Dave Cieslewicz:

Maia Pearson, the chair of Madison’s police oversight board and a Madison school board member, has been charged with criminal misdemeanors related to her resisting arrest in an incident in downtown Madison in December.

In a criminal complaint, it is alleged that she and her friend, Urban Triage executive director Brandi Grayson, verbally abused staff at a theatre and then physically resisted arrest and failed to comply with the orders of police at the scene. At one point the official complaint states that three or four cops had to remove her from her vehicle and then she extended her legs in the police vehicle so that the door could not be closed.

You might think that Pearson would be under investigation or some sort of official inquiry by both the school district and the city to see if she should be allowed to continue in her roles.

Instead, apparently, it’s not Pearson who’s the subject of deeper inquires, but the cops who arrested her.

If you find that incredible, join the club. But immediately following Pearson’s arrest on December 19th, the interim Police Monitor, Aeiramique Glass, who answers to Pearson’s board, announced that she was investigating the incident. Of course, the first question the public might be asking is, ‘investigating who for what?’

The Police Monitor is supposed to be a complaint driven process. In fact, the complaint process is so central that it took the previous Monitor two years to so much as come up with a complaint form. So, who filed a complaint here? Did Pearson complain about her arrest? We have no information, but right now we’d have to assume that Glass initiated the process on her own.

That conclusion was backed up today when it was reported that City Attorney Mike Haas ruled on a question of conflict of interest. In his informal ruling, he wrote: “It seems to me that if the focus of any such investigation is the actions of police officers and not the Board Chair, the Independent Monitor has the authority to investigate activities of the Police Department.”

——-

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

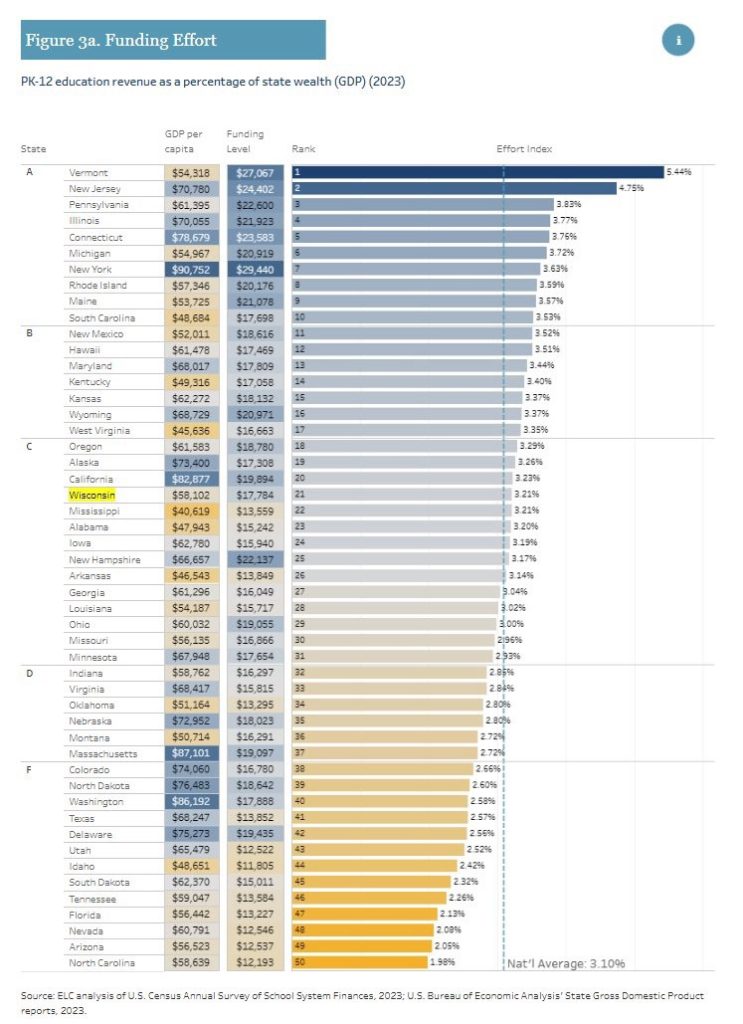

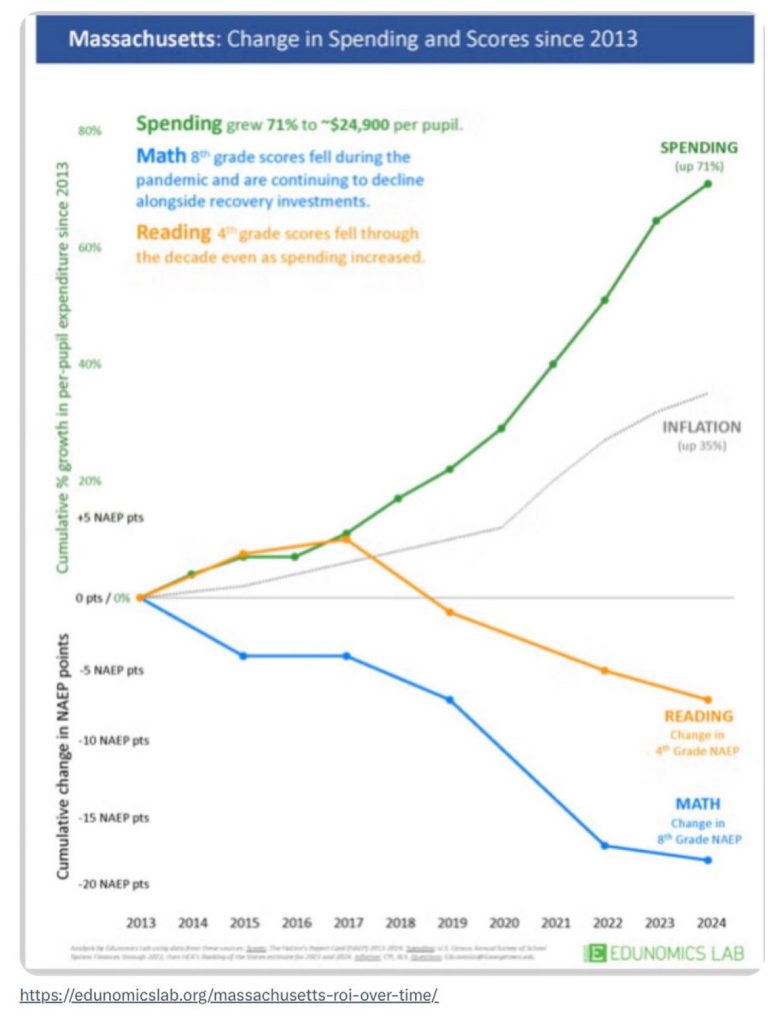

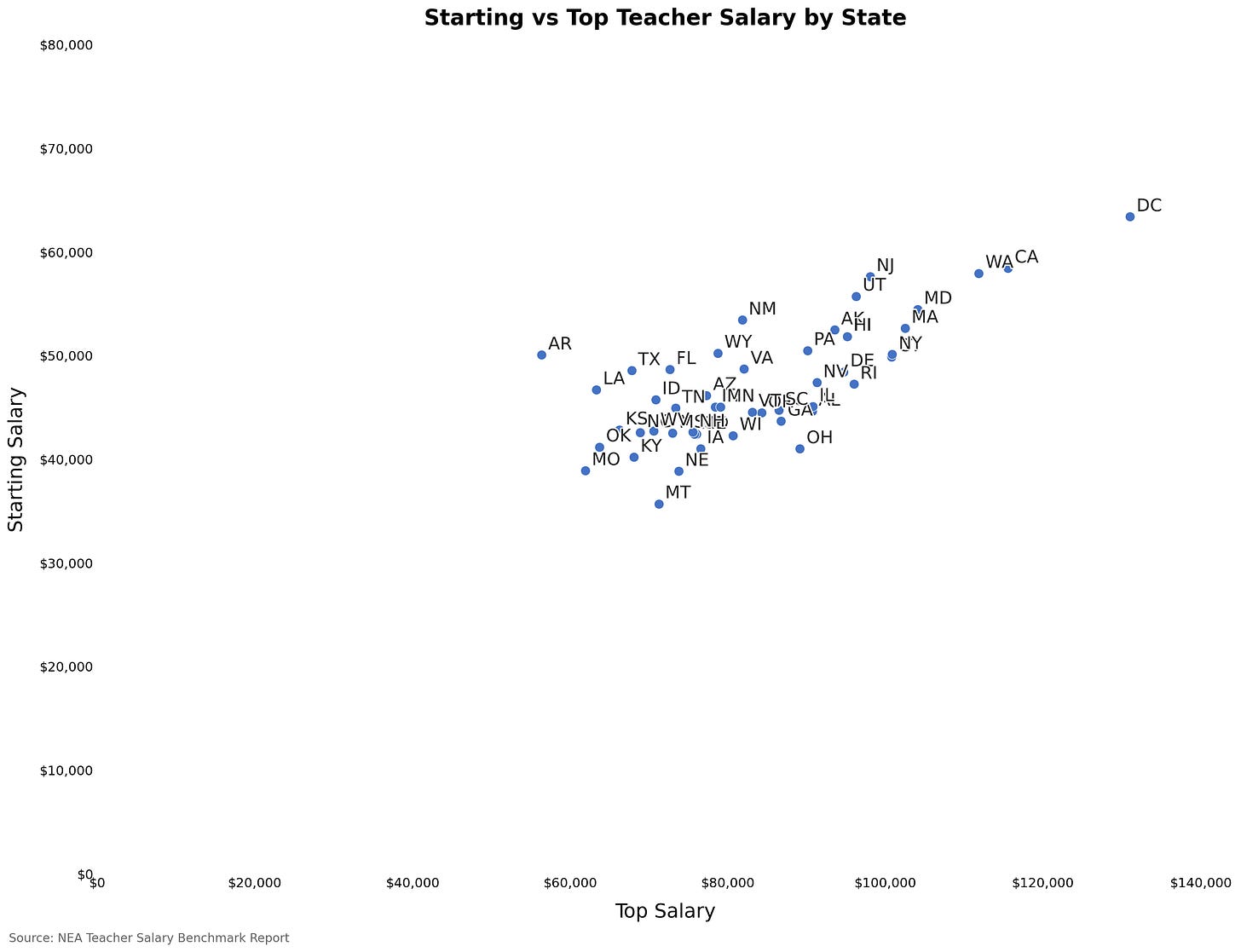

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

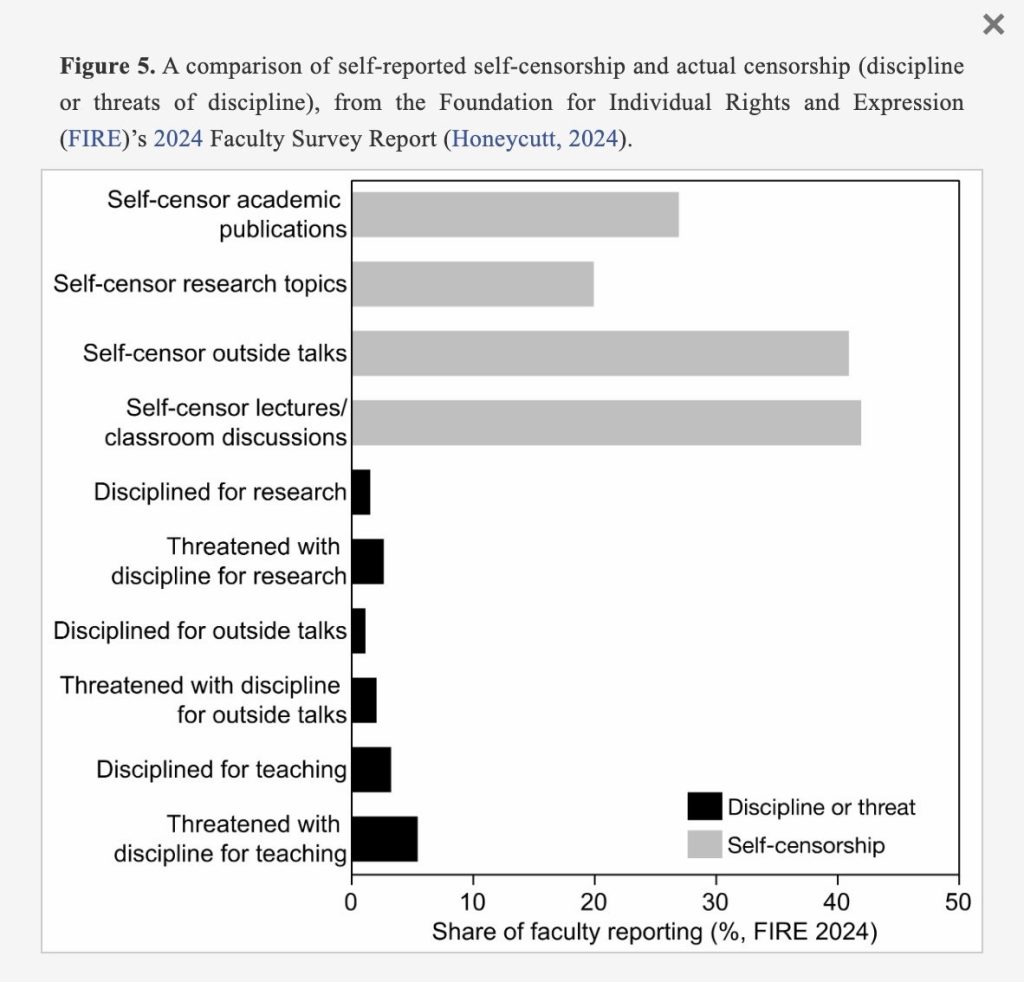

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy