Search results

97 results found.

97 results found.

Value Added Resource Center @ Wisconsin Center for Education Research

Complete report 1.4MB

Summary.

Much more on value added assessment here.

Madison’s value added assessment program is based on the oft-criticized wkce.

Complete Report: 1.5MB PDF File

Value added is the use of statistical technique to identify the effects of schooling on measured student performance. The value added model uses what data are available about students–past test scores and student demographics in particular–to control for prior student knowledge, home and community environment, and other relevant factors to better measure the effects of schools on student achievement. In practice, value added focuses on student improvement on an assessment from one year to the next.

This report presents value-added results for Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) for the two-year period between November 2007 to November 2009, measuring student improvement on the November test administrations of the Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Examination (WKCE) in grades three through eight. Also presented are results for the two-year period between November 2005 to November 2007, as well as the two-year period between November 2006 to November 2008. This allows for some context from the past, presenting value added over time as a two-year moving average.

Changes to the Value Added Model

Some of the details of the value-added system have changed in 2010. The two most substantial changes are the the inclusion of differential-effects value-added results and the addition to the set of control variables of full-academic-year (FAY) attendance.

Differential Effects

In additional to overall school- and grade-level value-added measures, this year’s value-added results also include value-added measures for student subgroups within schools. The subgroups included in this year’s value-added results are students with disabilities, English language learners, black students, Hispanic students, and students who receive free or reduced-price lunches. The results measure the growth of students in these subgroups at a school. For example, if a school has a value added of +5 for students with disabilities, then students with disabilities at this school gained 5 more points on the WKCE relative to observationally similar students across MMSD.

The subgroup results are designed to measure differences across schools in the performance of students in that subgroup relative to the overall performance of students in that subgroup across MMSD. Any overall, district-wide effect of (for example) disability is controlled for in the value-added model and is not included in the subgroup results. The subgroup results reflect relative differences across schools in the growth of students in that subgroup.

Much more on “Value Added Assessment”, here.

In the two years Madison has collected and shared value-added numbers, it has seen some patterns emerging in elementary school math learning. But when compared with other districts, such as Milwaukee, Kiefer says there’s much less variation in the value- added scores of schools within the Madison district.

“You don’t see the variation because we do a fairly good job at making sure all staff has the same professional development,” he says.

Proponents of the value-added approach agree the data would be more useful if the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction were to establish a statewide value-added system. DPI is instead developing an assessment system to look at school-wide trends and improve instruction for individual students.

…..

But some question whether value-added data truly benefits all students, or is geared toward closing the gap between high- and low-performing students.

“Will the MMSD use new assessments…of students’ progress to match instruction levels with demonstrated learning levels?” asks Lorie Raihala, a Madison parent who is part of a group seeking better programming for high-achieving ninth- and 10th-graders at West High School. “So far the district has not done this.”

Others are leery of adding another measurement tool. David Wasserman, a teacher at Sennett Middle School and part of a planning group pushing to open Badger Rock Middle School, a green charter (see sidebar), made national news a few years ago when he refused to administer a mandatory statewide test. He still feels that a broad, student-centered evaluation model that takes multiple assessments into account gives the best picture.

“Assessment,” he says, “shouldn’t drive learning.”

Notes and links on “Value Added Assessment“, and the oft-criticized WKCE, on which it is based, here.

So most of you may have heard that the LA Times is doing a huge multi-part story about teacher evaluation. One of the biggest parts is a listing of every single public school teacher and their classroom test scores (and the teachers are called out by name).

From the article:Though the government spends billions of dollars every year on education, relatively little of the money has gone to figuring out which teachers are effective and why.

Seeking to shed light on the problem, The Times obtained seven years of math and English test scores from the Los Angeles Unified School District and used the information to estimate the effectiveness of L.A. teachers — something the district could do but has not.

The Times used a statistical approach known as value-added analysis, which rates teachers based on their students’ progress on standardized tests from year to year. Each student’s performance is compared with his or her own in past years, which largely controls for outside influences often blamed for academic failure: poverty, prior learning and other factors.Interestingly, the LA Times apparently had access to more than 50 elementary school classrooms. (Yes, I know it’s public school but man, you can get pushback as a parent to sit in on a class so I’m amazed they got into so many.) And guess what, these journalists, who may or may not have ever attended a public school or have kids, made these observations:

Well worth reading, particularly Maya Cole’s suggestions on Reading Recovery (60% to 42%: Madison School District’s Reading Recovery Effectiveness Lags “National Average”: Administration seeks to continue its use) spending, Administrative compensation comparison, a proposal to eliminate the District’s public information position, Ed Hughes suggestion to eliminate the District’s lobbyist (Madison is the only District in the state with a lobbyist), trade salary increases for jobs, Lucy Mathiak’s recommendations vis a vis Teaching & Learning, the elimination of the “expulsion navigator position”, reduction of Administrative travel to fund Instructional Resource Teachers, Arlene Silveira’s recommendation to reduce supply spending in an effort to fund elementary school coaches and a $200,000 reduction in consultant spending. Details via the following links:

Maya Cole: 36K PDF

Ed Hughes: 127K PDF

Lucy Mathiak: 114K PDF

Beth Moss: 10K PDF

Arlene Silveira: 114K PDF

The Madison School District Administration responded in the following pdf documents:

Much more on the proposed 2010-2011 Madison School District Budget here.

The analysis of data from 27 elementary schools and 11 middle schools is based on scores from the Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Examination (WKCE), a state test required by the federal No Child Left Behind law.

Madison is the second Wisconsin district, after Milwaukee, to make a major push toward value-added systems, which are gaining support nationally as an improved way of measuring school performance.

Advocates say it’s better to track specific students’ gains over time than the current system, which holds schools accountable for how many students at a single point in time are rated proficient on state tests.

“This is very important,” Madison schools Superintendent Daniel Nerad said. “We think it’s a particularly fair way … because it’s looking at the growth in that school and ascertaining the influence that the school is having on that outcome.”

The findings will be used to pinpoint effective teaching methods and classroom design strategies, officials said. But they won’t be used to evaluate teachers: That’s forbidden by state law.

The district paid about $60,000 for the study.

Much more on “Value Added Assessment” here.

Ironically, the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction stated the following:

“… The WKCE is a large-scale assessment designed to provide a snapshot of how well a district or school is doing at helping all students reach proficiency on state standards, with a focus on school and district-level accountability. A large-scale, summative assessment such as the WKCE is not designed to provide diagnostic information about individual students. Those assessments are best done at the local level, where immediate results can be obtained. Schools should not rely on only WKCE data to gauge progress of individual students or to determine effectiveness of programs or curriculum.”

Related:

|

Superintendent Art Rainwater gave a presentation on “Value Added Assessment” to the Madison School Board’s Performance & Achievement committee Monday evening. Art described VAA “as a method to track student growth longitudinally over time and to utilize that data to look at how successful we are at all levels of our organization”. MMSD CIO Kurt Kiefer, Ernie Morgan, Mike Christian and Rob Meyer, a senior scientist at WCER presented this information to the committee (there were two others whose names I could not decipher from the audio). |

Related Links:

“That is, there is no way of knowing whether previous WKCE tests were easier or harder than today’s, and also, DPI has changed the curve. For both reasons, we can’t use WKCE to gauge student progress (or lack of it) over time.

Pause and think about this. DPI says WKCE cannot tell us whether the academic skills of Wisconsin students are improving, staying the same, or getting worse over time.”

The fact that the School Board is actually discussing this topic is a positive change from the recent past. One paradox of this initiative is that while the MMSD is apparently collecting more student performance data, some parents (there are some teachers who provide full report cards) are actually receiving less via the report card reduction activities (more here and here). Perhaps the school district’s new parent portal will provide more up to date student data.

A few interesting quotes from the discussion:

45 minutes: Kurt has built a very rich student database over the years (goes back to 1990).

46 Superintendent Art Rainwater: We used to always have the opinion here that if we didn’t invent it, it couldn’t possibly be any good because we’re so smart that we’ve have thought of it before anybody else if it was any good. Hopefully, we’ve begun to understand that there are 15,000 school districts in America and that all of them are doing some things that we can learn from.

47 Art, continued: It’s a shame Ruth (Robarts) isn’t sitting here because a lot of things that Ruth used to ask us to do that we said we just don’t have the tools to do that with I think, over time, this will give us the tools that we need. More from Ruth here and here.

55 Arlene Silveira asked about staff reaction in Milwaukee and Chicago to this type of analysis.

69 Maya asked about how the School Board will use this to determine if this program or that program is working. Maya also asked earlier about the data source for this analysis, whether it is WKCE or NAEP. Kurt responded that they would use WKCE (which, unfortunately seems to change every few years).

71 Lawrie Kobza: This has been one of the most interesting discussions I’ve been at since I’ve been on the school board.

Lawrie, Arlene and Maya look like they will be rather active over the next 8 months.

Education News looks at the first results of N.J.’s value-added teacher evaluations, which “found that overall, 23.4% of teachers received “highly effective ratings; 73.9% of teachers were rated “effective”; 2.5% were rated “partially effective”, a rating which can affect tenure; and .02%, about 200 total teachers in the state, were rated “ineffective.” Also see NJ Spotlight, the Record, Here’s the DOE report.

American Statistical Association:

Many states and school districts have adopted Value-Added Models (VAMs) as part of educational accountability systems. The goal of these models, which are also referred to as Value-Added Assessment (VAA) Models, is to estimate effects of individual teachers or schools on student achievement while accounting for differences in student background. VAMs are increasingly promoted or mandated as a component in high-stakes decisions such as determining compensation, evaluating and ranking teachers, hiring or dismissing teachers, awarding tenure, and closing schools.

The American Statistical Association (ASA) makes the following recommendations regarding the use of VAMs:

The ASA endorses wise use of data, statistical models, and designed experiments for improving the quality of education.

VAMs are complex statistical models, and high-level statistical expertise is needed to develop the models and interpret their results.

Estimates from VAMs should always be accompanied by measures of precision and a discussion of the assumptions and possible limitations of the model. These limitations are particularly relevant if VAMs are used for high-stakes purposes.

VAMs are generally based on standardized test scores, and do not directly measure potential teacher contributions toward other student outcomes.

VAMs typically measure correlation, not causation: Effects – positive or negative – attributed to a teacher may actually be caused by other factors that are not captured in the model.

Under some conditions, VAM scores and rankings can change substantially when a different model or test is used, and a thorough analysis should be undertaken to evaluate the sensitivity of estimates to different models.

Much more on value added assessment, here.

I don’t spend much time debunking our most powerful educational fad: value-added assessments to rate teachers. My colleague Valerie Strauss eviscerates value-added several times a week on her Answer Sheet blog with the verve of a samurai, so who needs me?

Unfortunately, value-added is still growing in every corner of our nation, including D.C. schools, despite all that torn flesh and missing pieces. It’s like those monsters lumbering through this year’s action films. We’ve got to stop them! Let me fling my small, aged body in their way with the best argument against value-added I have seen in some time.

It comes from education analyst and teacher trainer Grant Wiggins and his “Granted, but . . .” blog. He starts with the reasons many people, including him and me, like the idea of value-added. Why not rate teachers by how much their students improve over time? In theory, this allows us to judge teachers in low- and high-income schools fairly, instead of declaring, as we tend to do, that the teachers in rich neighborhoods are better than those in poor neighborhoods because their students’ test scores are higher.

Much more on “value added assessment“, here.

Terry Grier, former superintendent of San Diego schools, encountered union opposition when he tried to use the novel method. His fight offers a peek at a brewing national debate.

When Terry Grier was hired to run San Diego Unified School District in January 2008, he hoped to bring with him a revolutionary tool that had never been tried in a large California school system.

Its name — “value-added” — sounded innocuous enough. But this number-crunching approach threatened to upend many traditional notions of what worked and what didn’t in the nation’s classrooms.

It was novel because rather than using tests to take a snapshot of overall student achievement, it used scores to track each pupil’s academic progress from year to year. What made it incendiary, however, was its potential to single out the best and worst teachers in a nation that currently gives virtually all teachers a passing grade.

In previous jobs in the South, Grier had used the method as a basis for removing underperforming principals, denying ineffective teachers tenure and rewarding the best educators with additional pay.

In California, where powerful teachers unions have been especially protective of tenure and resistant to merit pay, Grier had a more modest goal: to find out if students in the San Diego district’s poorest schools had equal access to effective instructors.

Eskelsen García already has fiery words for the feds, who she holds responsible for the growing use of “value-added measures,” or VAMs, an algorithm that aims to assess teacher effectiveness by student growth on standardized tests. The idea has gained traction under the Obama administration through waivers from No Child Left Behind and the administration’s signature Race to the Top program. But studies, including some funded by the Education Department, have cast doubt on the validity of the measures.

VAMs “are the mark of the devil,” Eskelsen García said.

The algorithms do aim to account for variables such as student poverty levels. But Eskelsen García said they can’t capture the complete picture.

The year she taught 22 students in one class and the year she taught 39 students in one class — “Is that factored into a value-added model? No,” she said. “Did they factor in the year that we didn’t have enough textbooks so all four fifth-grade teachers had to share them on a cart and I couldn’t send any books home to do homework with my kids?”

“It’s beyond absurd,” she added. “And anyone who thinks they can defend that is trying to sell you something.”

Locally, Madison schools have been spending money and time on value-added assessment for years.

American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten has announced that she’ll call for the end of using “value added” measures as a component in teacher-evaluation systems.

Politico first reported that the AFT is beginning a campaign to discredit the measures, beginning with the catchy (if not totally original) slogan “VAM is a sham.” We don’t yet know exactly what this campaign will encompass, but it will apparently include an appeal to the U.S. Department of Education, generally a proponent of VAM.

Value-added methods use statistical algorithms to figure out how much each teacher contributes to his or her students’ learning, holding constant factors like student demographics.

In all, though, Weingarten’s announcement is less major policy news than it is something of a retreat to a former position.

When I first interviewed Weingarten about the use of test scores in evaluation systems, in 2008, she said that educators have “a moral, statistical, and educational reason not to use these things for teacher evaluation.”

Much more on “value added assessment”, here.

One can often hear opponents of value-added referring to these methods as “junk science.” The term is meant to express the argument that value-added is unreliable and/or invalid, and that its scientific “façade” is without merit.

Now, I personally am not opposed to using these estimates in evaluations and other personnel policies, but I certainly understand opponents’ skepticism. For one thing, there are some states and districts in which design and implementation has been somewhat careless, and, in these situations, I very much share the skepticism. Moreover, the common argument that evaluations, in order to be “meaningful,” must consist of value-added measures in a heavily-weighted role (e.g., 45-50 percent) is, in my view, unsupportable.

All that said, calling value-added “junk science” completely obscures the important issues. The real questions here are less about the merits of the models per se than how they’re being used.

If value-added is “junk science” regardless of how it’s employed, then a fairly large chunk of social scientific research is “junk science.” If that’s your opinion, then okay – you’re entitled to it – but it’s not very compelling, at least in my (admittedly biased) view.

Past attempts to improve student assessment in Wisconsin provide reasons to view current efforts with caution. The promise of additional funds, the political cover of broad committees, and the satisfaction of setting less-than ambitious goals have too often led to student assessment policies that provide little meaningful information to parents, teachers, schools and taxpayers. A state assessment system should provide meaningful information to all of these groups.

Data on student progress can make the work of teachers, students, parents, administrators and policymakers more effective. It can ensure that during the course of the school year, students make progress toward their own growth targets and those who do not are flagged and interventions are done to get those students back on track. It should not come as a surprise that to have meaningful, timely data, one must administer meaningful, timely tests, and Wisconsin is falling short in this department in a number of ways.

School-level value-added analyses of student test scores are already being calculated for all schools with third- to eighth-graders statewide by a respected institution right here in Wisconsin. This information should be used by schools and districts to raise school and teacher productivity. We should continue to explore the use of value-added at the classroom level, a necessary step to implementing the new teacher-evaluation system proposed by the DPI that is statutorily required for implementation in 2014-’15.

Related: www.wisconsin2.org.

(When i wrote this, I had no idea just how deeply this would speak to people and how widely it would spread. So, I think a better title is I Dare You to Measure the Value WE Add, and I invite you to share below your value as you see it.)

Tell me how you determine the value I add to my class.

Tell me about the algorithms you applied when you took data from 16 students over a course of nearly five years of teaching and somehow used it to judge me as “below average” and “average”.

Tell me how you can examine my skills and talents and attribute worth to them without knowing me, my class, or my curriculum requirements.

Tell me how and I will tell you:

Much more on “value added assessment“, here.

Los Angeles Unified School District is embroiled in negotiations over teacher evaluations, and will now face pressure from outside the district intended to force counter-productive teacher evaluation methods into use. Yesterday, I read this Los Angeles Times article about a lawsuit to be filed by an unnamed “group of parents and education advocates.” The article notes that, “The lawsuit was drafted in consultation with EdVoice, a Sacramento-based group. Its board includes arts and education philanthropist Eli Broad, former ambassador Frank Baxter and healthcare company executive Richard Merkin.” While the defendant in the suit is technically LAUSD, the real reason a lawsuit is necessary according to the article is that “United Teachers Los Angeles leaders say tests scores are too unreliable and narrowly focused to use for high-stakes personnel decisions.” Note that, once again, we see a journalist telling us what the unions say and think, without ever, ever bothering to mention why, offering no acknowledgment that the bulk of the research and the three leading organizations for education research and measurement (AERA, NCME, and APA) say the same thing as the union (or rather, the union is saying the same thing as the testing expert). Upon what research does the other side base arguments in favor of using test scores and “value-added” measurement (VAM) as a legitimate measurement of teacher effectiveness? They never answer, but the debate somehow continues ad nauseum.

It’s not that the plaintiffs in this case are wrong about the need to improve teacher evaluations. Accomplished California Teachers has published a teacher evaluation report that has concrete suggestions for improving evaluations as well, and we are similarly disappointed in the implementation of the Stull Act, which has been allowed to become an empty exercise in too many schools and districts.

Much more on “value added assessment”, here.

Madison School Board Member Ed Hughes

Value added” or “VA” refers to the use of statistical techniques to measure teachers’ impacts on their students’ standardized test scores, controlling for such student characteristics as prior years’ scores, gender, ethnicity, disability, and low-income status.

Reports on a massive new study that seem to affirm the use of the technique have recently been splashed across the media and chewed over in the blogosphere. Further from the limelight, developments in Wisconsin seem to ensure that in the coming years value-added analyses will play an increasingly important role in teacher evaluations across the state. Assuming the analyses are performed and applied sensibly, this is a positive development for student learning.

The Chetty Study

Since the first article touting its findings was published on the front page of the January 6 New York Times, a new research study by three economists assessing the value-added contributions of elementary school teachers and their long-term impact on their students’ lives – referred to as the Chetty article after the lead author – has created as much of a stir as could ever be expected for a dense academic study.

Much more on value added assessment, here.

It is important to note that the Madison School District’s value added assessment initiative is based on the oft-criticized WKCE.

Since we’re so deep into the subject of value-added testing and the political pressures surrounding it, I thought I’d point out this recently published study tracking two and a half million students from a major urban district all the way to adulthood. (HT Whitney Tilson)

They compare teacher-specific value added on math and English scores with eventual life outcomes, and apply tests to determine whether the results are biased either by student sorting on observable variables (the life outcomes of their parents, obtained from the same life-outcome data) or unobserved variables (they use teacher switches to create a quasi-experimental approach).

Much more on value added assessment, here.

Value-added and other types of growth models are probably the most controversial issue in education today. These methods, which use sophisticated statistical techniques to attempt to isolate a teacher’s effect on student test score growth, are rapidly assuming a central role in policy, particularly in the new teacher evaluation systems currently being designed and implemented. Proponents view them as a primary tool for differentiating teachers based on performance/effectiveness.

Opponents, on the other hand, including a great many teachers, argue that the models’ estimates are unstable over time, subject to bias and imprecision, and that they rely entirely on standardized test scores, which are, at best, an extremely partial measure of student performance. Many have come to view growth models as exemplifying all that’s wrong with the market-based approach to education policy.

It’s very easy to understand this frustration. But it’s also important to separate the research on value-added from the manner in which the estimates are being used. Virtually all of the contention pertains to the latter, not the former. Actually, you would be hard-pressed to find many solid findings in the value-added literature that wouldn’t ring true to most educators.

Much more on value added assessment, here.

The Los Angeles Unified School District has declined to release to The Times the names of teachers and their scores indicating their effectiveness in raising student performance.

The nation’s second-largest school district calculated confidential “academic growth over time” ratings for about 12,000 math and English teachers last year. This fall, the district issued new ones to about 14,000 instructors that can also be viewed by their principals. The scores are based on an analysis of a student’s performance on several years of standardized tests and estimate a teacher’s role in raising or lowering student achievement.

Much more on value-added assessment, which, in Madison is based on the oft-criticized WKCE.

Value added is the use of statistical technique to isolate the contributions of schools to measured student knowledge from other influences such as prior student knowledge and demographics. In practice, value added focuses on the improvement of students from one year to the next on an annual state examination or other periodic assessment. The Value-Added Research Center (VARC) of the Wisconsin Center for Education Research produces value-added measures for schools in Madison using the Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Examination (WKCE) as an outcome. The model controls for prior-year WKCE scores, gender, ethnicity, disability, English language learner, low-income status, parent education, and full academic year enrollment to capture the effects of schools on student performance on the WKCE. This model yields measures of student growth in schools in Madison relative to each other. VARC also produces value-added measures using the entire state of Wisconsin as a data set, which yields measures of student growth in Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) relative to the rest of the state.

Some of the most notable results are:

1. Value added for the entire district of Madison relative to the rest of the state is generally positive, but it differs by subject and grade. In both 2008-09 and 2009-10, and in both math and reading, the value added of Madison Metropolitan School District was positive in more grades than it was negative, and the average value added across grades was positive in both subjects in both years. There are variations across grades and subjects, however. In grade 4, value-added is significantly positive in both years in reading and significantly negative in both years in math. In contrast, value-added in math is significantly positive–to a very substantial extent–in grade 7. Some of these variations may be the result of the extent to which instruction in those grades facilitate student learning on tested material relative to non-tested material. Overall, between November 2009 and November 2010, value-added for MMSD as a whole relative to the state was very slightly above average in math and substantially above average in reading. The section “Results from the Wisconsin Value-Added Model” present these results in detail.

2. The variance of value added across schools is generally smaller in Madison than in the state of Wisconsin as a whole, specifically in math. In other words, at least in terms of what is measured by value added, the extent to which schools differ from each other in Madison is smaller than the extent to which schools differ from each other elsewhere in Wisconsin. This appears to be more strongly the case in the middle school grades than in the elementary grades. Some of this result may be an artifact of schools in Madison being relatively large; when schools are large, they encompass more classrooms per grade, leading to more across-classroom variance being within-school rather than across-school. More of this result may be that while the variance across schools in Madison is entirely within one district, the variance across schools for the rest of the state is across many districts, and so differences in district policies will likely generate more variance across the entire state. The section “Results from the Wisconsin Value-Added Model” present results on the variance of value added from the statewide value-added model. This result is also evident in the charts in the “School Value-Added Charts from the MMSD Value-Added Model” section: one can see that the majority of schools’ confidence intervals cross (1) the district average, which means that we cannot reject the hypothesis that these schools’ values added are not different from the district average.

Even with a relatively small variance across schools in the district in general, several individual schools have values added that are statistically significantly greater or less than the district average. At the elementary level, both Lake View and Randall have values added in both reading and math that are significantly greater than the district average. In math, Marquette, Nuestro Mundo, Shorewood Hills, and Van Hise also have values added that are significantly greater than the district average. Values added are lower than the district average in math at Crestwood, Hawthorne, Kennedy, and Stephens, and in reading at Allis. At the middle school level, value added in reading is greater than the district average at Toki and lower than the district average at Black Hawk and Sennett. Value added in math is lower than the district average at Toki and Whitehorse.

3. Gaps in student improvement persist across subgroups of students. The value-added model measures gaps in student growth over time by race, gender, English language learner, and several other subgroups. The gaps are overall gaps, not gaps relative to the rest of the state. These gaps are especially informative because they are partial coefficients. These measure the black/white, ELL/non-ELL, or high-school/college-graduate-parent gaps, controlling for all variables available, including both demographic variables and schools attended. If one wanted to measure the combined effect of being both ELL and Hispanic relative to non-ELL and white, one would add the ELL/non-ELL gap to the Hispanic/white gap to find the combined effect. The gaps are within-school gaps, based on comparison of students in different subgroups who are in the same schools; consequently, these gaps do not include any effects of students of different subgroups sorting into different schools, and reflect within-school differences only. There does not appear to be an evident trend over time in gaps by race, low-income status, and parent education measured by the value-added model. The section “Coefficients from the MMSD Value-Added Model” present these results.

4. The gap in student improvement by English language learner, race, or low-income status usually does not differ substantively across schools; that between students with disabilities and students without disabilities sometimes does differ across schools. This can be seen in the subgroup value-added results across schools, which appear in the Appendix. There are some schools where value-added for students with disabilities differs substantively from overall value- added. Some of these differences may be due to differences in the composition of students with disabilities across schools, although the model already controls for overall differences between students with learning disabilities, students with speech disabilities, and students with all other disabilities. In contrast, value-added for black, Hispanic, ELL, or economically disadvantaged students is usually very close to overall value added.

Value added for students with disabilities is greater than the school’s overall value added in math at Falk and Whitehorse and in reading at Marquette; it is lower than the school’s overall value added in math at O’Keefe and Sennett and in reading at Allis, Schenk, and Thoreau. Value added in math for Hispanic students is lower than the school’s overall value added at Lincoln, and greater than the school’s overall value added at Nuestro Mundo. Value added in math is also higher for ELL and low-income students than it is for the school overall at Nuestro Mundo.

Much more on “value added assessment”, here.

In Houston, school district officials introduced a test score-based evaluation system to determine teacher bonuses, then — in the face of massive protests — jettisoned the formula after one year to devise a better one.

In New York, teachers union officials are fighting the public release of ratings for more than 12,000 teachers, arguing that the estimates can be drastically wrong.

Despite such controversies, Los Angeles school district leaders are poised to plunge ahead with their own confidential “value-added” ratings this spring, saying the approach is far more objective and accurate than any other evaluation tool available.

“We are not questing for perfect,” said L.A. Unified’s incoming Supt. John Deasy. “We are questing for much better.”

Much more on “Value Added Assessment“, here.

Classroom effectiveness can be reliably estimated by gauging students’ progress on standardized tests, Gates foundation study shows. Results come amid a national effort to reform teacher evaluations.

Teachers’ effectiveness can be reliably estimated by gauging their students’ progress on standardized tests, according to the preliminary findings of a large-scale study released Friday by leading education researchers.

The study, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, provides some of the strongest evidence to date of the validity of “value-added” analysis, whose accuracy has been hotly contested by teachers unions and some education experts who question the use of test scores to evaluate teachers.

The approach estimates a teacher’s effectiveness by comparing his or her students’ performance on standardized tests to their performance in previous years. It has been adopted around the country in cities including New York; Washington, D.C.; Houston; and soon, if local officials have their way, Los Angeles.

The $45-million Measures of Effective Teaching study is a groundbreaking effort to identify reliable gauges of teacher performance through an intensive look at 3,000 teachers in cities throughout the country. Ultimately, it will examine multiple approaches, including using sophisticated observation tools and teachers’ assessments of their own performance

Much more on value added assessment, here.

Liam Goldrick & Dr. Sara Goldrick-Rab

Seeing as I am not paid to blog as part of my daily job, it’s basically impossible for me to be even close to first out of the box on the issues of the day. Add to that being a parent of two small children (my most important job – right up there with being a husband) and that only adds to my sometimes frustration of not being able to weigh in on some of these issues quickly.

That said, here is my attempt to distill some key points and share my opinions — add value, if you will — to the debate that is raging as a result of the Los Angeles Times’s decision to publish the value-added scores of individual teachers in the L.A. Unified School District.

First of all, let me address the issue at hand. I believe that the LA Times’s decision to publish the value-added scores of individual teachers was irresponsible. Given what we know about the unreliability and variability in such scores and the likelihood that consumers of said scores will use them at face value without fully understanding all of the caveats, this was a dish that should have been sent back to the kitchen.

Although the LA Times is not a government or public entity, it does operate in the public sphere. And it has a responsibility as such an actor. Its decision to label LA teachers as ‘effective’ and ‘ineffective’ based on suspect value-added data alone is akin to an auditor secretly investigating a firm or agency without an engagement letter and publishing findings that may or may not hold water.

Frankly, I don’t care what positive benefits this decision by the LA Times might have engendered. Yes, the district and the teachers union have agreed to begin negotiations on a new evaluation system. Top district officials have said they want at least 30% of a teacher’s review to be based on value-added and have wisely said that the majority of the evaluations should depend on classroom observations. Such a development exonerates the LA Times, as some have argued. In my mind, any such benefits are purloined and come at the expense of sticking it — rightly in some cases, certainly wrongly in others — to individual teachers who mostly are trying their best.

147K PDF via a Dan Dempsey email:

The following abstract and conclusion is taken from:

Volume 4, Issue 4 – Fall 2009 – Special Issue: Key Issues in Value-Added Modeling

Would Accountability Based on Teacher Value Added Be Smart Policy? An Examination of the Statistical Properties and Policy Alternatives

Douglas N. Harris of University of Wisconsin Madison

Education Finance and Policy Fall 2009, Vol. 4, No. 4: 319-350.

Available here:

http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1162/edfp.2009.4.4.319

Abstract

Annual student testing may make it possible to measure the contributions to student achievement made by individual teachers. But would these “teacher value added” measures help to improve student achievement? I consider the statistical validity, purposes, and costs of teacher value-added policies. Many of the key assumptions of teacher value added are rejected by empirical evidence. However, the assumption violations may not be severe, and value-added measures still seem to contain useful information. I also compare teacher value-added accountability with three main policy alternatives: teacher credentials, school value-added accountability, and formative uses of test data. I argue that using teacher value-added measures is likely to increase student achievement more efficiently than a teacher credentials-only strategy but may not be the most cost-effective policy overall. Resolving this issue will require a new research and policy agenda that goes beyond analysis of assumptions and statistical properties and focuses on the effects of actual policy alternatives.

6. CONCLUSION

A great deal of attention has been paid recently to the statistical assumptions of VAMs, and many of the most important papers are contained in the present volume. The assumptions about the role of past achievement in affecting current achievement (Assumption No. 2) and the lack of variation in teacher effects across student types (Assumption No. 4) seem least problematic. However, unobserved differences are likely to be important, and it is unclear whether the student fixed effects models, or any other models, really account for them (Assumption No. 3). The test scale is also a problem and will likely remain so because the assumptions underlying the scales are untestable. There is relatively little evidence on how administration and teamwork affect teachers (Assumption No. 1).

Related: Value Added Assessment, Standards Based Report Cards and Los Angeles’s Value Added Teacher Data.

Many notes and links on the Madison School District’s student information system: Infinite Campus are here.

Jason Felch, Jason Song and Doug Smith

The fifth-graders at Broadous Elementary School come from the same world — the poorest corner of the San Fernando Valley, a Pacoima neighborhood framed by two freeways where some have lost friends to the stray bullets of rival gangs.

Many are the sons and daughters of Latino immigrants who never finished high school, hard-working parents who keep a respectful distance and trust educators to do what’s best.

The students study the same lessons. They are often on the same chapter of the same book.

Yet year after year, one fifth-grade class learns far more than the other down the hall. The difference has almost nothing to do with the size of the class, the students or their parents.

It’s their teachers.

With Miguel Aguilar, students consistently have made striking gains on state standardized tests, many of them vaulting from the bottom third of students in Los Angeles schools to well above average, according to a Times analysis. John Smith’s pupils next door have started out slightly ahead of Aguilar’s but by the end of the year have been far behind.

Much more on “Value Added Assessment” and teacher evaluations here. Locally, Madison’s Value Added Assessment evaluations are based on the oft criticized WKCE.

As a rookie mom, I used to be shocked when another parent expressed horror about a teacher I thought was a superstar. No more. The fact is that your kids’ results will vary with teachers, just as they do with pills, diets and exercise regimens.

Nonetheless, we all want our kids to have at least a few excellent teachers along the way, so it’s tempting to buy into hype about value-added measures (VAM) as a way to separate the excellent from the horrifying, or least the better from the worse.

It’s so tempting that VAM is likely to be part of a reauthorized No Child Left Behind. The problem is, researchers urge caution because of the same kinds of varied results featured in playground conversations.

Value-added measures use test scores to track the growth of individual students as they progress through the grades and see how much “value” a teacher has added.

The Madison School District has been using Value Added Assessment based on the oft – criticized WKCE.

Kurt Kiefer:

Attached are the most recent results from our MMSD value added analysis project, and effort in which we are collaborating with the Wisconsin center for Educational Research Value Added Research Center (WCERVARC). These data include the two-year models for both the 2006-2008 and 2005-2007 school year spans.

This allows us in a single report to view value added performance for consecutive intervals of time and thereby begin to identify trends. Obviously, it is a trend pattern that will provide the greatest insights into best practices in our schools.

As it relates to results, there do seem to be some patterns emerging among elementary schools especially in regard to mathematics. As for middle schools, the variation across schools is once again – as it was last year with the first set of value added results – remarkably narrow, i.e., schools perform very similar to each other, statistically speaking.

Also included in this report are attachments that show the type of information used with our school principals and staff in their professional development sessions focused on how to interpret and use the data meaningfully. The feedback from the sessions has been very positive.

Much more on the Madison School District’s Value Added Assessment program here. The “value added assessment” data is based on Wisconsin’s oft-criticized WKCE.

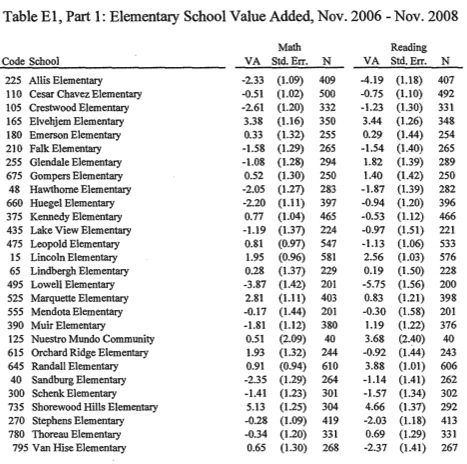

Table E1 presents value added at the school level for 28 elementary schools in Madison Metropolitan School District. Values added are presented for two overlapping time periods; the period between the November 2005 to November 2007 WKCE administrations, and the more recent period between the November 2006 and November 2008 WKCE. This presents value added as a two-year moving average to increase precision and avoid overinterpretation of trends. Value added is measured in reading and math.

VA is equal to the school’s value added. It is equal to the number ofextra points students at a school scored on the WKCE relative to observationally similar students across the district A school with a zero value added is an average school in terms of value added. Students at a school with a value added of 3 scored 3 points higher on the WKCE on average than observationally similar students at other schools.

Std. Err. is the standard error ofthe school’s value added. Because schools have only a finite number of students, value added (and any other school-level statistic) is measured with some error. Although it is impossible to ascertain the sign of measurement error, we can measure its likely magnitude by using its standard error. This makes it possible to create a plausible range for a school’s true value added. In particular, a school’s measured value added plus or minus 1.96 standard errors provides a 95 percent confidence interval for a school’s true value added.

N is the number of students used to measure value added. It covers students whose WKCE scores can be matched from one year to the next.

Wisconsin School Administrators Alliance, via a kind reader’s email [View the 146K PDF]

On August 27, 2009, State Superintendent Tony Evers stated that the State of Wisconsin would eliminate the current WKCE to move to a Balanced System of Assessment. In his statement, the State Superintendent said the following:

New assessments at the elementary and middle school level will likely be computer- based with multiple opportunities to benchmark student progress during the school year. This type of assessment tool allows for immediate and detailed information about student understanding and facilitates the teachers’ ability to re-teach or accelerate classroom instruction. At the high school level, the WKCE will be replaced by assessments that provide more information on college and workforce readiness.

By March 2010, the US Department of Education intends to announce a $350 million grant competition that would support one or more applications from a consortia of states working to develop high quality state assessments. The WI DPI is currently in conversation with other states regarding forming consortia to apply for this federal funding.

In September, 2009, the School Administrators Alliance formed a Project Team to make recommendations regarding the future of state assessment in Wisconsin. The Project Team has met and outlined recommendations what school and district administrators believe can transform Wisconsin’s state assessment system into a powerful tool to support student learning.

Criteria Underlying the Recommendations:

- Wisconsin’s new assessment system must be one that has the following characteristics:

- Benchmarked to skills and knowledge for college and career readiness • Measures student achievement and growth of all students

- Relevant to students, parents, teachers and external stakeholders

- Provides timely feedback that adds value to the learning process • Efficient to administer

- Aligned with and supportive of each school district’s teaching and learning

- Advances the State’s vision of a balanced assessment system

Wisconsin’s Assessment test: The WKCE has been oft criticized for its lack of rigor.

The WKCE serves as the foundation for the Madison School District’s “Value Added Assessment” initiative, via the UW-Madison School of Education.

Bill Clinton may have invented triangulation – the art of finding a “third way” out of a policy dilemma – but U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan is practicing it to make desperately needed improvements in K-12 education. Unfortunately, his promotion of value-added education through “Race to the Top” grants to states could be thrown under the bus by powerful teachers’ unions that view reforms more for how they affect pay and job security than whether they improve student learning.

The traditional view of education holds that it is more process than product. Educators design a process, hire teachers and administrators to run it, put students through it and consider it a success. The focus is on the inputs – how much can we spend, what curriculum shall we use, what class size is best – with very little on measuring outputs, whether students actually learn. The popular surveys of America’s best schools and colleges reinforce this, measuring resources and reputation, not results. As they say, Harvard University has good graduates because it admits strong applicants, not necessarily because of what happens in the educational process.

In the last decade, the federal No Child Left Behind program has ushered in a new era of testing and accountability, seeking to shift the focus to outcomes. But this more businesslike approach does not always fit a people-centered field such as education. Some students test well, and others do not. Some schools serve a disproportionately high number of students who are not well prepared. Even in good schools, a system driven by testing and accountability incentivizes teaching to the test, neglecting other important and interesting ways to engage and educate students. As a result, policymakers and educators have been ambivalent, at best, about the No Child Left Behind regime.

“Value Added Assessment” is underway in Madison, though the work is based in the oft-criticized state WKCE examinations.

Rob Meyer can’t help but get excited when he hears President Barack Obama talking about the need for states to start measuring whether their teachers, schools and districts are doing enough to help students succeed.

“What he’s talking about is what we are doing,” says Meyer, director of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Value-Added Research Center.

If states hope to secure a piece of Obama’s $4.35 billion “Race to the Top” stimulus money, they’ll have to commit to using research data to evaluate student progress and the effectiveness of teachers, schools and districts.

Crunching numbers and producing statistical models that measure these things is what Meyer and his staff of 50 educators, researchers and various stakeholders do at the Value-Added Research Center, which was founded in 2004. These so-called “value-added” models of evaluation are designed to measure the contributions teachers and schools make to student academic growth. This method not only looks at standardized test results, but also uses statistical models to take into account a range of factors that might affect scores – including a student’s race, English language ability, family income and parental education level.

“What the value-added model is designed to do is measure the effect and contribution of the educational unit on a student, whether it’s a classroom, a team of teachers, a school or a program,” says Meyer. Most other evaluation systems currently in use simply hold schools accountable for how many students at a single point in time are rated proficient on state tests.

Much more on “value added assessment” here, along with the oft-criticized WKCE test, the soft foundation of much of this local work.

Kurt Kiefer, Madison School District Chief Information Officer [150K PDF]:

Attached is a summary of the results form a recently completed research project conducted by The Value Added Research center (VARC) within the UW-Madison Wisconsin Center for Educational Research (WCER). Dr. Rob Meyer and Dr. Mike Christian will be on hand at the September 14 Board of Education meeting to review these findings.

The study was commissioned by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction (DPI). Both the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) and Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) were district participants. The purpose of the study was to determine the feasibility of a statewide value added statistical model and the development of state reporting and analysis prototypes. We are pleased with the results in that this creates yet one more vehicle through which we may benchmark our district and school performance.

At the September 14, 2009 Board meeting we will also share plans for continued professional development with our principals and staff around value added during the upcoming school year.

In November we plan to return to the Board with another presentation on the 2008-09 results that are to include additional methods of reporting data developed by VARC in conjunction with MPS and the DPI. We will also share progress with the professional development efforts.

Related:

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction [150K PDF], via a kind reader’s email:

Wisconsin needs a comprehensive assessment system that provides educators and parents with timely and relevant information that helps them make instructional decisions to improve student achievement,” said State Superintendent Elizabeth Burmaster in announcing members of a statewide Next Generation Assessment Task Force.

Representatives from business, commerce, and education will make recommendations to the state superintendent on the components of an assessment system that are essential to increase student achievement. Task force members will review the history of assessment in Wisconsin and learn about the value, limitations, and costs of a range of assessment approaches. They will hear presentations on a number of other states’ assessment systems. Those systems may include ACT as part of a comprehensive assessment system, diagnostic or benchmark assessments given throughout the year, or other assessment instruments and test administration methods. The group’s first meeting will be held October 8 in Madison.

A few notes:

.

Madison School Board Member Ed Hughes, writing in this week’s Isthmus:

A couple of weeks ago in these pages, Marc Eisen had some harsh words for the work of the Madison school district’s Equity Task Force (“When Policy Trumps Results,” 5/2/09). As a new school board member, I too have some doubts about the utility of the task force’s report. Perhaps it’s to be expected that while Eisen’s concerns touch on theory and rhetoric, mine are focused more on the nitty-gritty of decision making.

The smart and dedicated members of the Equity Task Force were assigned an impossible task: detailing an equity policy for me and other board members to follow. Equity is such a critical and nuanced consideration in school board decisions that, to be blunt, I’m not going to let any individual or group tell me what to do.

I am unwilling to delegate my responsibility to exercise my judgment on equity issues to a task force, no matter how impressive the group. Just as one school board cannot bind a future school board’s policymaking, I don’t think that the deliberations of a task force can restrict my exercise of independent judgment.

Admittedly, the task force faced a difficult challenge. It was obligated by the nature of its assignment to discuss equity issues in the abstract and offer up broad statements of principle.

Not surprisingly, most of the recommendations fall into the “of course” category. These include “Distribute resources based on student needs” and “Foster high academic expectations for all students.” I agree.

Related:

Wisconsin Center for Education Research: 4/22 to 4/24/2008 Madison.

Related: Value added assessment and the Madison School District.

Motoko Rich in the New York Times describes the federal lawsuit, initiated by seven Florida teachers with support from local NEA affiliates, which contends that the Florida DOE’s system of grading teachers based on student outcomes “violates teachers’ rights of due process and equal protection.”

Much more on “value added assessment, here“. Madison’s value added assessment scheme relies on the oft-criticized WKCE.

Nearly 30,000 public school teachers and support staff went on strike in Chicago this past week in a move that left some 350,000 students without classes to attend.

And while this contentious battle between Chicago Public Schools and the Chicago Teachers Union blew up due to a range of issues — including compensation, health care benefits and job security concerns — one of the key sticking points reportedly was over the implementation of a new teacher evaluation system.

That’s noteworthy locally because researchers with UW-Madison’s Value Added Research Center (VARC) have been collaborating with the Chicago Public Schools for more than five years now in an effort to develop a comprehensive program to measure and evaluate the effectiveness of schools and teachers in that district.

But Rob Meyer, the director of VARC, says his center has stayed above the fray in this showdown between the Chicago teachers and the district, which appears close to being resolved.

“The controversy isn’t really about the merits of value-added and what we do,” says Meyer. “So we’ve simply tried to provide all the stakeholders in this discussion the best scientific information we can so everybody knows what they’re talking about.”

Much more on “value added assessment”, here.

New York City on Friday released internal rankings of about 18,000 public schoolteachers who were measured over three years on their ability to affect student test scores.

The release of teacher’s job-performance data follows a yearlong legal battle with the United Federation of Teachers, which sued to block the release and protect teachers’ privacy. News organizations, including The Wall Street Journal, had requested the data in 2010 under the state Freedom of Information Law.

Friday’s release covers math and English teachers active between 2007 and 2010 in fourth- through eighth-grade classrooms. It does not include charter school teachers in those grades.

Schools Chancellor Dennis Walcott, who has pushed for accountability based on test scores, cautioned that the data were old and represented just one way to look at teacher performance.

“I don’t want our teachers disparaged in any way and I don’t want our teachers denigrated based on this information,” Mr. Walcott said Friday while briefing reporters on the Teacher Data Reports. “This is very rich data that has evolved over the years. … It’s old data and it’s just one piece of information.”

Related:

Stephanie Banchero & David Kesmodel:

Teacher evaluations for years were based on brief classroom observations by the principal. But now, prodded by President Barack Obama’s $4.35 billion Race to the Top program, at least 26 states have agreed to judge teachers based, in part, on results from their students’ performance on standardized tests.

So with millions of teachers back in the classroom, many are finding their careers increasingly hinge on obscure formulas like the one that fills a whiteboard in an economist’s office here.

The metric created by Value-Added Research Center, a nonprofit housed at the University of Wisconsin’s education department, is a new kind of report card that attempts to gauge how much of students’ growth on tests is attributable to the teacher.

For the first time this year, teachers in Rhode Island and Florida will see their evaluations linked to the complex metric. Louisiana and New Jersey will pilot the formulas this year and roll them out next school year. At least a dozen other states and school districts will spend the year finalizing their teacher-rating formulas.

“We have to deliver quality and speed, because [schools] need the data now,” said Rob Meyer, the bowtie-wearing economist who runs the Value-Added Research Center, known as VARC, and calls his statistical model a “well-crafted recipe.”

Much more on value added assessment, here.

What does just about every fifth-grader know that stumps experts?

Who the best teachers are in that kid’s school. Who’s hard, who’s easy, who makes you work, who lets you get away with stuff, who gets you interested in things, who’s not really on top of what’s going on. In other words: how good each teacher is.

A lot of the time, the fifth-grader’s opinions are on target.

But would you want to base a teacher’s pay or career on that?

Sorry, the experts are right. It’s tough to get a fair, thorough and insightful handle on how to judge a teacher.

“If there was a magic answer for this, somebody would have thought of it a long time ago,” Bradley Carl of Wisconsin Center for Education Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison: told a gathering of about 100 educators and policy-makers last week.

The Wisconsin Center for Education Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison has been working on “Value Added Assessment” using the oft-criticized WKCE.

Madison students are slated to get a double dose of standardized tests in the coming years as the state redesigns its annual series of exams while school districts seek better ways to measure learning.

For years, district students in grades three through eight and grade 10 have taken the Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Examination (WKCE), a series of state-mandated tests that measure school accountability.

Last month, in addition to the state tests, eighth- and ninth-graders took one of three different tests the district plans to introduce in grades three through 10. Compared with the WKCE, the tests are supposed to more accurately assess whether students are learning at, above or below grade level. Teachers also will get the results more quickly.

“Right now we have a vacuum of appropriate assessment tools,” said Tim Peterson, Madison’s assistant director of curriculum and assessment. “The standards have changed, but the measurement tool that we’re required by law to use — the WKCE — is not connected.”

Related Links:

I’m glad that the District is planning alternatives to the WKCE.

When it comes to the quality of Madison’s public schools, the issue is pretty much black and white.

The Madison Metropolitan School District’s reputation for providing stellar public education is as strong as it ever was for white, middle-class students. Especially for these students, the district continues to post high test scores and turn out a long list of National Merit Scholars — usually at a rate of at least six times the average for a district this size.

But the story is often different for Hispanic and black kids, and students who come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.

Madison is far from alone in having a significant performance gap. In fact, the well-documented achievement gap is in large measure responsible for the ferocious national outcry for more effective teachers and an overhaul of the public school system. Locally, frustration over the achievement gap has helped fuel a proposal from the Urban League of Greater Madison and its president and CEO, Kaleem Caire, to create a non-union public charter school targeted at minority boys in grades six through 12.

“In Madison, I can point to a long history of failure when it comes to educating African-American boys,” says Caire, who is black, a Madison native and a graduate of West High School. “We have one of the worst achievement gaps in the entire country. I’m not seeing a concrete plan to address that fact, even in a district that prides itself on innovative education.”

What often gets lost in the discussion over the failures of public education, however, is that there are some high-poverty, highly diverse schools that are beating the odds by employing innovative ways to reach students who have fallen through the cracks elsewhere.

Related: A Deeper Look at Madison’s National Merit Scholar Results.

Troller’s article referenced use of the oft criticized WKCE (Wisconsin Knowledge & Concepts Examination) (WKCE Clusty search) state examinations.

Related: value added assessment (based on the WKCE).

Dave Baskerville has argued that Wisconsin needs two big goals, one of which is to “Lift the math, science and reading scores of all K-12, non-special education students in Wisconsin above world-class standards by 2030”. Ongoing use of and progress measurement via the WKCE would seem to be insufficient in our global economy.

Steve Chapman on “curbing excellence”.

Wisconsin Education Association Council:

State officers of the Wisconsin Education Association Council (WEAC) today unveiled three dramatic proposals as part of their quality-improvement platform called “Moving Education Forward: Bold Reforms.” The proposals include the creation of a statewide system to evaluate educators; instituting performance pay to recognize teaching excellence; and breaking up the Milwaukee Public School District into a series of manageable-sized districts within the city.

“In our work with WEAC leaders and members we have debated and discussed many ideas related to modernizing pay systems, better evaluation models, and ways to help turn around struggling schools in Milwaukee,” said WEAC President Mary Bell. “We believe bold actions are needed in these three areas to move education forward. The time for change is now. This is a pivotal time in public education and we’re in an era of tight resources. We must have systems in place to ensure high standards for accountability – that means those working in the system must be held accountable to high standards of excellence.”

TEACHER EVALUATION: In WEAC’s proposed teacher evaluation system, new teachers would be reviewed annually for their first three years by a Peer Assistance and Review (PAR) panel made up of both teachers and administrators. The PAR panels judge performance in four areas:

- Planning and preparing for student learning

- Creating a quality learning environment

- Effective teaching

- Professional responsibility

The proposed system would utilize the expertise of the UW Value-Added Research Center (Value Added Assessment) and would include the review of various student data to inform evaluation decisions and to develop corrective strategies for struggling teachers. Teachers who do not demonstrate effectiveness to the PAR panels are exited out of the profession and offered career transition programs and services through locally negotiated agreements.

Veteran teachers would be evaluated every three years, using a combination of video and written analysis and administrator observation. Underperforming veteran teachers would be required to go through this process a second year. If they were still deemed unsatisfactory, they would be re-entered into the PAR program and could ultimately face removal.

“The union is accepting our responsibility for improving the quality of the profession, not just for protecting the due process rights of our members,” said Bell. “Our goal is to have the highest-quality teachers at the front of every classroom across the state. And we see a role for classroom teachers to contribute as peer reviewers, much like a process often used in many private sector performance evaluation models.”

“If you want to drive change in Milwaukee’s public schools, connect the educators and the community together into smaller districts within the city, and without a doubt it can happen,” said Bell. “We must put the needs of Milwaukee’s students and families ahead of what’s best for the adults in the system,” said Bell. “That includes our union – we must act differently – we must lead.”

Madison’s “value added assessment” program is based on the oft-criticized WKCE examinations.

Related: student learning has become focused instead on adult employment – Ripon Superintendent Richard Zimman.

SEATTLE Public Schools is right to push for a better, more honest way of evaluating teachers, even at the risk of a strike.

Tense contract negotiations between the district and the Seattle Education Association underscore the enormous opportunity at stake. Both sides agree the current system used to judge teachers is weak and unreliable. Ineffective teachers are ignored or shuffled to other schools to become other parents’ nightmare. Excellent teachers languish in a system that has no means to recognize or reward them.

The union leadership called for a few tweaks. But the district proposed a revamped system using student growth, as measured by test scores. Supporters of the status quo have tried to downplay the other forms of appraisal that would be used. They include student growth measurements selected by the teacher, principal observations of instruction and peer reviews. Also, student input at the high-school level.

Much more an value added assessment, here.

For instance, he’s the only state elected official to actually and seriously float a proposal to repair the broken state funding system for schools. He promises the proposal for his “Funding for Our Future” will be ready to introduce to lawmakers this fall and will include details on its impact on the state’s 424 school districts.

Evers also is interested in the potential of charter schools. Let’s be open and supportive about education alternatives, he says, but mindful of what’s already working well in public schools.

And he says qualified 11th and 12th graders should be allowed to move directly on to post-secondary education or training if they wish. Dual enrollment opportunites for high school age students attending college and technical schools will require a shift in thinking that shares turf and breaks down barriers, making seamless education — pre-K through post-secondary — a reality instead of some distant dream, according to Evers.

As to Evers’ comments on teacher testing, he joins a national conversation that has been sparked, in part, by the Obama administration as well as research that shows the single universal element in improved student performance is teacher quality. We recently featured a story about concerns over teacher evaluation based on student performance and test scores, and the issue has been a potent topic elsewhere, as well.

The proof, as always, is in the pudding, or substance.

Melissa Westbrook wrote a very useful and timely article on education reform:

I think many ed reformers rightly say, “Kids can’t wait.” I agree.

There is nothing more depressing than realizing that any change that might be good will likely come AFTER your child ages out of elementary, middle or high school. Not to say that we don’t do things for the greater good or the future greater good but as a parent, you want for your child now. Of course, we are told that change needs to happen now but the reality is what it might or might not produce in results is years off. (Which matters not to Bill Gates or President Obama because their children are in private schools.)

All this leads to wonder about our teachers and what this change will mean. A reader, Lendlees, passed on a link to a story that appeared in the LA Times about their teacher ratings. (You may recall that the LA Times got the classroom test scores for every single teacher in Los Angeles and published them in ranked order.)

Susan Troller notes that Wisconsin’s oft criticized WKCE (on which Madison’s value added assessment program is based) will be replaced – by 2014:

Evers also promised that the much maligned Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Exam, used to test student proficiency in 3rd through 6th, 8th and 10th grades, is on its way out. By 2014, there will be a much better assessment of student proficiency to take its place, Evers says, and he should know. He’s become a leading figure in the push for national core education standards, and for effective means for measuring student progress.

So you want to know if the teacher your child has for the new school year is the star you’re hoping for. How do you find out?

Well, you can ask around. Often even grade school kids will give you the word. But what you hear informally might be on the mark and might be baloney. Isn’t there some way to get a good answer?

Um, not really. You want a handle on how your kid is doing, there’s plenty of data. You want information on students in the school or the school district, no problem.

But teachers? If they had meaningful evaluation reports, the reports would be confidential. And you can be quite confident they don’t have evaluations like that – across the U.S., and certainly in Wisconsin, the large majority of teachers get superficial and almost always favorable evaluations based on brief visits by an administrator to their classrooms, research shows. The evaluations are of almost no use in actually guiding teachers to improve.

Perhaps you could move to Los Angeles. The Los Angeles Times began running a project last Sunday on teachers and the progress students made while in their classes. It named a few names and said it will unveil in coming weeks specific data on thousands of teachers.

Related: Value added assessment.

Local school districts have started to grade teachers based on student test scores, but the early results suggest the effort deserves an incomplete.

The new type of teacher evaluations make use of the standardized tests that have become an annual rite for American public-school students. The tests mainly have been used to measure the progress of students and schools, but with some statistical finesse they can be transformed into a lens for identifying which teachers are producing the best test results.

At least, that’s the hope among some education experts. But the performance numbers that have emerged from these studies rely on a flawed statistical approach.

One perplexing finding: A large proportion of teachers who rate highly one year fall to the bottom of the charts the next year. For example, in a group of elementary-school math teachers who ranked in the top 20% in five Florida counties early last decade, more than three in five didn’t stay in the top quintile the following year, according to a study published last year in the journal Education Finance and Policy.

Related: Standards Based Report Cards and Value Added Assessment.

Test early, test often, and make sure the results you get are meaningful to students, teachers and parents.

Although that may sound simple, in the last three years it’s become a mantra in the Monona Grove School District that’s helping all middle and high school students increase their skills, whether they’re heading to college or a career. The program, based on using ACT-related tests, is helping to establish the suburban Dane County district as a leader in educational innovation in Wisconsin.

In fact, Monona Grove recently hosted a half-day session for administrators and board members from Milwaukee and Madison who were interested in learning more about Monona Grove’s experiences and how the school community is responding to the program. In a pilot program this spring in Madison, students in eighth grade at Sherman Middle School will take ACT’s Explore test for younger students. At Memorial, freshmen will take the Explore test.

Known primarily as a college entrance examination, ACT Inc. also provides a battery of other tests for younger students. Monona Grove is using these tests — the Explore tests for grades 8 and 9, and the Plan tests for grades 10 and 11 — to paint an annual picture of each student’s academic skills and what he or she needs to focus on to be ready to take on the challenges of post-secondary education or the work force. The tests are given midway through the first semester, and results are ready a month later.