. Florida legislators closed their eyes, clicked their heals, and took a giant leap forward into the Information Age, passing a budget measure that bans printed textbooks from schools starting in the 2015-16 school year. That's right: four years from now it will be against the law to give a kid a printed book in a Florida school. One lawmaker said the bill was intended to "meet the students where they are in their learning styles," which means nothing but sounds warm and fuzzy.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Rob Harris, via a kind reader's email:

Two new children's books explore the life of Jane Goodall, the chimpanzee expert and prominent conservationist. The Times spoke with Dr. Goodall about living out her childhood dreams.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Perry and Lester are two guys living in an abandoned mall outside of Miami. They're the sort of guys who, to borrow a phrase from the Queen in Alice in Wonderland, can think up six impossible things before breakfast -- and then build them in their workshop out of stuff they've found in the junkyard.In short, they're makers.

Cory Doctorow's Makers: A Novel of the Whirlwind Changes to Come is jam-packed with cool ideas. In the book, a lot of these come from Perry and Lester, like a toast-making robot made of seashells or the Distributed Boogie Woogie Elmo Motor Vehicle Operation Cluster, which uses a gaggle of discarded toys to drive a Smart car via voice commands. Now these two examples are pretty silly -- something you do just to prove you can, but there's also some stuff that shows up later in the book that made me think, "Hey, I'd buy one of those!" Parts of the book read like a "Best of Kickstarter" highlights reel.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Barney Jopson and David Gelles:

Amazon will let users of its Kindle e-reader borrow electronic books from two-thirds of US libraries as it seeks to broaden the device's appeal in the face of competition from Apple's iPad and rival tablets.The world's largest online retailer said that from later this year, customers would be able to borrow e-books from libraries and read - and annotate - them on a Kindle or any other device to which users have downloaded a Kindle app.

Amazon's move intensifies questions about the commercial threat the growing popularity of e-readers poses to traditional book publishers, which have acknowledged a concern that e-book lending might cannibalise sales of books. US public libraries have spent several years building up their e-book collections, which have been accessible to users of Barnes & Noble's Nook and Sony's Reader device. But until now they have not worked with the Kindle.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

First there was Amy Chua, the Yale law professor and author of "Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother," who sent legions of parents into a tizzy with her exacting standards for piano practice and prohibitions against sleepovers.Now comes Bryan Caplan, an economist at George Mason University whose book "Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids: Why Being a Great Parent is Less Work and More Fun Than You Think" was published on Tuesday. In it, he argues that parenting hardly matters, and that we should just let our children watch more television and play video games. With parenting made so easy, he says, we should go ahead and have more children.

It's the age-old nature-or-nurture debate. Ms. Chua clearly favors the nurture side of the equation (if her heavy-handed approach could be described as "nurturing"). Mr. Caplan, who has already been dubbed the "Un-Tiger Mom," writes, "While healthy, smart, happy, successful, virtuous parents tend to have matching offspring, the reason is largely nature, not nurture."

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

I am probably the nation's most devoted reader of real-life high school reform drama, an overlooked literary genre. If there were a Pulitzer Prize in this category, Alexander Russo's new book on the remaking of Locke High in Los Angeles would win. It is a must-read, nerve-jangling thrill ride, at least for those of us who love tales of teachers and students.Readers obsessed with fixing our failing urban schools will learn much from the personal clashes and political twists involved in the effort to save what some people called America's worst school. I remember the many news stories about Locke, and enjoyed discovering the real story was different, and more interesting.

Locke was not really our toughest high school. Russo finds some nice students and kind teachers. But its inner-city blend of occasional mayhem and very low test scores made it famous when its teachers revolted and helped turn it over to a charter school organization that tried to fix it by breaking it into smaller, more manageable pieces.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

On exam day in Sabina Trombetta's Colorado Springs first-grade art class, the 6-year-olds were shown a slide of Picasso's "Weeping Woman," a 1937 cubist portrait of the artist's lover, Dora Maar, with tears streaming down her face. It is painted in vibrant -- almost neon -- greens, bluish purples, and yellows. Explaining the painting, Picasso once said, "Women are suffering machines."The Economist has more.The test asked the first-graders to look at "Weeping Woman" and "write three colors Picasso used to show feeling or emotion." (Acceptable answers: blue, green, purple, and yellow.) Another question asked, "In each box below, draw three different shapes that Picasso used to show feeling or emotion." (Acceptable drawings: triangles, ovals, and rectangles.) A separate section of the exam asked students to write a full paragraph about a Matisse painting.

Trombetta, 38, a 10-year teaching veteran and winner of distinguished teaching awards from both her school district, Harrison District 2, and Pikes Peak County, would have rather been handing out glue sticks and finger paints. The kids would have preferred that, too. But the test wasn't really about them. It was about their teacher.

Trombetta and her students, 87 percent of whom come from poor families, are part of one of the most aggressive education-reform experiments in the country: a soon-to-be state-mandated attempt to evaluate all teachers -- even those in art, music, and physical education -- according to how much they "grow" student achievement. In order to assess Trombetta, the district will require her Chamberlin Elementary School first-graders to sit for seven pencil-and-paper tests in art this school year. To prepare them for those exams, Trombetta lectures her students on art elements such as color, line, and shape -- bullet points on Colorado's new fine-art curriculum standards.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Two Chinese novelists, Su Tong and Wang Anyi, have just been named finalists for the biennial Man Booker International Prize, the first Chinese writers to receive this honour. This is, therefore, something of a milestone. Yet, even while savouring the reflected glow of this accolade, those familiar with contemporary Chinese literature might wonder why it has taken so long. One explanation might be that this prize, like many international prizes, is based on works in English, and the English-language publishing world has been slow to produce Chinese novels or, indeed, much of anything in translation (a situation that, fortunately, seems to be improving somewhat).This particular prize, furthermore, is awarded not for a single book, but for a writer's entire corpus. China's recent history has been such that it has not been possible for a long time to publish novels; these two authors are, by the standards of such lifetime prizes, relatively young, Su Tong particularly so.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Reviewed by Katharine Beals, via a kind reader's email:

The Death and Life of the Great American School System was wildly hailed as author and education critic Diane Ravitch's dramatic about-face on No Child Left Behind, charter schools, and school choice. What's missing from this sensational take is that Ravitch has changed her mind only about school reform tactics, and not about what constitutes good schools, or about her top priorities in fostering them.

She still stresses curriculum--apparently still her topmost priority. She still supports a challenging, content-rich core curriculum of the sort promoted by E.D. Hirsch and his Core Knowledge Foundation. She still believes that the best teachers are those with who know their fields well and are enthusiastic about teaching. She still believes that attracting such teachers is nearly as essential, if not as essential, as curriculum reform.

It's in the question of why we've strayed so far from these ideals that Ravitch has shifted. While her earlier research (c.f. Left Back, published in 2000) critiqued, inter alia, a variety of prominent fad-peddling members of the education establishment, Ravitch now appears to blame just three factors: the high-stakes testing and accountability of No Child Left Behind (NCLB); the meddling in education by powerful outsiders like politicians and businessmen; and school choice ventures that skim off the best students and leave the rest to the most struggling of public schools.

On NCLB testing and accountability, Ravitch is convincing. Tests can be effective, comprehensive measures of achievement, in which case teaching "to" them is equivalent to teaching students what they should learn anyway. But, as Ravitch explains, NCLB's top-down, high-stakes, punitive approach deters states from devising tests that come anywhere near this ideal.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Despite an abiding preference for the traditional book, I started using an e-reader about seven months ago -- and have found it insinuating itself into daily life, just as a key chain or wallet might. For there is a resemblance. A key chain or wallet (or purse) is, in a sense, simply a tool that is necessary, or at least useful, for certain purposes. But after a while, each becomes more than that to its owner. To be without them is more than an inconvenience. They are extensions of the owner's identity, or rather part of its infrastructure.Something like that has happened with the e-reader. I have adapted to it, and vice versa. Going out into the world, I bring it along, in case there are delays on the subway system (there usually are) or my medical appointment runs behind schedule (likewise). While at home, it stays within reach in case our elderly cat falls asleep in my lap. (She does so as often as possible and has grown adept at manipulating my guilt at waking her.) Right now there are about 450 items on the device. They range from articles of a few thousand words to multivolume works that, in print, run to a few hundred pages each. For a while, my acquisition of them tended to be impulsive, or at least unplanned. Whether or not the collection reflected its owner's personality, it certain documented his whims.

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas

Newsletter signup | Send us your ideas