Tap to view a larger version of these images.

Martin F. Lueken, Ph.D., Rick Esenberg & CJ Szafir, via a kind reader (PDF):

Robustness checks: Lastly, to check if the estimates from our main analysis behave differently when we modify our models, we conduct a series of robustness checks in our analysis. We estimate models with alternate specifications, disaggregate the spending variable by function, and examine an alternate data set that includes one year of school-level expenditures. Details about these approaches and their results are described and reported in Appendix B. As with our main analysis, we did not find conclusive evidence to indicate that marginal changes in spending had a significant impact on student outcomes.

Conclusion: We do not find reliable evidence in the data that a systematic relationship exists between additional spending and student outcomes. These results are similar to a larger body of research on the effectiveness of spending. Economist Eric Hanushek (2003), for example, systematically reviewed research on the effectiveness of key educational resources in U.S. schools. In examining the impact of per-pupil educational expenditures, he tallied the statistical significance and impact of 163 estimates on the impact of spending on student outcomes and found that 27% of these estimates were positive and statistically significant, while 66% were not statistically significant, meaning no impacts were detected.

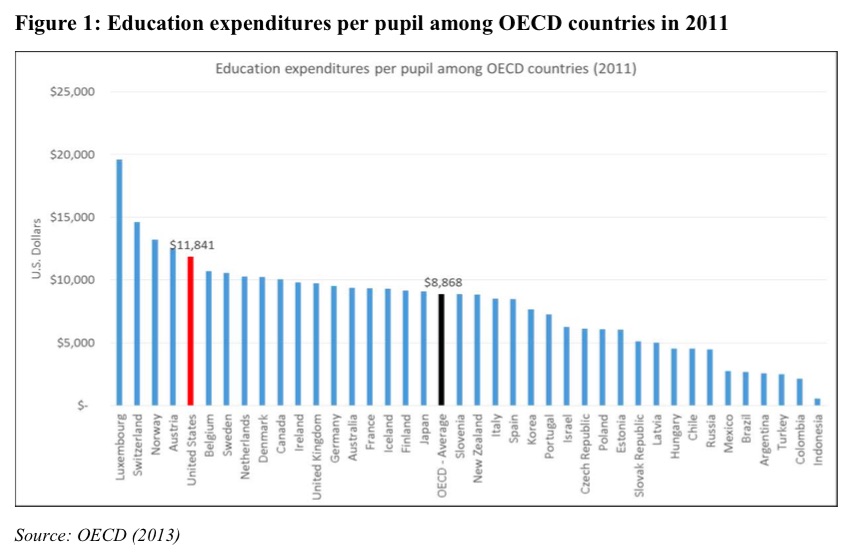

Advocates for keeping the status quo argue for increasing education spending to solve problems with our education system. But, it is not the case that resources alone will bring about improvement – even substantial infusions of resources, as was the case with Kansas City’s experience. One plausible explanation may be that districts have reached what economists call diminishing returns. This occurs when an organization reaches a point where additional dollars spent do not produce proportional benefits, holding everything else constant. For example, a dollar spent on education in developing counties, such as India, is more likely to have a greater impact than in Wisconsin – or elsewhere in the United States – which spends more than most of the developed world.

This raises a question for policymakers: Has Wisconsin hit a wall where an additional dollar in education spending will not bring improvements in student outcomes? The results of our research indicate that this may be the case.

….

Funding disparities between schools

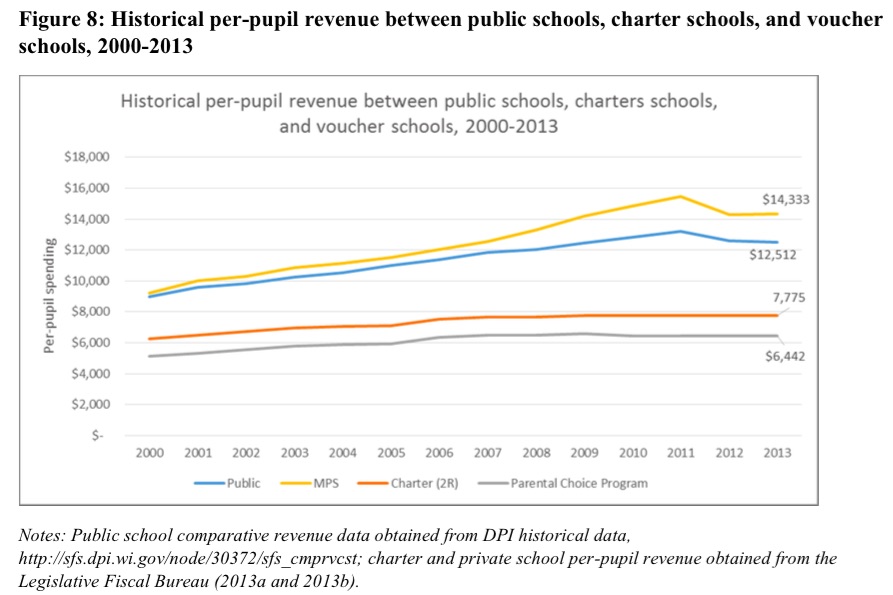

As Figure 8 shows, significant disparities in public funding exist among traditional public schools and both private schools in the choice program and independent public charter schools. The amount that independent charters and choice schools receive is set by state law. Currently, the amount of a voucher for the choice programs is $7,210 for K- 8 and $7,856 for grades 9-12.Independent charters in Milwaukee receive the same amount (state law reflects that). Public school districts, on average, receive $12,512 per pupil. Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) receives $14,333 per pupil (Figure 8).

This disparity is not new. Since 2000, expenditures increased for public schools statewide by 3% while it decreased for independent charter and private schools in the parental choice program by 7% to 8% (adjusted for inflation, i.e. “real”).43 Notably, revenues for MPS increased by 15% in real terms.

Locally, Madison spends double the national average per student, or more than $15K annually, yet has long tolerated disastrous reading results.