David J. Farber, a gregarious professor of computer networks who was sometimes called the “grandfather of the internet” because of the ultimately groundbreaking students he trained, died on Feb. 7 in Tokyo. He was 91.

His son Emanuel said the apparent cause was heart failure. Professor Farber had been teaching at Keio University in Tokyo since 2018.

When Professor Farber started his career in the mid-1950s, at Bell Laboratories, computers were practically islands unto themselves. If they communicated at all, they talked by means of a Teletype or punch card reader down the hall.

Since then, thanks in part to his work, the realms of communication and computation merged into that one powerful glue for society that is the internet; The New York Times once described him as “an early architect” of it.

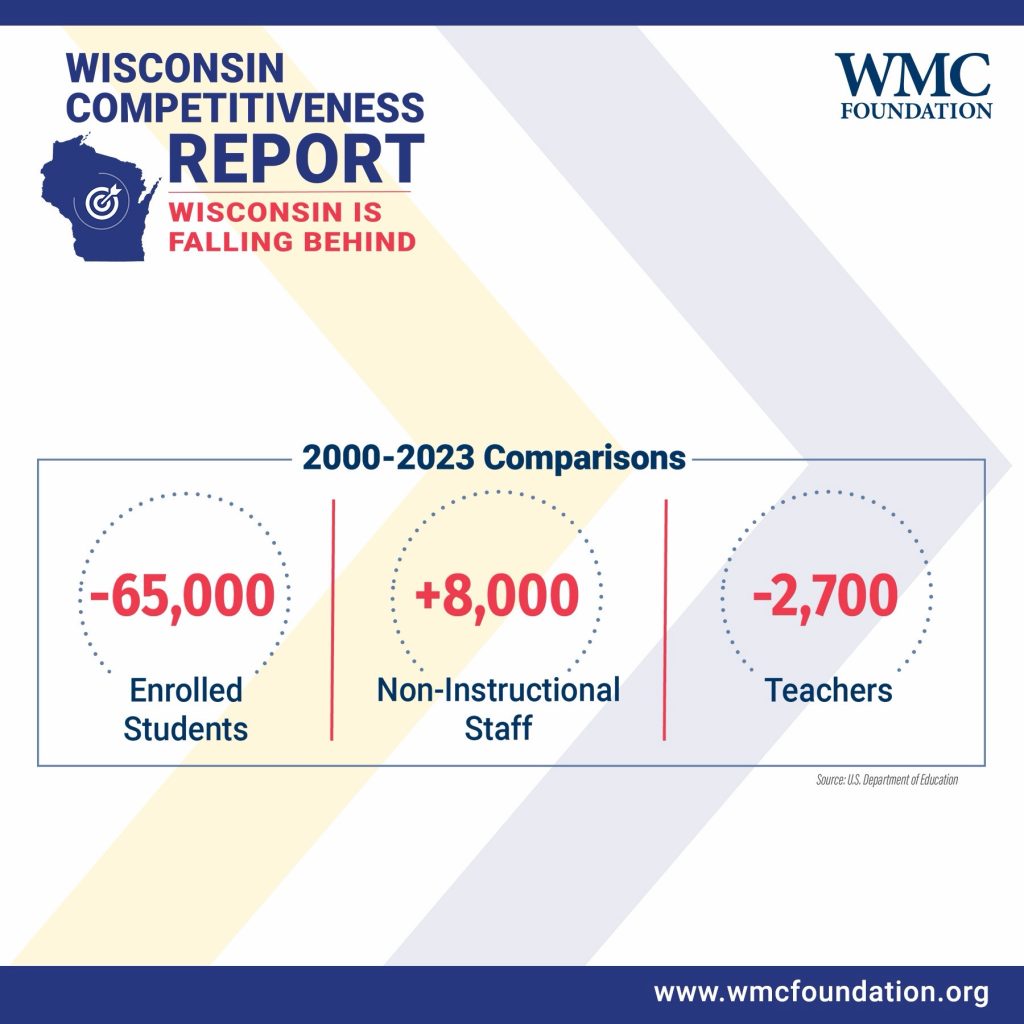

K-12 Tax, $pending & Governance Climate: The inefficiencies of Public Sector Unions

Nicholas Bagley and Robert Gordon:

They will have to push back against a core constituency within the Democratic Party that often makes government deliver less and cost more: unions representing teachers, police officers and transit workers.

Democrats have long accepted inefficiencies as the price of support from public sector unions, and this may seem the worst time to demand better. Confronted with the president’s cruelty and lawlessness, the unions have been inspiring: defending wrongly fired workers, fighting federal overreach and organizing against ICE brutality.

But it’s precisely because of increasing authoritarianism that Democratic governors and mayors need to show the public that they can deliver. With the president weaponizing budget cuts against blue states, there is little room for error. Democrats need a new bargain with public sector unions — one that respects their voices and livelihoods but puts public services first.

Begin with the cost of government. Blue-state and blue-city voters pay higher taxes. More than half of city and local government expenditures (and 20 percent of state expenditures) are paid out to employees. These blue states and cities often also pay state and local government workers more than similar jobs pay in red jurisdictions, even after adjusting for the cost of living.

Much of this gap is tied up in pension benefits. Workers generally valuehigherwages today more than retirement guarantees in the future. But pensions are attractive to politicians who pass future costs to future taxpayers. And it is the job of unions to fight for the largest benefits they can.

———

“The new [Chicago pension] law will cost the city $60 million next year — more than enough money to cover the city’s summer job program — before ballooning to $11 billion over three decades. Because of Illinois’s Constitution, the commitments cannot be reversed.”

———

more.

———

Related: Act 10

k-12 Tax & $pending climate: School levy tax credits reward big spenders at the expense of frugal districts

Complex system insulates districts that agree to raise taxes the fastest

You might be paying higher school property taxes this year because of a referendum to exceed a school district’s revenue cap — one that you did not get a vote on in a district your kids do not attend.

That’s because of the structure of Wisconsin’s school levy tax credit, under which property owners in some school districts have seen their school levy tax credits shrink to subsidize additional spending in other districts where they have no vote and no representation.

Donald Knuth on the History of Science

Knuth then enumerated his motivations, as a computer scientist, to read the history of science. First, reading history helped him to understand the process of discovery. Second, understanding the difficulty and false starts experienced by brilliant historical scientists in making discoveries that specialists now find obvious helped him to see what made concepts challenging to students and thus to become a “much better writer and teacher.” Third, appreciating the historical contribution of non-Western scientists helped in “celebrating the contributions of many cultures.” Fourth, history is the craft of telling stories, which is “the best way to teach, to explain something.” Fifth, the biographies of scientists teach tactics for a successful and rewarding career. Sixth, history teaches how human experience has changed over time. As humans we should care about that.

Knuth also identified some special contributions to the history of science that professionally trained historians are uniquely well placed to make. We are good at “smoking out” primary sources and putting historical activities in the context of broader timelines. He also appreciates our ability to translate papers written in languages that he cannot himself read. He finds attempts at historical analysis “probably the least interesting” aspects of our papers but appreciates lengthy quotations from primary sources.

k-12 Tax & $pending Climate: Bernie Sanders Can’t Explain American Innovation

Asked point-blank why the US dominates tech while Europe stagnates, the Senator pivoted to healthcare and homelessness. The honest answer would destroy his worldview.

Stanford Economics researcher Sid Gundapaneni (@MacroscopeEcon on X) asked Bernie Sanders a simple question: “What institutional or economic features explain this difference?” between US and European tech innovation. Europe has produced zero of the world’s ten largest frontier tech firms. America dominates.

Bernie’s response was textbook evasion.

He never answered the question. He couldn’t. Because the honest answer would require admitting that European-style redistribution correlates with zero frontier tech companies.

Why Hold Your Straight-A Student Back a Year? To Get a Better Endorsement Deal

As high school approached, Cancelleri decided that wasn’t enough. He paid about $20,000 for his son, a straight-A student, to repeat a grade at a private middle school sports academy.

“The draw to it [was] just giving him a little bit of extra time to develop and mature,” said Cancelleri, whose 15-year-old son, Carter, has grown about 3 inches since August and hopes to be a strong competitor next year as a high school freshman.

Sixty other boys are repeating a grade at the same academy, The Togethership, where coursework includes throwing mechanics, game film review and nutrition along with traditional subjects such as Algebra and English.

The U.S. spent $30 billion to ditch textbooks for laptops and tablets: The result is the first generation less cognitively capable than their parents

He said Gen Z is the first generation in modern history to score lower on standardized tests than the previous one.

While skills measured by these tests, like literacy and numeracy, aren’t always indicative of intelligence, they are a reflection of cognitive capability, which Horvath said has been on the decline over the last decade or so.

Citing Program for International Student Assessmentdata taken from 15-year-olds across the world and other standardized tests, Horvath noted not only dipping test scores, but also a stark correlation in scores and time spent on computers in school, such that more screen time was related to worse scores. He blamed students having unfettered access to technology that atrophied rather than bolstered learning capabilities. The introduction of the iPhone in 2007 also didn’t help.

“This is not a debate about rejecting technology,” Horvath wrote. “It is a question of aligning educational tools with how human learning actually works. Evidence indicates that indiscriminate digital expansion has weakened learning environments rather than strengthened them.”

———

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

Outrage as NY teacher ousted after helping kids start a Turning Point USA club at high school

An upstate New York high school teacher was allegedly sidelined after she agreed to advise a Turning Point USA chapter on campus.

Jennifer Fasulo, a Spanish teacher at Charles W. Baker High School in Baldwinsville, a Syracuse suburb, was placed on a paid leave of absence on Jan. 30, just weeks after she offered to help students establish a Club America, the high school division of the Charlie Kirk co-founded conservative group, her supporters say.

“The district can confirm that a staff member has been placed on paid administrative leave while a matter is under review. We are following established administrative and legal procedures, and we are unable to comment further or share additional details at this time,” the Baldwinsville Central School informed parents in a Feb. 10 letter.

“We need to go in a socialist direction” to build what he praises elsewhere as a socialist “intellectual apparatus” like the ones in Cuba and China, because that’s where he says you get the “real state power necessary to fully educate the people.”

Archaeologists Unearthed a 2,200-Year-Old Bone. They Say It Could Be the First Direct Evidence of Hannibal’s Legendary War Elephants

which occurred in the third century B.C.E. This conflict was part of the series of wars between Rome and Carthage, an ancient city in modern-day Tunisia.

Study co-author Agustín López Jiménez, an expert at the archaeology company Arqueobética, which excavated the site, told El Pais that researchers found the elephant foot bone beneath some collapsed adobe walls dating to around the third century B.C.E. According to the study, the same area revealed 12 three-pound stone balls, which were “unquestionably artillery projectiles for lithoboloi,” a kind of catapult.

The Second Punic War began after Hannibal attacked Saguntum, a city on the Iberian Peninsula that had allied with Rome. When Carthage refused to withdraw, Rome declared war in 218 B.C.E.

What’s Your American Culture IQ?

Test your knowledge with this WSJ quiz about books, music, movies and more

Madison crowns its top speller, who won bee with ‘drupiferous’ and ‘Ecuador’

The three top spellers advanced to the Badger State Spelling Bee on March 21, so Barnhill will be joined by Joanne Aldoori of Madinah Academy, who placed second, and third-place finisher Ignatius Fassino of St. Ambrose Academy.

Casey Barnhill found his spelling bee victory cradled between Colombia, Peru and the Pacific Ocean. The Velma B. Hamilton Middle School student took first place after correctly spelling “Ecuador.”

Barnhill was one of 41 students vying for the title of Madison’s star speller Saturday at Madison College’s Mitby Theater.

“I’m feeling good because I got second place last year,” he said. “I got out last year on definition.”

The three top spellers advanced to the Badger State Spelling Bee on March 21, so Barnhill will be joined by Joanne Aldoori of Madinah Academy, who placed second, and third-place finisher Ignatius Fassino of St. Ambrose Academy.

———

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

Civics: A Republic, if you can keep it

The conclusion of Justice Gorsuch’s concurrence in the tariff case:

For those who think it important for the Nation to impose more tariffs, I understand that today’s decision will be disappointing. All I can offer them is that most major decisions affecting the rights and responsibilities of the American people (including the duty to pay taxes and tariffs) are funneled through the legislative process for a reason. Yes, legislating can be hard and take time. And, yes, it can be tempting to bypass Congress when some pressing problem

arises. But the deliberative nature of the legislative process was the whole point of its design. Through that process, the Nation can tap the combined wisdom of the people’s elected representatives, not just that of one faction or man. There, deliberation tempers impulse, and compromise hammers

disagreements into workable solutions. And because laws must earn such broad support to survive the legislative process, they tend to endure, allowing ordinary people to plan their lives in ways they cannot when the rules shift from day to day. In all, the legislative process helps ensure each of us has a stake in the laws that govern us and in the Nation’s future. For some today, the weight of those virtues is apparent. For others, it may not seem so obvious. But if history is any guide, the tables will turn and the day will come when those disappointed by today’s result will appreciate the legislative process for the bulwark of liberty it is.

Jeffco Schools’ shell game shuts out charters

In early 2024, Jeffco Schools carved out a special “municipal interest” process enabling Lakewood and other municipalities to bypass traditional bidding to acquire shuttered schools.

Eight months earlier, an appraisal had made it clear to the school district that competitive bidding was in fact viable for the closed Emory Elementary, meaning the district could sell the property and turn a tidy profit for taxpayers within a year.

Disregarding that appraisal, the board of Colorado’s second-largest district voted last November to sell the Emory property to the city of Lakewood for $4 million — without going through a bidding process.

Shortly before that, Lakewood’s city council had approved flipping the closed school to The Action Center, a social and homeless-services nonprofit, for just $1 million, while retaining seven acres of the 17-acre property as open space for the city.

Extractive Taxation and the French Revolution

Tommaso Giommoni, Gabriel Loumeau & Marco Tabellini:

In this paper, we provide systematic evidence in support of the long-standing hypothesis that taxation was an important driver of the French Revolution. We first document that areas with heavier taxes experienced more riots between 1750 and 1789 and voiced more complaints against taxation in the cahiers de doléances of 1789. After showing that these effects are driven by indirect taxes, we exploit sharp spatial differences in the salt tax and the traites—the two principal indirect levies—to implement a regression discontinuity design (RDD).We find that unrest was higher on the high-tax side of the border. These effects intensified over time, peaking in the 1780s, and were stronger where fiscal disparities were larger and Enlightenment ideas more widespread. We further show that adverse weather shocks amplified unrest in high-tax municipalities. We then document that taxation fueled the spread of unrest during the Grande Peur—the wave of revolts that swept France in July 1789 and culminated in the abolition of feudal privileges. Finally, we link taxation to revolutionary politics in Paris, documenting that deputies from heavily taxed constituencies were more likely to frame the tax system as oppressive, support the Revolution, demand the abolition of the monarchy, and vote for the king’s execution.

The growing market for education alternatives

If change is happening in the market for K-12 education, can higher ed be far behind?

The trends noted above work to the benefit of UATX. The families that have explored alternatives to public schools make up the addressable market. If you have already opted out of the normal path of education, then it is not such a leap to try UATX.

Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect UATX to achieve its aggressive growth goals for the next couple of years. While legacy universities face a declining college-age population, declining high school test scores, and obstacles to filling their classrooms with foreign students, UATX expects to enroll 125 or more students this fall, as many as in the first two years’ classes put together. This will feel like an invasion, with a large and somewhat unpredictable impact on the atmosphere and culture here.

This influx will arrive in the context of governance issues that are roiling higher education today. Thomas W. Smith writes,

School debt repayment should be a priority, not deferred

Each year, Wisconsin property taxpayers contribute more than $6.5 billion in local school levies. Those dollars are commonly understood to support classrooms, teachers and student services. In reality, a large — and growing — portion is diverted to debt service, a non-negotiable financial obligation before a single classroom dollar is spent.

In fact, the debt-service share of the local levy continues to grow, not because students are receiving more, but because past borrowing decisions increasingly dictate today’s budgets. Fortunately, at least one school district is showing that a debt free future is possible.

Statewide, nearly 18% of all local school levies — about $1.18 billion each year — are used to service debt. In practical terms, almost one out of every five local school tax dollars is unavailable for instruction or student support because it has already been committed elsewhere. Unfortunately, long-term debt has become a routine feature of school finance rather than an exception.

Looking at debt on a per-student basis makes the impact clearer. Across Wisconsin, districts levy an average of $1,483 per student each year simply to service existing debt. In districts that carry any debt at all — roughly 85% of districts statewide —that figure rises to $1,550 per student, before any money is spent in a classroom.

At the same time, Wisconsin is experiencing sustained enrollment decline, and while per-pupil revenue limits may decline with enrollment, existing district debt does not shrink when enrollment falls. The obligation stays fixed, and the burden shifts. Even if no new debt is added, fewer students are left to carry the same costs.

——-

30 October 2025 Madison School Board approves a $668,000,000 budget for 25,557 “full time equivalent” students.

Sexual Abuse Epidemic in California

Straight to the Point: Sexual Abuse Epidemic in Public Schools

WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT

00:40 “Pass The Trash” Teachers accused of abuse in public schools are quietly moved to other schools

01:23 Sexual Abuse Epidemic in California

02:40 Mandatory Reporting to law enforcement: Compliance is reported to be near zero

03:40 No legal requirement to notify parents of credible allegations of sexual abuse in schools

04:30 Minority and Poor Communities Disproportionately affected

05:30 Elementary School Teacher pleads no contest to lewd acts with children

07:00 No one wants to acknowledge prevalence of abuse in students K-12

07:35 Data estimates 17% of students in K-12 public schools will suffer sexual misconduct by school personnel

09:00 Teachers Unions know there is “widespread non-reporting” of alleged sexual misconduct

——

200 Wisconsin teacher sexual misconduct, grooming cases shielded from public.

More.

California’s New Bill Requires DOJ-Approved 3D Printers That Report on Themselves

As we’ve said before on this blog, when we covered Washington and New York, it doesn’t matter if you’re pro or anti-gun. The state should prosecute people who make illegal thing, not add useless surveillance software on every tool in every classroom, library, and garage in the state. And as you can see, these bills spread – that’s how an small group can push legislation into the entire country. First, Washington proposed theirs, then New York, now California. Once those three states pass a law, that’s 20~25% of the country by GDP/population and thus every manufacturer is forced to comply with a bad decision in order to stay in business. If you’re a maker, educator, or manufacturer anywhere in the US, even outside these states, this is a problem-problem now.

Legislation may change how Baltimore County school board members are chosen

A battle over control of the Baltimore County School Board is flaring in Annapolis, where Democratic lawmakers are clashing over how many members voters should elect and how many the governor should appoint.

“The Quality of Counsel’s Filings Further Deteriorated”

Some excerpts from the long discussion in Parker v. Costco Wholesale Corp., decided in November by Magistrate Judge S. Kate Vaughan (W.D. Wash.), but only recently posted on Westlaw:

The Court identified material misstatements and misrepresentations in those filings, which contained hallucinated case and record citations and legal errors consistent with unverified generative artificial intelligence (“AI”) use and ordered Counsel to show cause as to why sanctions should not issue. The Court outlines its observations before turning to Counsel’s explanations….

Review of Plaintiff’s Response to Defendant’s Motion for Summary Judgment (“MSJ Response”) indicated the filing relied on inapplicable law, misrepresented and misquoted the law and the record, and included a wide array of idiosyncratic citation errors. For brevity, the Court summarizes the most egregious examples….

[Among other things,] Counsel included hallucinated and inaccurate quotes to the record. This was particularly egregious given that he sought to demonstrate a question of material fact precluded summary judgment and attempted to do so by relying on mischaracterized evidence….

Reflecting on The Twin Cities and the Law

This is not a call for refinement or recalibration of immigration enforcement following months of federal occupation in Minneapolis. It is a call to name failure plainly. When ICE’s ordinary operations require protection from law rather than obedience to it, abolition is not a radical slogan but a natural conclusion. The whistle is being sounded in Minneapolis. The question before the legal profession is whether we will hear it, amplify it, and act accordingly, or rush to patch over the cracks before more bodies make structural collapse inevitable.

Notes on Direct Instruction & Alpha School

Here’s my core prediction: Alpha School will not be the place where we finally unveil the holy grail of education technology, where 100 percent of students can learn from a computer. Alpha School will not be the place where Engelmann’s ideas scale to reach every student. Developing curriculum is an empirical science. Designing great curriculum requires endless tinkering and testing and revision. If that testing happens at a $40,000-a-year private school, it simply will not scale to everyone. Alpha School might do great things for a slice of students. That’s cool. But let’s make sure the claims are in line with reality.1

If Alpha School is serious about being “the future of education,” the solution is simple. I’m seeing these allusions to Engelmann. Follow in his footsteps. Partner with a struggling school where outcomes are poor. Test the curriculum there. Refine and iterate with the students who are most likely to struggle. If Alpha School isn’t interested in doing that, I’m not going to pay much attention to the big claims. Go be a successful private school. Live and let live. I’ll head back to my classroom to do the best I can with boring traditional whole-class instruction.

I’ll note that there’s a section of the edtech world that is honest and straightforward that their products are designed to help the most academically capable students. I appreciate that! I know public schools struggle to challenge talented students, I see it every day. I’m happy those products exist. I respect them for being honest about who they’re designed for. If Alpha School marketed themselves that way, I wouldn’t be writing long posts about all this.

Seeking ongoing k-12 Redistributed state taxpayer fund increases

- A group of 11 Wisconsin school district superintendents is urging lawmakers to increase school funding.

- The superintendents want the state to use its projected $2.5 billion surplus to boost aid and provide property tax relief.

- Districts have faced budget shortfalls, leading to cost-cutting, potential school closures and a reliance on voter-approved referendums.

- Negotiations between Democratic Gov. Tony Evers and Republican legislative leaders over a tax relief package remain at a stalemate.

A group of Wisconsin school district leaders is pleading with lawmakers to increase school funding and provide property tax relief before this year’s legislative session ends.

The superintendents, representing 11 school districts, including Wisconsin’s five largest and six rural districts, said lawmakers should use the state’s proposed $2.5 billion surplus to boost aid to schools. They said rising costs and stagnant state support have forced districts to rely on voter-approved property tax referendums to help meet budget shortfalls.

“Wisconsin urgently needs a bipartisan compromise on school funding,” the district leaders said. “The current stalemate leaves public school districts unable to plan responsibly and pushes local communities to shoulder costs that the state should be sharing.”

Superintendents of the state’s largest districts in Milwaukee, Madison, Kenosha, Racine and Green Bay penned the open letter to lawmakers in late January. District leaders in rural Baraboo, Reedsburg, River Valley, Sauk Prairie, Weston and Wisconsin Dells released the same statement Feb. 17.

——-

30 October 2025 Madison School Board approves a $668,000,000 budget for 25,557 “full time equivalent” students. A bit more than $26k per student.

Madison School Board vice president charged two months after arrest

The Dane County district attorney filed misdemeanor charges of disorderly conduct and resisting an officer against Madison School Board Vice President Maia Pearson Thursday.

The charges stem from a December incident involving Pearson and Brandi Grayson, the CEO of Urban Triage, that led to their arrests. Both Pearson and Grayson have entered not guilty pleas and obtained signature bonds, court records show.

While Grayson had been arrested in December by Madison police on three counts of disorderly conduct and OWI, Grayson was only chargedThursday with disorderly conduct and resisting an officer.

Pearson and her lawyer didn’t immediately respond to requests for comment, nor did Grayson’s attorney.

In a separate pending case, Grayson is facing disorderly conduct and property damage chargesthat followed a report by a man she had previously been in a relationship with. Grayson has pleaded not guilty in that case, as well.

———

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

Yet another Madison Math Curriculum….

After screening bids to ensure the materials met mandatory requirements, the school district’s K8 Math Leadership team sent along four proposals for further consideration by a larger selection committee.

That committee included 40 people across 21 schools and the district’s central office, as well as School Board member Ali Muldrow and Lisa Hennessey, a University of Wisconsin-Madison teaching faculty member who serves on the board of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Following hours of meetings and evaluations in January, the committee selected Illustrative from three finalists. The cost estimates for Illustrative or the other finalists weren’t shared in materials provided at the Instruction Working Group meeting this month. District administrators previously told School Board members the price tag of math materials would be less than its most recent purchase of reading curriculum, which cost $5.6 million.

In a presentation to School Board members, district officials highlighted the curriculum’s approach to working with students of different skill levels. Madison high schools already use Illustrative materials, meaning there would be consistency if the curriculum is adopted across all grade levels.

District officials particularly emphasized Illustrative’s “problem-based” learning approach, which involves students first tackling problems in small groups and then trying it themselves with supervision before the teacher models how to solve the problem.

—-

“The commercial math-education sector is flooded with ineffective math programs and T professional development marketed as “research-based.” But that can mean almost anything, from small case studies to opinion framed as research.”

——-

2014: 21% of University of Wisconsin System Freshman Require Remedial Math

How One Woman Rewrote Math in Corvallis

Singapore Math

Discovery Math

Math Forum 2007

Thoreau Elementary Student Nude Photo Case

Jensen then told police that the person who made the original report in October has a stepsister who goes to Thoreau, that the stepsister had seen the photo and told her mother about it, and that the mother had reported the photo’s existence to the school.

Madison police and the Madison School District launched investigations after the staffer at Thoreau Elementary School allegedly took the photo of the then-7-year-old, developmentally disabled boy in late September.

In response to a Feb. 13 Wisconsin State Journal story about the matter, Thoreau Principal Emily Jensen sent a message to Thoreau families Thursday asserting that while the photo’s existence was reported to the school on Oct. 1, police who followed up on the matter did not share the photo with the school.

——-

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

Indiana University funneled $25M directly to athletics last year

Some of those funds come in the form of utility bills and facilities maintenance but the vast majority – $25 million – came in direct transfers of unrestricted university funds: money that can otherwise be used anywhere at IU.

It’s the second highest year on record, after appropriating $34.3 million in 2024 to close the deficit – more than eight times the average for other Big Ten schools.

But in the 2025 fiscal year, IU athletics reported a $10 million surplus, driven mainly by media rights, ticket sales and contributions. That’s according to IU’s NCAA financial report, obtained Monday by WFIU.

None of IU’s direct support was returned to the university, per the report.

Adjusted for student poverty, southern states are beating the rest

It helps that red states have gone back to basics: legislators in state capitals have enacted new rules that require teaching reading via phonics and holding failing schools accountable. Those decisions matter a great deal for classrooms. But America is made up of more than 13,000 school districts, most of which have the autonomy to set policy, too. That gives cities and towns across the country the opportunity to run small experiments to figure out how to get students to learn—and then to double down on what works.

In Birmingham, Alabama, city leaders are doing just that. This is not a place where fixes come easily. Pupils in the school district are almost all black and nine out of ten qualify for free or cut-price lunches. For years their test scores were a drag on state averages (which were already low). But a few clever policies seem to be turning things around.

In the past two years the city went from having 15 “F”-rated schools to just one. A Stanford and Harvard study found that children in Birmingham are making up for maths learning lost during covid lockdowns about half a grade level faster than students in less poor districts. Kay Ivey, Alabama’s Republican governor, boasted in her state-of-the-state address last February that Alabama is no longer “just a football state” but also an “education state”.

———

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

Why 69 Wisconsin schools have closed in the past two years. More could follow.

Declining enrollment is a big reason behind school closures

Shaw said that while the Policy Forum has not specifically studied school closures, it has closely tracked student enrollment, which has a direct effect on funding.

Enrollment has declined at public school districts every year for more than a decade. That decline has affected a majority of Wisconsin school districts, Shaw said.

Statewide, public school enrollment in the 2014-15 school year was 870,652. By 2024-25, that had dropped to 805,881, according to the Policy Forum, a decline of almost 65,000 students – more than 7% statewide.

The main factor: a decline in the birth rate statewide.

———

Choose life.

———

“Statewide, public school enrollment in the 2014-15 school year was 870,652. By 2024-25, that had dropped to 805,881, according to the Policy Forum, a decline of almost 65,000 students – more than 7% statewide.”

Stop conflating success with moral authority

“What if the valedictorians in America’s schools were the cool kids?” This is the question Nicholas Kristof posed in his recent column in The New York Times, imagining a culture in the U.S. where academic excellence carries the same social prestige as it does in some East Asian countries.

But in many of the environments I’ve inhabited—elite universities and professional circles in New York, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.—the valedictorians are already the cool kids. Whether they exhibit genuine academic prowess or have learned to “game the system,” their presumed competence is the ultimate social currency. It grants them not just admiration, but often a kind of anticipatory deference based on the influence they will presumably wield in the future.

Mr. Kristof is not necessarily wrong or alone in feeling envious of the high regard that some prosperous, rapidly developing democracies, particularly in Asia, have for education. Exploring the role cultural values play in shaping national outcomes has preoccupied educators and institutional leaders for decades. And at a time when gifted programs and test-entry schools are falling out of favor in much of the U.S., his point is especially well taken.

But I worry that we have come to conflate intelligence and success with moral authority.

In America’s high-achievement settings, excellence can function as a form of psychological and social insulation: Intelligence is taken as a proxy for virtue; success as evidence of character and wisdom. Over time, this dynamic can make it harder for the most credentialed and celebrated individuals to question their own judgment or remain open to new viewpoints. It can also make it harder for others to question the behavior of those whose accomplishments appear to place them beyond reproach.

College attendance isn’t explained by intelligence or conscientiousness signaling

A key problem with Caplan’s trinity is that most of it is easily replaceable. Getting good grades at college does signal intelligence and conscientiousness, but these could be signaled far more easily and cheaply. It’s very easy to signal intelligence via test scores: IQ is surprisingly predictive of many other desirable cognitive traits. This need not require literal IQ tests—standardized tests like the SAT or GRE are highly correlated with intelligence. In other cases, companies use IQ-like tests (e.g. tech companies’ coding interviews). These are also significantly harder to cheat on than college courses.

Caplan acknowledges that college grades are far from the best way to signal intelligence; what he doesn’t discuss is that they’re even further from the best way to signal conscientiousness. If you asked people why they don’t just learn college material independently without paying for college, I expect that a common response would simply be “oh, I don’t have the discipline for that”. College provides external frameworks, timetables, local incentives, and social pressure for people who aren’t conscientious enough to learn without that.

Stop Pushing College for All

Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral win in New York City was a warning of what could lie ahead in American electoral politics—especially the enthusiasm that he inspired among younger voters. Those aged 18–29 had the highest turnout of any group, at 35 percent, almost double its level in 2021. Mamdani’s democratic socialist agenda also draws support beyond New York. An Axios/Generation Lab poll conducted days before the mayoral election found that 67 percent of college students held a positive or neutral view of socialism; only 40 percent said the same about capitalism.

Support for socialism and for figures like Mamdaniprimarily comes from young people who feel priced out of the American dream—owning a home, securing a stable job, and starting a family. Many first confront the gap between expectation and reality when they enter college and take on substantial debt, a stark contrast with the youthful freedom that older Americans often associate with their own college years.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

On college affordability, Democrats have built brand trust: voters expect subsidies from them. The issue is salient enough that even local politicians like Mamdani, who have relatively little jurisdiction over higher-education policy, feel compelled to voice broadcommitments to boosting university subsidies.

The national pattern: gentrify, then opt out

There’s a pretty robust body of research on what happens to schools when neighborhoods gentrify, and the general finding is: not much. Or rather, not the thing you’d naively expect.

A Stanford study by F. Chris Pearman found that gentrification was actually associated with declining enrollment at neighborhood schools, with the largest drops occurring when the gentrifiers were white. In Denver, gentrifying neighborhoods saw a 23% enrollment decline between 2006 and 2016 as white families used school choice mechanisms — charters, magnets, out-of-boundary transfers — to avoid their zoned schools. A Chalkbeat analysis found that in gentrifying areas nationally, white parents enrolled their kids in schools with 19% fewer poor students and 14% fewer Black and Hispanic students than their assigned neighborhood school.

The basic dynamic is straightforward and kind of depressing: white families move in, housing prices rise, the neighborhood changes, but the schools don’t. Or they change only in the sense that lower-income families get priced out and enrollment declines.

New York City is the partial exception, where gentrifying schools saw a 40% increase in white enrollment between 2000 and 2014. But even in New York, that was concentrated in specific neighborhoods — it wasn’t a district-wide transformation.

k-12 Tax & $pending Climate: Seattle’s gig worker law was supposed to boost pay. It did at first, until orders dropped

Things slowed down. Orders weren’t coming in; they still aren’t coming in like they used to. One worker told me she can be logged on for hours without receiving an order. Customers still want the convenience, but many balked at the fees that the apps tacked on after the new law. The companies say the fees are necessary.

That pattern is consistent with a recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research —wages were higher in the first few months and then dropped. The study also found that months later, drivers have more unpaid idle time, and drive longer distances between orders.

And how about local businesses, how has the law affected them?

I checked back with Uttam Mukherjee, co-owner of Spice Waala, that serves Indian street food on Capitol Hill, Columbia City, and Ballard. Mukherjee has expressed concerns early on. Those concerns he says have become real — he’s getting fewer orders coming through those apps because of the added fees that customers are now paying.

The Missing “One-Offs”: The Hidden Supply of High-Achieving, Low-Income Students

Caroline Hoxby & Christopher Avery:

We show that the vast majority of low-income high achievers do not apply to any selective college. This is despite the fact that selective institutions typically cost them less, owing to generous financial aid, than the two-year and nonselective four-year institutions to which they actually apply.

Moreover, low-income high achievers have no reason to believe they will fail at selective institutions since those who do apply are admitted and graduate at high rates. We demonstrate that low-income high achievers’ application behavior differs greatly from that of their high-income counterparts with similar achievement. The latter generally follow experts’ advice to apply to several “peer,” a few “reach,” and a couple of “safety” colleges. We separate low-income high achievers into those whose application behavior is similar to that of their high-income counterparts (“achievement-typical”) and those who apply to no selective institutions (“income-typical”). We show that income-typical students are not more disadvantaged than the achievement typical students. However, in contrast to the achievement-typical students, income-typical students come from districts too small to support selective public high schools, are not in a critical mass of fellow high achievers, and are unlikely to encounter a teacher who attended a selective college.

We demonstrate that widely used policies—college admissions recruiting, campus visits, college mentoring programs—are likely to be ineffective with income-typical students. We suggest that effective policies must depend less on geographic concentration of high achievers.

Don’t fear the AI ‘jobpocalypse’

We can see that the drop in vacancies predates the release of OpenAI’s large language model (LLM). Instead, the fall in job postings dovetails with a period in which the Federal Reserve pressed the brakes on the US economy by raising interest rates by 5 percentage points.

What’s more, because of the post-pandemic surge in openings and hiring, the subsequent reduction appears to reflect a normalisation.

These broad trends in hiring and central bank rate increases hold in many G7 nations during the same period.

There are non-AI drivers of labour market weakness, too. For instance, in Britain the rise in youth unemployment is, in part, linked to the Labour government’s policies, such as payroll tax increases.

She Graduated With Honors But She Can’t Read

I sometimes wonder about the fervor education bureaucrats have for making standardized testing optional. Then I hear stories like Aleysha’s and know exactly why they do it. Tests reveal the rot.

San Francisco paid 6-figures to education school bureaurcrats pushing “Grading for Equity” — homework doesn’t count, unlimited test retakes, lateness and absence don’t affect grades. A score of 80 can earn an A. The game is to keep grades up while learning collapses. Rubber stamp F’s into C’s, C’s into B’s, B’s into A’s.

And once you’re through the gate? Harvard doesn’t even offer remedial writing courses. There’s nowhere to catch up. The students who were passed through without learning are stranded.

———

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

k-12 Tax & $pending climate: Administrative growth amidst declining enrollment

Since 2000, for every eight students lost, public schools added one non‑instructional staff member.

More adults than ever, yet fewer kids reading and doing math at grade level. That’s not a ‘year of the kid’ – that’s decades of growing a bloated bureaucracy.

———

New York City has an unusually high per capita spending level.

When you have a good point, make it the right way.

Notes on Race based lunch programs at Madison’s Blackhawk Middle School

Dan O’Donnell, via a kind reader:

Black Hawk Middle School in Madison, Wis. is openly violating the 14th Amendment, Civil Rights Act, and years of Supreme Court precedent by offering free brunch and games today to only black students and staff members.

New York’s Class-Size Law is Wreaking Havoc

In September 2022, Governor Kathy Hochul signedS960, a bill limiting the size of classes in New York City public schools. The law phases in class-size limits—20 students for grades K–3; 23 students for grades 4–8; and 25 students for high school—over six years.

Fast forward to today: the implementation of the class-size law is causing predictable disruptions in Gotham. Parents and experts warned from the beginning that the law would be expensive, hard to implement, and generate, rather than reduce, inequality. Three years in, their fears remain valid.

Smaller class sizes mean more classes—and more teachers. New York City’s Independent Budget Office (IBO) estimated that the new law would cost the city between $1.6 billion and $1.9 billion annually to hire the number of additional instructors required to comply with the law. This would make the city’s public schools, already projected to spend more than $42,000 per pupil, even more inefficient.

The College Board has politicized and watered down its AP exams. It’s time for an alternative.

At its founding in 1956, the AP program was not intended to be such a behemoth. Its founders viewed it as “an opportunity and a challenge to … the strongest and most ambitious boys and girls.” For the program’s first several decades, its growth reflected that purpose. In 1956, 2,199 AP exams were administered nationwide. That number increased by an average of 10,567 tests per year over the next 30 years. By the pandemic’s aftermath, growth had accelerated to an average of 325,000 additional tests administered per year, reaching 6.25 million in 2025.

Amidst this blitz, the New York Times asked, in a 2023 article, “Why Is the College Board Pushing to Expand Advanced Placement?” The story noted that, “for the past two decades, the College Board has moved aggressively to expand the number of high school students taking Advanced Placement courses and tests—in part by pitching the program to low-income students and the schools that serve them. It is a matter of equity, they argue.”

That move was so successful that the Times said the AP program had become “something of a de facto national curriculum.” Indeed, the financial success of the AP program is matched only by its power over American classrooms.

Civics: With Chevron gone, states must finish the job on judicial deference

Across the country, a quiet but important shift is underway in how courts review administrative agency decisions. Nineteen states have ended judicial deference to administrative agencies (including Kansas just this week), either through legislation or state court decisions. More are poised to follow. Bills are currently pending in states like Alabama, South Carolina, South Dakota, and West Virginia, reflecting a growing recognition that judicial deference undermines the rule of law and tilts the scales of justice too far in the government’s favor.

That momentum accelerated in 2024, when the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Chevron deference in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo. For four decades, Chevron required federal judges to defer to an agency’s interpretation of the laws it administers whenever statutory language was deemed ambiguous. Rather than weighing competing interpretations and choosing the most persuasive one, Chevron mandated that judges put a thumb on the scale for the government.

The results were predictable. Chevron led to a dramatic win rate for federal agencies—often at the expense of individuals, small businesses, and regulated entities that found themselves in the crosshairs of government enforcement. By overruling Chevron, the Court reaffirmed a basic constitutional principle: it is the judiciary’s job to say what the law is.

ButLoper Brightresolved only half the problem. While federal courts are no longer bound byChevron, many states continue to apply their own versions of judicial deference. In those states, agencies still enjoy a built-in advantage when their interpretations of state law are challenged. As a result, Americans’ rights can vary dramatically depending on whether a dispute arises under federal or state law—and depending on which state they live in.

The Great Books teach your mind to free solo

The purpose of education is to help us live better lives.

Rebecca and Henry have asked me to write something for this blog about liberal education. What is a liberal education, they ask? Why does the “Great Books” stuff I’ve been doing as a teacher for the past few years, they ask, fit the model? My former Tulsa Honors colleague Dan Walden just came out with an essay about these topics in The Point, too. I largely agree with Dan, but with some differences of emphasis.

I think an appropriate liberal education is one that teaches us to “free solo,” intellectually speaking. The deepest, most difficult questions that arise in our lives stare us down like barren rock walls, unmarked and unscalable, pristine in a precipitous terror of sand. To live thoughtfully, reasonably, and morally is no small task, let alone to do so freely and authentically. Yet this is what our very ability to think and act seems to demand of us – at least to some of us, the way a mountain might demand to a free soloist to be climbed. Through a liberal education, free people grow in their capabilities, their powers, until few things accessible to their reason and will remain foreign to them.

Los Angeles Is the Next Target in California’s Teacher Strike-Threat Campaign

Douglas Berlin & Scott Calvert:

By coordinating negotiations across the state with the threat of strikes, the unions aim to escalate funding battles from local school boards to the state legislature, said David Goldberg, president of the California Teachers Association, a union representing more than 300,000 educators. The state contributes a majority of the money in public K-12 school budgets.

Democrats, This Is Why You Haven’t Fixed Schools Yet

America is in a decade-long education depression. Barely a third of students are proficient in reading or math across most grades in recent testing, achievement gaps are widening fast, and too many college freshmen are arriving on campus unable to read a full book or do middle-school-level math. Chronic absenteeism has surged after the pandemic; students are disengaged. Educators are burning out, and teachers are increasingly hard to recruit and retain. Costs are rising. Trust in public schools is at a record low, and families with the means to leave increasingly do, leaving districts with half-empty buildings.

This is what an institutional breaking point looks like. In these periods of deep political and social change, or interregnums, reforms that were once considered unthinkable become not only possible but also necessary. This moment of crisis in K-12 education is an opportunity to reimagine it from the ground up. We need nothing less than a new educational operating system — one that channels public funding through students and families directly, rather than through centralized district bureaucracies.

For decades, reformers have tried to fix the education system from within, pushing for higher standards, better data, stronger accountability and more equitable funding. Some gains have been made, but efforts to improve the system have repeatedly ground to a halt, blocked by bureaucratic inertia and political gridlock.

At the heart of this resistance is a fundamental misalignment of incentives. Schools are largely funded according to their ZIP code, not their success or failure. They often don’t need to deliver strong outcomes to maintain enrollment or secure their budgets. Without structural incentives to improve, even well-meaning systems stagnate, as bureaucracies optimize for self-preservation rather than delivering results. To transform our education system, we need to change the architecture of the system itself, not just patch the policies and programs that sit on top of it.

——-

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

UCLA’s Head of Finance Alleged Years of Mismanagement. Days Later, He Was Fired.

Days after alleging years of financial mismanagement in an interview with the student newspaper, the chief financial officer of the University of California at Los Angeles is out of a job.

Stephen Agostini, who started at UCLA in 2024 after serving as the associate vice chancellor for finance and budget at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, was fired, according to a university spokesman. Tuesday’s

——-

The abrupt change came days after Agostini gave an interview to the Daily Bruin student newspaper saying the campus had “financial management flaws and failures” predating his arrival, leading to what he said was a $425-million deficit. In the interview, Agostini blamed financial woes on faculty and staff raises, academic departments’ requests for new positions and expanded programs, and UCLA athletics, which has run in the red for multiple years.

Agostini suggested that UCLA’s annual financial reports going back to 2002 were incorrect, saying he saw “very serious errors” — a charge UCLA officials deny. UCLA’s last posted financial report covers the 2022-23 fiscal year.

———

Financial mismanagement contributed to $425 million annual deficit, UCLA CFO says

k-12 tax & $pending climate: Chicago’s declining economic base

Just look at the numbers on this list. It’s staggering.

This is what depression level pricing looks like! Does Mayor Johnson know what this does to residential property taxes to fill the gap in the levy?

Doubtful he does.

Small wonder there has been a $2B property tax shift from commercial to residential property since 2021.

Does the mayor know what the depopulating of the downtown does to retail and service industries?

How about Chicago’s 9000 restaurants that he has saddled with new costly mandates?

Trick question. Of course he doesn’t.

——-

35,364 fewer students.

6,343 more staff.

Still not “fully funded.”

———

Real per capita federal spending:

2026: $22,550

2000: $12,915

Even adjusting for inflation and population, federal spending is up 75%.

Gen Z Men & Highly Educated Lead Return to Religion

By Joel Kotkin & Bheki Mahlobo,

The decline of religion remains a fundamental reality in most Western countries, particularly in Europe, where over 50% of those under age 40 do not identify with any faith. Even in more religious America, some estimate that as many as 100,000 churches will close in the near future. Meanwhile, the ranks of “Nones,” those outside religious communities, have grown so large that their numbers rival those of Catholics and evangelical Protestants.

Yet, as we document in a new report for the Chapman Center for Demographics and Policy, there are signs that religion is enjoying more than a nascent revival. Data emerging from the 2020s suggest that we are witnessing a complex spiritual restructuring that intersects with economic mobility, demographic resilience, and a profound intellectual realignment.

For the first time in decades, Pew Research notes, in the U.S. at least, Christianity has stopped its nosedive as more people begin to see the efficacy, and the rewards, of religious faith and practice.

This fragile development is especially noteworthy as it exposes growing divides and fault lines in American politics and culture. Drawing on a vast array of longitudinal studies, interviews, and other sources, one startling finding in both America and abroad is that, contrary to past assertions, today the faithful are not poor and ignorant but increasingly from the educated upper middle class.

How generative and agentic AI shift concern from technical debt to cognitive debt

The term technical debt is often used to refer to the accumulation of design or implementation choices that later make the software harder and more costly to understand, modify, or extend over time. Technical debt nicely captures that “human understanding” also matters, but the words “technical debt” conjure up the notion that the accrued debt is a property of the code and effort needs to be spent on removing that debt from code.

Cognitive debt, a term gaining traction recently, instead communicates the notion that the debt compounded from going fast lives in the brains of the developers and affects their lived experiences and abilities to “go fast” or to make changes. Even if AI agents produce code that could be easy to understand, the humans involved may have simply lost the plot and may not understand what the program is supposed to do, how their intentions were implemented, or how to possibly change it.

Technical debt lives in the code; cognitive debt lives in developers’ minds.

I’ve experienced this myself on some of my more ambitious vibe-code-adjacent projects. I’ve been experimenting with prompting entire new features into existence without reviewing their implementations and, while it works surprisingly well, I’ve found myself getting lost in my own projects.

civics: “secret courts” and the censorship industrial complex

The American people need to have confidence in the people tasked to serve as amici before the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court,” Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Chuck Grassley (R., Iowa) told the Washington Free Beacon about Daskal’s selection.

He highlighted a bill he sponsors, the FISA Accountability Act, which would give Congress a role in selecting amici curiae for the court. Currently, the presiding judge of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court and the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review appoint amici. Those roles are held by district court judge Anthony Trenga, a Bush appointee, and Stephen Higginson, an Obama appointee to U.S. circuit judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

Sen. Eric Schmitt (Mo.), another Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, grilled Daskal about her disinformation board background at a hearing on May 20.

How One Professor Helped Kill a Bad Bill

Jelani Nelson drove to Sacramento for months, recruited allies, and won: Academic standards at UCs matter

“Show up. Shock them out of their comfort zones. Let them know business as usual is over,” Nelson wrote. “Politics is a repeated game, and we are establishing a new equilibrium.”

Legislative bill season is here again. Nelson reports no new dumbing-down bills yet — knock on wood. That’s not luck. That’s the result of politicians understanding there’s organized opposition watching every move.

This is how you win. Not with one angry tweet. Not with one testimony. You show up again and again until they understand: every vote is being watched. Every bill is being tracked. The education bureaucrats thought they could quietly dismantle standards while no one paid attention. Now they know better.

America Needs a Better Meritocracy

Meritocracy is like free trade. Countries or classes embrace it when it advantages them and view it more skeptically when they are no longer on top. Like Great Britain before us, America preached free trade when it meant opening up foreign markets to our world-beating products and enriching our allies. When it came to mean losing our industrial base to China, we belatedly started to ask whether the case for free trade was really so axiomatic.

“Meritocracy is like free trade.”

The same pattern is now playing out with meritocracy. It was a useful rallying cry for those who wanted to open up America’s ruling institutions to non-WASPs, starting with the Ivy League in the 1960s and culminating when the new class swept through Washington in the Clinton years. But when it came time for those newly minted elites to send their own children to college, suddenly unfettered dynamism no longer looked so appealing. A wave of books appeared in the 2010s with titles such as The Meritocracy Trap, The Tyranny of the Meritocracy, and Twilight of the Elites: America after Meritocracy.

This belated skepticism was doubtless self-serving. But, like the free-trade skeptics, meritocracy’s critics were right. Free trade and meritocracy are both ways of maximizing competition; competition is healthy, but too much can be toxic.

K-12 Tax & $pending climate; “What does Chicago’s treasurer do, exactly? And why is it elected?”

Austin Berg:

The answers reveal how a hollow office wreaks havoc on the health of Chicago’s finances.

Chicago’s treasurer

The city’s current treasurer has made herself unusually vulnerable to criticism. Melissa Conyears-Ervin has been the subject of multiple ethics investigations and scandals since taking office in 2019.

Here are the toplines:

- Security detail controversy: Conyears-Ervin briefly received a Chicago police security detail upon taking office. After a security assessment concluded neither the treasurer nor the city clerk required ongoing police protection, CPD withdrew that detail. Conyears-Ervin then hired private security guards using public funds. No previous Chicago treasurer is known to have received a CPD security detail. The controversy resurfaced in 2024 when Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson attempted to bankroll the treasurer’s security team using the city’s water fund.

- Asking banks for personal help: While overseeing deposits of city funds with BMO Harris and other banks, Conyears-Ervin acknowledged asking BMO to provide a loan to her husband’s landlord. Two former employees alleged she tried to “force” the bank to issue a mortgage on the building that houses the aldermanic office of Conyears-Ervin’s husband, 28th Ward Ald. Jason Ervin, who also serves as Johnson’s hand-picked chairman of the Budget Committee.

- Repeated ethics violations: The Chicago Board of Ethics found in April 2024 that Conyears-Ervin committed 12 violations of the city’s Governmental Ethics Ordinance and moved to impose $60,000 in fines. In a separate probe, involving misuse of city resources and the firing of whistleblowers, she agreed to a $30,000 settlement to resolve those charges.

A student built a matchmaking algorithm….

More than 5,000 Stanford students have used Date Drop at a school with about 7,500 undergraduates. It has spread to 10 other colleges including Columbia, Princeton and MIT, and Date Drop just raised $2.1 million in venture-capital funding.

The growth, fans say, reflects a reality about many college kids: They’re intimidated by real-life courtship and overwhelmed by the endless scroll of dating apps. Entrepreneurial students have found huge demand for alternate matchmaking tools.

“It helps people take a chance on connection,” said Weng, a computer-science student who coded Date Drop in about three weeks. “You get a reason to meet up with a specific person, take some of that pressure off.”

Massachusetts father cannot opt his kindergartner out of books about ‘gender stereotypes’

The lawsuit includes children books that depicts gay and lesbian couples with children, including the book “Families, Families, Families!” (Federal filing screenshot)

Massachusetts father cannot opt his kindergartner out of books about ‘gender stereotypes,’ federal judge rules: ‘It does not violate plaintiff’s religious faith’

Georgia House passes bill allowing high school athletes to profit from NIL deals

Atlanta News First staff and Abby Kousouris

A bill advancing at the state capitol could significantly change high school sports across Georgia.

It would allow student-athletes to earn money from their name, image and likeness, or NIL.

House Bill 383, known as the Georgia High School NIL Protection Act, passed unanimously out of the House Education Policy and Innovation Subcommittee on Tuesday.

Supporters say the legislation would place guardrails around a system that already exists, while critics warn it could expose young athletes to pressure and exploitation.

Notes on Notre Dame

The central problem at Notre Dame is that these fine words are not acted upon in a remotely consistent and thoroughgoing manner. Various programs, centers, and institutes scattered across campus, and a certain number of individual faculty members, do work hard to engage the Catholic intellectual tradition. But at the institutional level, with the university as a whole, Notre Dame’s leaders are equivocal about that Catholic mission and make decisions and pursue practices that undermine it.

Compared to most other places, Notre Dame has many good things going on. But compared to what it could and should be—what it says it wants to be—Notre Dame is a disappointment. It’s not just that the university hasn’t reached its potential, it’s that it hasn’t seriously tried. Sustained engagement with the Catholic intellectual tradition happens in pockets, but leaders avoid the institutional efforts that would make this engagement consistent and integrated.

What might such efforts look like? To begin with, Notre Dame’s leaders should be consistently clear and vocal about the purposes and entailments of a university with a Catholic mission. Department chairs and deans should understand and support that mission by being intentional and careful in recruiting faculty who understand (or are willing to learn about) the mission of a Catholic university and can in good faith commit to supporting it in their own ways.

More.

Wisconsin school spending exceeds pre-Act 10 levels even after inflation – Badger Institute

Per-pupil spending by Wisconsin school districts is at its highest level since 2000 even after adjusting for inflation, according to data from the Department of Public Instruction.

Statewide, school districts spent $17,400 per student in the 2023-2024 school year, more than $1,000 higher than the previous year.

Total education cost per pupil — the red line on the graph — has risen steadily except for a two-year dip following the 2011 Act 10 labor reforms, which permitted districts to reduce employee benefits costs. Growth accelerated in 2021 following the COVID pandemic.

Adjusted for inflation — the blue line — per-pupil spending now exceeds its prior peak in 2010, when per-pupil spending was equivalent to $17,386 per student in today’s dollars.

——-

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average k-12 $pending, now around $26,000 per student.

I’m a Harvard Student. It’s Too Easy to Get an A.

am a senior at Harvard. Last week, a faculty committee released a proposal to combat grade inflation at my school. The proposal would do two things: First, it would cap the number of A grades issued to undergraduates at 20 percent for every class. Second, Harvard would cease using grade point average (GPA) to rank students for academic honors and prizes and instead turn to average percentile rank—a measure of how students perform relative to their classmates. If passed by a full faculty vote later this spring, the proposal would take effect in the 2026–27 academic year.

How do the students feel about this proposal? You will perhaps not be surprised to hear they are up in arms. While faculty, according to the campus paper, lent cautious support to the initiative, an overwhelming 84.9 percent of my peers “definitely” disagree with limiting A grades to 20 percent, according to a Harvard Undergraduate Association survey.

I’m among the minority who support the proposal. Let me explain why.

Making the War Colleges Great Again