Corey DeAngelis summary:

The nation’s largest teachers union adopted a business item “to defend against Trump’s embrace of fascism by using the term facism [sic] in NEA materials correctly characterize Donald Trump’s program and actions.”

Corey DeAngelis summary:

The nation’s largest teachers union adopted a business item “to defend against Trump’s embrace of fascism by using the term facism [sic] in NEA materials correctly characterize Donald Trump’s program and actions.”

The employer contribution strikes me as important. Suppose that in addition to the initial $1000 government payment that on average $1000 is added per year for 18 years (by a combination of parent and parent employer contributions). Note that this is below the maximum allowed annual contribution of $5000. At a historically reasonable 7% rate of return these accounts will be worth ~36k at age 18, $58k at age 25 and $875k at age 65 subject to uncertainty of course as indicated below.

Our fictional monk Godwin lived in the wake of the single most significant event in the history of the English language: the Norman Conquest of 1066.

Before the Conquest, English — albeit an old form of English — was the language of power and government in England. After the Conquest, French took its place for centuries.

It was but a temporary replacement: English eventually re-established itself in the halls of power, thanks to the gradual loss of English territory in France and the birth of a new English identity during the Renaissance. But the period of French dominance left its mark on all aspects of the language, from vocabulary to pronunciation. And, as Godwin found to his chagrin, it had a revolutionary impact on English spelling.

In fact, this early French influence over English, which arose from the Norman Conquest, is the beginning of the reason why English is written without accent marks (é, à, ç, etc.), or, as linguists call them, diacritics, today.

Let’s keep calling them diacritics, since accent can mean so many things, from different regional ways of speaking to where in a word you place the emphasis.

Young people typically start out on the political left but become more conservative as they get older. Baby boomers who once marched against the Vietnam war got jobs, got married and had children. Now their grandchildren see them as tethered to Fox News.

Today’s young Americans are following the first part of that pattern. Ask a group of them to choose between capitalism and socialism and they will split right down the middle. Their support was crucial in nominating Zohran Mamdani, who says he wants to capture “the means of production,” as the Democratic candidate for mayor of New York.

But will the young people outgrow their radicalism? There is reason to doubt. Record numbers of Generation Z are pursuing higher education, with 53% of those 18 to 24 having completed at least some college. That’s a troubling sign given how left-wing ideology has come to dominate higher ed.

College is where many young people learn that socialism means free stuff. They are indoctrinated to blame capitalism for racism, inequality and climate change. Unlike the older generations, they grew up after the end of the Cold War and have no memory of the atrocities committed by the Soviet Union, Maoist China and other socialist regimes. Maybe they’ll see socialism in action in New York.

Peña is a self-professed radical who boasts of how she wants to dismantle the university from within & lays out an overtly ideological research agenda.

Colleges have always had radical faculty. What’s notable is Peña’s history of lavish funding and awards, including:

—the Johns Hopkins University African Diaspora Studies Postdoctoral Fellowship

—Future of Minority Studies Fellowship

—research support from the Ford Foundation

—research support from the Mellon Foundation

—the 2022 Angela Davis Prize for Public Scholarship

—a 2017 MIT Disobedience Award

List goes on. It’s no accident that we have so many faculty so out of line with the country. Huge and very intentionally craft career incentives brought us here.

David Friedberg’s recent All-In podcast argument sounds convincing: student debt creates desperate graduates, financial stress drives political radicalism, and young Americans embrace socialism because capitalism failed them economically. The analysis captures real and understandable pain but overlooks the underlying mechanisms.

Zohran Mamdani reportedly owes at least $200,000 from his college years. He studied African Studies and graduated without a job, but now he’s winning elections as a socialist candidate in New York City. Friedberg connects the financial dots, but the ideological picture remains invisible.

The consequences have been serious. Parents said principals are retracting previous assurances that they could enroll their children late, and there has been little flexibility with children with special circumstances. At least two families have been reported to the city’s child welfare agency for truancy because they did not send their 5-year-olds to kindergarten on time.

And the children whose families sought to give them more time to develop may be further behind. Students who spent an extra year in preschool or day care missed kindergarten, a year that focuses on playtime and socialization but has increased in academic rigor.

The number of students who started kindergarten late during the 2024-2025 school year was not immediately available Thursday, but district officials said they are aware of about 10 families who are trying to do so this fall.

—-

I think the answer to her question why is: It’s part of the struggle against (what is perceived as) white privilege: “It is difficult to determine exactly how common it is to delay a child’s enrollment in school. Some national data suggest it’s rare — somewhere between 3.5 percent and 5.5 percent of eligible children do it. Most of those students are boys born in the summer months. Academic redshirting is also more common among White children at schools that serve large numbers of wealthy families, who can afford an extra year of preschool or day care, according to an article published by the American Educational Research Association.” –Ann Althouse.

Rebecca Treiman, Jacqueline Hulslander, Erik G. Willcutt, Bruce F. Pennington & Richard K. Olson:

The goal of the present study was to test theories about the extent to which individual differences in word reading align with those in spelling and the extent to which other cognitive and linguistic skills play different roles in word reading and spelling. Using data from 1,116 children ranging from 8 to 17 years, we modeled word reading and spelling as latent traits with two measures of each skill to reduce measurement error. The models also included five skills that have been theorized to relate differentially to reading and spelling: phonemic awareness, working memory, rapid automatized naming, arithmetic, and vocabulary. The latent-trait correlation for reading and spelling was very high, 0.96, although significantly less than perfect. Vocabulary correlated more strongly with reading (0.64) than spelling (0.56), but the correlations of the other skills with reading and spelling did not differ significantly. Breaking down the sample by age, we found a significantly higher latent-trait correlation between reading and spelling in the younger half (r= .98) than in the older half (r= .94). This difference may reflect the fact that the words on reading and spelling tests are more different from one another at older ages. Our results suggest that word reading and spelling are one and the same, almost, but that spoken vocabulary knowledge is more closely related to reading than to spelling.

——-

more.

ChatGPT and its like have swept through academia, changing how students work, write and think. The bots are here to stay, so we need to reimagine learning

——-

more.

——-

To make it pedagogical, LLM is an autocomplete function that randomizes based on the statistical frequency:

I have been reading with interest the articles on our education system in Manitoba, starting with Grant Park removes advanced-placement-test due to student stress (April 29); Getting beyond just grading and tests (Think Tank, May 6); Grading by percentage is failing our students (Think Tank, May 7); and The importance of quality of assessment for students (Think Tank, May 12).

They all made me think, which is the sign of a good article. I learned that from my educators: to think for myself.

One of the articles stressed that percentages should be removed from schools due to student stress.

They advocate that no tests, no grades, and just anecdotal comments will better serve students’ needs. If this is what is happening in public schools today, I despair.

This rhetoric does not teach young people anything about striving for goals, or about having faith in their own ability to learn.

This type of thinking explains so much about the students I see in my first-year university classes. Students who can’t take constructive criticism, who bristle at instruction, and who don’t bother reading the grading rubrics before completing assignments.

They hand in anything that they have written at the last minute and expect an A because they submitted the assignment.

They come to see me at the end of the term telling me that they now have all of their late assignments ready and are wondering how to submit them.

When I explain that they can’t, they become defensive and wonder why, if it was acceptable in high school, I won’t accept them now.

They consistently miss classes and instruction and then want special treatment because they are stressed.

As a former colleague of mine at the University of Winnipeg told his students, if they aren’t stressed at university, then they aren’t trying. Life is stressful and it starts at school. Students have to know how to deal with stress when they are on their own.

It’s part of life to deal with situations that do not always go as planned.

States are starting to remove more unruly students from schools, and the Trump Administration is getting out of the way.

The Texas Legislature in May passed a bill that makes it easier for teachers to remove misbehaving students from classrooms and extends the allowable time for in-school suspensions. Some 3,300 Texas district employees were targets of student assault in 2023-24, according to the Texas Tribune. Removing students for any “unruly, disruptive, or abusive” behavior, as the legislation allows, could help prevent such escalation.

Arkansas lawmakers in April passed a law that ensures students removed for violent behavior aren’t returned to the same classroom. The Legislature also stripped from state law a requirement that districts use “positive behavioral support”—which focuses on “conflict resolution” and “coping skills”—to address student misbehavior.

Washington state’s superintendent finalized rules, effective this month, that loosen restrictions on removing, suspending, or expelling students. Other stateshave taken similar action in recent years, including Louisiana and Nevada, where the state teachers union supported legislation making it easier to remove students.

But because families have very different views on what a “good” afternoon program looks like, Alpha is now launching a series of microschools. The academic portion stays the same, but the afternoon programming varies depending on the focus. There’s one centered on sports, another on esports and gaming. But the one that stood out to me — and to the parent writing the review — is the GT School, their gifted and talented microschool. His three kids are all enrolled in GT. In that track, the afternoons lean heavily into more academic and competitive pursuits like chess and debate. But what’s different is that everything is tied to real-world validation. For example, if students do a storytelling assignment, the goal isn’t just to write the story, it’s to submit it to The Moth and get it accepted. Chess isn’t just about learning strategy; it’s about earning a national rating. Debate is expected to lead to actual competition results. The point isn’t just to complete a task. The point is to complete it and get external recognition. What really stood out, though, and what the parent-reviewer said is the true engine behind Alpha, is the school’s internal virtual currency: Alpha Bucks. Students earn Alpha Bucks for completing tasks, reaching goals, and going above and beyond. They can then spend them on real things: physical products, school events, even internal auctions. It’s an economic system that shapes motivation and behavior.

Dwarkesh Patel interviews George Church:

Mirror life, if it can be weaponized, that would take it to a whole other level of concern. The concern was that if we got it to a certain point, then it would be easy to weaponize it. Again, there’s practical considerations that maybe that most people who consider weaponizing mirror life would probably be satisfied with weaponizing viruses that already exist, that are already pathogens. And they wouldn’t want to destroy themselves and their family and their legacy and everything like that. But all it takes is one, one group probably, or one person.

But your question is, is it inevitable? I don’t know. It might be. It’s quite possible it’s already here. In other words, we already have mirror life in our solar system or maybe even on our planet. It just hasn’t been weaponized.

What we were saying in the Science paper is that this seems like the sort of thing that could wipe out all competing life if were properly weaponized. But there are probably a few things like that. What we really need to do is reduce the motivation to do that, maybe increase our preparedness for a variety of existential threats. Some of which will be natural, some of which will be one disgruntled person who has essentially too much power.

Over the history of humanity, the amount of things that a single person can do has grown very significantly. It used to be, when you had your bare hands, there was kind of a limit to what one person could do. A large number of people could team up and get a mammoth or something like that. Today, one person with the right connections or right access to technology could blow up a city. That’s a huge increase in capability. I think we want to start dialing that back a little bit somehow.

A bombshell new CIA review of the Obama administration’s spy agencies’ assessment that Russia interfered in the 2016 presidential election to help Donald Trump was deliberately corrupted by then-CIA Director John Brennan, FBI Director James Comey and Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, who were “excessively involved” in its drafting, and rushed its completion in a “chaotic,” “atypical” and “markedly unconventional” process that raised questions of a “potential political motive.”

Further, Brennan’s decision to include the discredited Steele dossier, over the objections of the CIA’s most senior Russia experts, “undermined the credibility” of the assessment.

The “Tradecraft Review of the 2016 Intelligence Community Assessment [ICA] on Russian Election Interference” was conducted by career professionals at the CIA’s Directorate of Analysis and was commissioned by CIA Director John Ratcliffe in May.

A new policy at Law360, the legal news service owned by LexisNexis, requires that every story pass through an AI-powered “bias” detection tool before publication.

The Law360 Union, which represents over 200 editorial staffers across the 350-person newsroom, has denounced the mandate since it went into effect in mid-May. On June 17, unit chair Hailey Konnath sent a petition to management calling for the tool to be made “completely voluntary.”

“As journalists, we should be trusted to select our own tools of the trade to do our information-gathering, reporting and editing — not pressured to use unproven technology against our will,” reads the petition, which was signed by over 90% of the union.

But of all the obstacles to improving reading, many attribute the greatest blame to technology.

“It’s a generational shift — text is less important [to young people] than video and audio,” says Douglas McCabe, chief executive and director of publishing at Enders Analysis.

“Tech is the biggest barrier,” agrees Sandown’s Tugwell. “They’re all on all the apps that they’re not old enough to be on, they all have WhatsApp, they’re all in massive group chats. They tell us they go on [their] X-Box [instead of reading].”

I suspect Mamdani’s “thinking” was “I think it’ll be easier to get into Columbia if I lie and say I’m black.”

——-

If I’m understanding the left’s new Race Rules correctly, my children will be able to check “Native American” on their college applications.

The scaling hypothesis has been a very … wealthy one. With people like Sam Altman (OpenAI) and Dario Amodei (Anthropic) being believers, billions of dollars have gone into making large language models (“LLMs”) like ChatGPT and Claude bigger and … BIGGER.

The belief is that just by feeding an LLM with more training data, parameters, compute, and other resources (“scaling”), Artificial General Intelligence (“AGI”) will eventually emerge.

Digital learning promises precision: personalized pathways, mastery checks, and detailed feedback to help students close gaps and build lasting understanding. But what happens when students simply ignore that feedback?

A new study dives into this hidden flaw inside a real-world mastery-based learning system , MasteryX, an adaptive German grammar app for secondary students. Its design will feel familiar to anyone who’s used systems like Khan Academy, ALEKS, or Duolingo:

Students can choose to read this feedback or skip it.

The drama unfolded largely under the radar and had an intramural angle. The investigation was led by two Justice Department officials: Harmeet Dhillon, the boss of the DoJ’s civil-enforcement division, who overlapped with Mr Ryan as a student at UVA’s law school; and Gregory Brown, another alumnus who sued UVA in 2023 and 2024 on behalf of students alleging mistreatment. Mr Trump stayed away; UVA was spared the Truth Social treatment.

The DoJ’s investigators worked with a UVA board that had been inching right in recent years. Mr Youngkin, elected in 2021, appointed 13 of its 17 members. UVA is hardly known as a bastion of radicalism but it was affected by the same charged years as everyone else. In 2020, after George Floyd’s murder, Mr Ryan promised to double down on diversity. Student tour guides emphasised Jefferson the slaveholder rather than Jefferson the founding father. Conservative faculty and students felt outnumbered and unwelcome. A group of alumni, calling themselves the Jefferson Council, criticised these developments.

I read this in shock. Are we supposed to be embarrassed to be Americans instead of Colombians or Venezuelans? Was “Go west, young man” canceled while I was on a flight this week? Is a United States that codified religious freedom really not “spiritual”? And is a professor from Yale really arguing on Independence Day that America’s problem is that it’s insufficiently tuned in to the “interdependence of human existence”? The Fourth of July has its silly side and obviously is no sacred cow, but how pathological does a person have to be to chide America for its lack of collectivist spirit on a holiday celebrating individual liberty?

Not long ago, the basics of American citizenship were uncontroversial and the challenge for all of us was living up to the ideal. As Martin Luther King put it, “All we say to America is be true to what you said on paper.” Now it’s as if our historians look back and see massacres and misery, but no Edison, Elvis, Chuck Berry, or Muhammad Ali. I don’t love the parody version of patriotism touted by Trump, but it shines through in the writings of people like Professor Gandin that they’re not proud to be Americans at all. Who can sign up for that? Why are we continually asked to choose between too much pride, and none?

We should be encouraged on this of all days to remember the good things about this country that have nothing to do with politics, from baseball to airplanes to most of the Rocky movies to just-departed George Foreman, Roberta Flack, Val Kilmer, and Brian Wilson. That’s who we are, not this dumb argument. To hell with the sourpusses. Happy Birthday, America.

England’s teenagers are in limbo. They have sat their gcse exams, which most take at 16, and will receive the results on August 21st. If they are nervous, they should be. Good gcse grades open doors to colleges and universities, whereas bad grades shut them. But teenagers in big cities should worry less. They are likely to do better than their peers elsewhere, and better than their predecessors.

“We were known for having pretty terrible schools,” says Bev Craig, the leader of Manchester City Council. In 2005 just 27% of gcse takers in the city’s state schools got five grades C or above in English, maths and three other subjects. In England as a whole, 43% did. Pupils who were entitled to free meals because of their parents’ poverty fared worse. Only 15% of Mancunians from that deprived group cleared the bar, compared with 18% across England.

The joint Madison and Dane County public health department is entering the world of online dating.

Not because it’s looking to meet other cute, single government agencies, but to better protect people from the scourge of sexually transmitted infections.

Public Health Madison and Dane County will send messages through the apps to the partners of people who test positive for STIs at agency clinics — with the goal of getting them on the phone to convince them to get tested themselves.

“As the dating landscape has changed, more people are meeting partners online,” Public Health spokesperson Morgan Finke said. “It’s just increasing our likelihood of reaching those partners by meeting them where they are.”

The messages will not contain information about the people who may have exposed them to an STI, and people will only be contacted through apps if the agency is able to confirm a profile matches a person who might have been exposed.

Wisconsin Supreme Court strikes down 1849 abortion ban. Honoring campaign promises, 4-3 liberal majority proclaims the law was “impliedly repealed.” Decision leaves in place major restrictions. 🧵 1/

More. Choose life.

The judiciary committee in the House of Representatives issued subpoenas on Tuesday to the heads of Brown University and the University of Pennsylvania, demanding they surrender documents by July 22.

The committee opened a probe into collusion earlier this year and requested documents in April, but described the universities’ responses to be “inadequate”.

The lawmakers also issued a subpoena to Harvard last month and have sought information from Columbia, Dartmouth, Cornell, Princeton and Yale, all Ivy League institution

By Matthew Fischetti and Carl Campanile

The Big Apple’s powerful teachers union is expected to announce its endorsement of Democratic mayoral nominee Zohran Mamdani — after its members passed on making a pick in the primary, The Post has learned.

Two sources close to the United Federation of Teachers said that the endorsement is coming soon from the nearly 200,000-member union after the results of the Democratic Party primary were made official this week.

The union had previously declined to endorse because members were split between Democratic socialist Mamdani, a 33-year-old state Assembly member, and former Gov. Andrew Cuomo, 67.

Like any budget that is a result of compromise in divided government, there are positive and negative aspects. But one definite positive to come from this year’s budget agreement is the continued closing of the spending gap between private, charter, and traditional public schools.

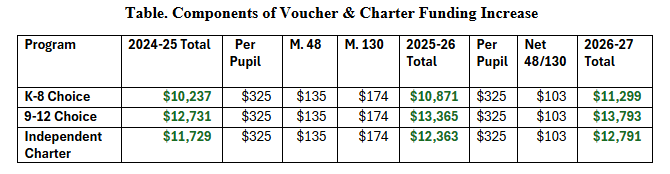

Without getting too deep into the weeds, a number of factors came together to increase funding. First, there is a categorical aid in Wisconsin known as “Per Pupil Aid.” Governor Evers’ 400-year veto—which WILL fought against—was deemed to be legal by the state Supreme Court. This funding is also provided to private choice and independent charter schools in the state, leading to an annual $325 increase in funding. While this does represent new funding each year, it merely maintains parity with the increases public schools also receive. But also included in the budget were increases that were included in several motions approved by the Joint Committee on Finance. The committee approved Motion 48 and Motion 130, which added $135 and $174 respectively per pupil choice and charter funding in 2025, and both contributed$103 in net new funding in 2026. All of these factors are listed in the table below.

For the upcoming 2025-26 school year, K-8 voucher schools will have about $10,871 per student while high schools will have $13,365. Independent charter schools will have $12,363. Note that there are other forms of charter schools in Wisconsin that contract with school districts directly and are not directly impacted by these budget provisions. Their funding amounts are set in their contract, though they have often been tied to the independent charter school level historically.

——-

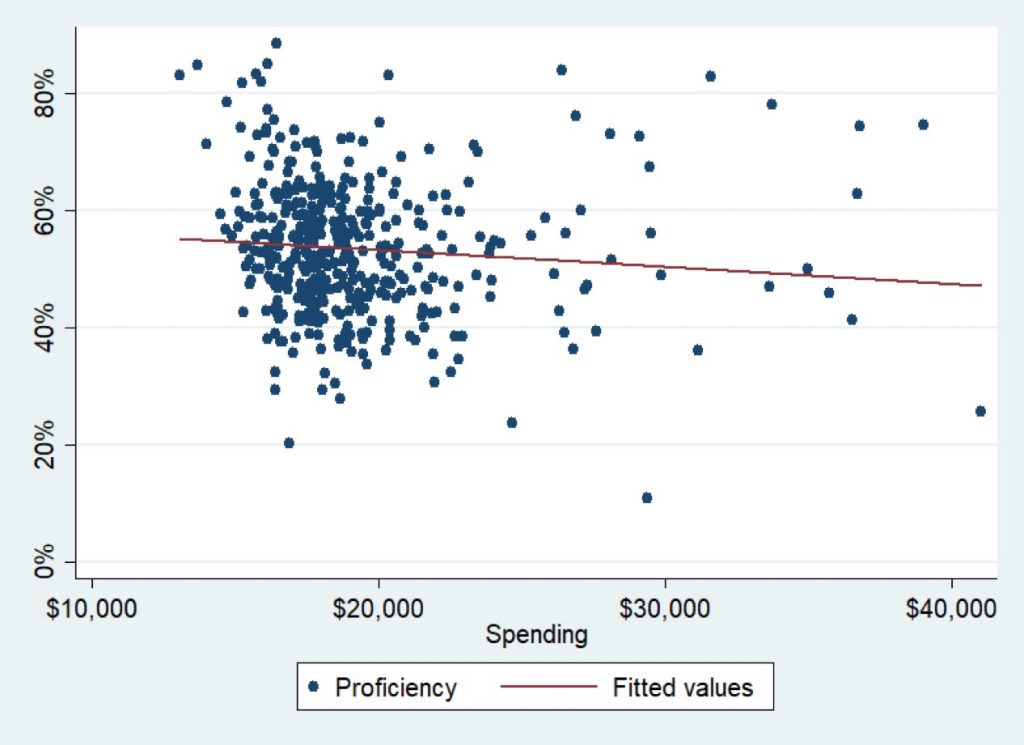

Madison taxpayers have long spent far more than most k-12 systems (currently +25k per student), this despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Darrin DeChane, Takako Nomi and Michael Podgursky

Standardized tests form the bedrock of school accountability systems and are a primary source of information for the public and policymakers alike. Over the past two decades, these tests also have come to define whether students are on track to being “college and career ready” at the end of high school, in line with state standards for what students should know and be able to do by the spring of each school year.

But many parents and educators have grown skeptical of standardized testing and the relevance of a student’s scores to their long-term success—especially tests given when children are still in elementary or middle school. Some question the typical practice of classifying students into different proficiency levels based on the scores they earned—such as below basic, basic, proficient, and advanced—to help parents and the public understand the results. What can a 14-year-old’s test scores and proficiency levels tell us about college readiness? We decided to find out and designed a study to assess the degree to which middle-school test performance and proficiency level predicts postsecondary success.

Middle-school test scores tell us quite a lot. Students with high scores on reading, math, and science tests in 8th grade are dramatically more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree within five years of finishing high school. We analyzed nine years of data for 260,000 students in Missouri, starting with their 8th-grade scores and following them through high school and the next five years to see which students graduated high school, attended college, and earned a degree. We looked at each subject test separately and in combination, and we looked at students as a whole and grouped by race and gender. Every analysis found the same trend: The higher a student’s middle-school test scores, the more likely they are to graduate high school, attend college, and earn a college degree.

Wisconsin’s public schools have fewer students in the classrooms, leaving districts across the state considering closing and combining schools.

That includes the School District of Waukesha, where officials say enrollment has declined steadily since reaching about 13,000 students a decade ago.

Last school year, enrollment dropped to about 10,500 students. District officials predict enrollment will continue to decline based on birth trends.

Democrats were unified against it, as much for partisan reasons as ideological ones. But there was also significant backlash from Republican state officials against this legislation, because many states have laws that regulate automated or AI systems. Last month, 40 GOP and Democratic attorneys general sent a letter opposing the provision, so you would think it would die. However Congress is a world apart from local concerns, and the amount of money put forward to Republican members of Congress for supporting something like this makes it hard to resist.

Still, opponents rallied. Tennessee Senator Marsha Blackburn, who is an iconoclast, “raised concerns the measure would block her home state’s Elvis Act, a law that prohibits the non-consensual use of AI to mimic musicians’ voices.” She was also concerned that the bill would disallow laws meant to protect kids. A number of other GOP Senators, like big tech foe Josh Hawley, were also worried. So Ted Cruz cut a deal with Blackburn, coming together with a “compromise” that would cut the moratorium to five years and include some ability to regulate. It’s likely this compromise was authored by Meta or one of the other big tech firms, because in some ways, it loosened protections for children. That overreach burned the compromise.

After Blackburn cut her compromise deal, there was an outcry by a host of child safety and online advocacy groups, which led to Bannon speaking with Blackburn. And she ended up opposing the full provision, either because of Senate procedure, or because the compromise was actually worse than promised. And when she flipped, Cruz realized he would lose, so he sided with her, and the provision went down 99-1.

Stacy Davis Gates warns of the Confederacy’s return to rally her base — but her actions have created a school system the Old South might well admire

Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) President Stacy Davis Gates is once again echoing Mayor Brandon Johnson’s Civil War rhetoric. “Trump has picked his side,” she claimed in last week’s address at the City Club of Chicago. “He is here to win the relitigation of the Civil War and finish the work of the Confederacy.” If Gates is searching for a school system that would be embraced by the old Confederacy, she need look no further than the CTU-dominated Chicago Public Schools (CPS).

CPS is a system that denies poor families educational alternatives to their often failing and nearly empty CTU-controlled neighborhood schools. This outcome is the direct result of the CTU’s relentless drive to secure its monopoly over public education — prioritizing the expansion of its membership and benefits, reducing workloads, and protecting jobs — while eliminating any real accountability for performance or even the behavior of its members.

The CTU and its former-employee-turned-mayor would have us believe that funding is the issue. Yet Chicago is the second-best-funded large urban school system, spending $30,000 per pupil, consuming 56 percent of all property taxes collected in the city, and receiving nearly $1 billion in additional city subsidies. Why, then, are only 11 percent of Black students proficient in reading and eight percent in math, while Latino students are only 18 percent proficient in reading and 15 percent in math?

Which raises a question: If this is what college graduates do, why exactly are we in a hurry to send so many people to college?

Over the years, we’ve seen a lot of justifications for sending people to college — by which I actually mean, for subsidizing people’s attendance at college, and for maintaining a taxpayer-funded higher education apparatus. Probably the most important are:

Okay, so how are we doing in serving those purposes? Not so great. I’ve written about this before, but here’s a sum-up.

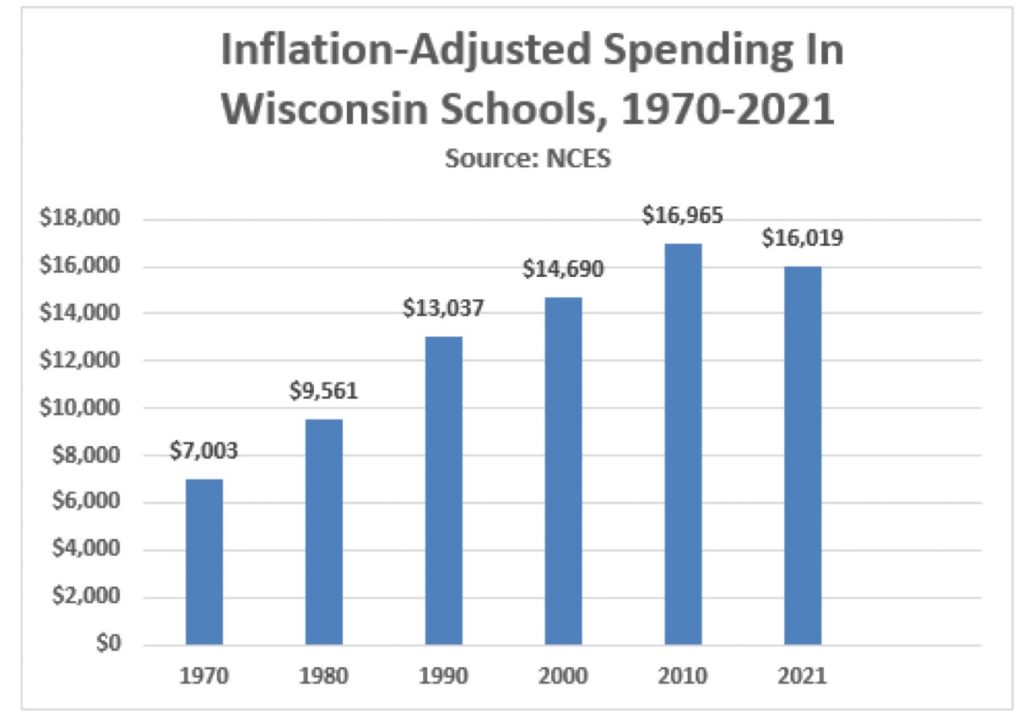

Notice the year of comparison is always 2010 for the left. Likely bc ’10 was the height of public school largesse–pre Act-10 & federal money was pouring in. A longer view shows that we’re spending $10K more per kid than 1970 to produce kids who can’t read.

School report cards have become such a farce, glorified propaganda

94% of Wisconsin schools “meet” or “exceed expectations.”

Meanwhile, only 37% of Wisconsin students can read at grade level.

But if the official report card says all is well, who is to question it?

———

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

The recently released New York math briefs (found here) are not scientific and describe questionable practices. Many of these practices have been shown through decades of rigorous research to be ineffective, especially for students struggling with mathematics. These briefs should be withdrawn.

This letter (read below) outlines serious concerns regarding grave omissions and inaccuracies in the New York math briefs in summarizing what’s purported to be evidence-based math instruction. Given the detrimental impact on New York’s youth, we are calling for a retraction of the New York math briefs. We request that they be replaced with materials that are accurate and based on evidence from rigorous empirical studies. Given recent national attention to student literacy, we are concerned that the briefs inexplicably reinforce several of the exact myths dispelled in the Science of Reading. The result will predictably be that New York’s poor math performance will not improve.

——-

2014: 21% of University of Wisconsin System Freshman Require Remedial Math

How One Woman Rewrote Math in Corvallis

Singapore Math

Discovery Math

Under the state’s complicated formula for doling out state dollars to local districts, districts that have lower than average property values per-pupil and spend less per-pupil than other districts tend to receive more state aid as their expenses go up, according to Dan Rossmiller, executive director of the Wisconsin Association of School Boards.

“In general, aid is inversely related to district property value per pupil,” he said. “To the extent that Dane County districts may have higher than average per pupil property values and tend to spend at levels above the state average, they are likely to lose aid as their spending increases over prior year levels.”

School districts typically pass preliminary budgets in the summer and then finalize them in the fall when state aid is finalized and they better know their total enrollments.

———

Madison taxpayers have long spent far more than most k-12 systems (currently +25k per student), this despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Restaurants will have to tell the government what their customers order under plans drawn up by Labour to tackle Britain’s obesity epidemic

The Department of Health intends to use the data to force big restaurant chains and fast food giants to cut customers’ calorie intake to help improve the nation’s health.

Under the proposals outlined by Wes Streeting, the health secretary, restaurants employing more than 250 workers are expected to report the average number of calories that diners consume.

The government will then set targets to “increase the healthiness of sales”. The department said the policy would “set full transparency and accountability around the food that businesses are selling and encourage healthier products”.

Theoretically and now legally, parent opt outs could fill school cafeterias for all kinds of reasons. “The fight is far from over,” predicts a lawyer at WI Institute for Law & Liberty.

Mahmoud v. Taylor 2025 arose from mandatory classroom indoctrination beginning in kindergarten with story time about two male knights who marry each other. Another features a biological girl who transitions to a boy. (There’s equity for ya!)

Teachers in a Maryland district in the D.C. metro area were told to teach, “When we’re born, people make a guess about our gender and label us ‘boy’ or ‘girl’ based on our body parts. Sometimes they’re right and sometimes they’re wrong.” But “the community” is never wrong. Right?

Remember when schools taught reading and writing? No one knows the difference any more between “your” and “you’re,” much less what is woman! (Don’t ask Tim Walz!)

We read that liberal Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson argued that instead of the constant opt outs, parents should remove their children from public schools. Good idea! The Werkes wishes progressives would embrace school choice.

Ted Dabrowski and John Klingner

The district’s two high schools have the worst results of all. At East St. Louis Senior HS, just 5% of students score proficient in reading on the SAT and just 2% score proficient in math.

The SIU charter school is even worse with 7% reading and 0% math.

To add insult to injury, East St. Louis graduates 74% of its students each year

“To end overreach from Washington and restore the rightful role of State oversight in education, the Budget proposes to eliminate the misnamed English Language Acquisition program which actually de-emphasizes English primacy by funding [nongovernmental organizations] and States to encourage bilingualism,” the administration stated. “The historically low reading scores for all students mean States and communities need to unite — not divide — classrooms using evidence-based literacy instruction materials to improve outcomes for all students.”

Advocates for English learners support “evidence-based literacy instruction,” but take issue with much of the rest of the administration’s assertions, including the claim that programs to help students learning English are divisive.

“We want our students to gain proficiency in English so that they can access their education in English,” said Martha Hernandez, executive director of Californians Together, a coalition of groups that advocates for English learners. “And the majority of English learners are in English-only settings. These funds help students learn English.”

On a blustery spring Thursday, just after midterms, I went out for noodles with Alex and Eugene, two undergraduates at New York University, to talk about how they use artificial intelligence in their schoolwork. When I first met Alex, last year, he was interested in a career in the arts, and he devoted a lot of his free time to photo shoots with his friends. But he had recently decided on a more practical path: he wanted to become a C.P.A. His Thursdays were busy, and he had forty-five minutes until a study session for an accounting class. He stowed his skateboard under a bench in the restaurant and shook his laptop out of his bag, connecting to the internet before we sat down.

Harvard University is asking major corporations for research funding after President Donald Trump revoked more than $2 billion in federal grants from the school over campus anti-Semitism and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives.

Harvard is “ramping up conversations with big technology and pharmaceutical companies in efforts to drive more corporate funding so research stays active,” the Wall Street Journal reported Friday. The talks remain in early stages, with no new funding agreements yet secured, according to university and company sources.

The corporate outreach comes as Trump has cracked down on Harvard for failing to protect Jewish students from violent protesters and implementing what he calls “discriminatory and illegal” DEI policies. Trump has frozen nearly $3 billion in federal funding from Harvard, revoked the school’s authorization to host international students, and proposed removing Harvard’s tax-exempt status if the university “keeps pushing political, ideological, and terrorist inspired/supporting ‘Sickness.'”

In this oped in the @gbpressgazette, a number of school district leaders either have lied about school choice funding or don’t even understand the basics of how funding works in Wisconsin (1/5)

According to the governor’s office, new spending under the state budget deal will include:

Earmark Transparency Report.

——-

Meanwhile, federal taxpayer news:

New voucher provisions in the OBBB vote tonight include:

Feds and states can regulate private schools who participate and the SGOs that manage them.

Unlimited amount of funding for this- no $4b cap on total contributions. Could cost much more (see IRA tax credits)

More.

——-

From the 2024 Financial Report of the United States[1] comes the understatement of the century:

The total resources needed for all the programs sums to $175.3 trillion in PV terms. This need can be satisfied only through increased borrowing, higher taxes, reduced program spending, or some combination.

Translation: the average American’s assets are the government’s collateral[2,3]. Because US citizens have freedom of speech, and the right to bear arms, but no amendment that establishes a max tax. As such, their assets will be seized to pay for their profligate state.

Below is the relationship between the newest spending data in Wisconsin and student proficiency in reading. It should put to bed–once again–that more money equals better outcomes. The line here is negative–higher spending districts do worse on average.

As part of a pilot program called Wisconsin Rural Scholars, high school students from seven small and rural high schools around the state spent a week at UW-Madison in mid-June aimed at introducing them to the college environment. The program is funded by a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant and was free for students to attend.

To understand context engineering, we must first expand our definition of “context.” It isn’t just the single prompt you send to an LLM. Think of it as everything the model sees before it generates a response.

The law calls for a multi-faceted overhaul of the state’s elementary school reading curriculum. It aims to improve reading proficiency by emphasizing phonics and prohibits some methodologies, such as one in which young readers use clues to learn unfamiliar words. Critics say that leads to more guessing and lower rates of reading proficiency.

The law, known as 2023 Act 20, requires districts to use phonics-based curriculum — a potentially pricey change, based on when districts last updated their materials. Elementary school teachers also are required to go through updated professional development and training, which can cost hundreds of dollars per teacher.

The law also requires school districts to develop ways to screen how well students read and get them back on track, as well as reporting that information back to the lawmakers. Students who score below the 25th percentile would get personalized reading plans, which often requires the hiring of reading specialists.

Lawmakers set aside $50 million to help school districts cover the cost of assessments and reimburse them for up to half of the cost of new curriculum, for which there are four options approved for purchase. But new curriculum can cost a million dollars or more per school district, depending on the number of students, said Dan Rossmiller, executive director of the Wisconsin Association of School Boards, and there are 420 public school districts in the state.

“It’s a good thing that our state recognized that reading instruction was not where it needed to be, but it’s really unfortunate commentary that we didn’t put our money where our mouth is, or if we did put some money where our mouth is, we didn’t put enough,” Rossmiller said.

School districts could be sued if they don’t comply with the law.

——-

Legislation and Reading: The Wisconsin Experience 2004-

——-

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

The party that invented public charter schools under Bill Clinton, then scaled them under Barack Obama, can’t even say “charter school” in mixed company under Randi Weingarten, without whispering and peeking to check who might be listening.

Kamala Harris talked about choice and freedom in every campaign speech, but never about schools. That wasn’t an oversight — it was by design.

While the consequences of Weingarten’s leadership have been tragic for American children, the implications are also devastating for a Democratic Party struggling to regain credibility with working class voters.

In a packet prepared for the law school’s affinity groups, the journal instructed minority students to highlight their race and gender as part of their personal statements—and revealed that they would earn extra points for doing so.

The packet, obtained exclusively by the Washington Free Beacon, included the rubric used to evaluate the personal statements. Applicants can earn up to 10 points for explaining how their “membership in an underrepresented group” will “lend itself to … promoting diverse voices,” and an additional 3-5 points if they “hold a leadership position in an affinity group.”

To drive home the point, the packet included four examples of personal statements that had gotten students on the law review. Three of those statements referenced race in the first sentence, with one student boasting that, “[a]s an Asian-American woman and a daughter of immigrants, I am afforded with different perspectives, experiences, and privileges.”

A fourth student waited until the last paragraph to disclose that she was “a Middle Eastern Jewish woman,” an “intersectional identity” she said would “prove useful” in a “collaborative environment.”

“You can really assert your dominance by swearing, especially when you’ve got the licence to swear but other people don’t have,” Michael Adams, professor of English language and literature at Indiana University and author of In Praise of Profanity, tells me. “It’s like [Trump’s] use of nicknames — he can only be addressed as Mr President, so it sets up this kind of imbalance of power.”

Other world leaders could in theory, of course, follow Trump by indulging in a good bit of expletive uttering of their own. But it is not easy to think of many who would dare. And even if they did, it might not land: part of the reason Trump can get away with it is that it doesn’t feel like a deviation from his behind-the-scenes vernacular. He doesn’t look awkward when he swears. Much as he might try to put on presidential and “elegant” airs, and despite being born into privilege, Trump is at his core a brash, wheeler-dealer, anything-goes New Yorker.

——-

37 But let [a]your ‘Yes’ be ‘Yes,’ and your ‘No,’ ‘No.’ For whatever is more than these is from the evil one.

They want to be promoted after only a few months, treat the office like their bedroom, show up in sweats or skimpy office-siren fits, FaceTime friends from their desks, and ghost their managers.

This is the gist of employer complaints about Gen Z workers, who seem to be having a uniquely hard time getting along in the office — much worse, managers say, than the generations before them. In a December 2024 survey of 1,000 employers by Intelligent.com, 12.5% said a Gen Z candidate had brought Mom or Dad to a job interview. The bosses are fed up.

Gen Zers, meanwhile, see things differently: From their perspective, millennial and Gen X managers have no work-life balance. “No cap. My manager Slacks me at 10 p.m.,” said Kevin, a 23-year-old engineer who lives in SoMa. “That’s not OK.” It appears to be a common theme. “Still waiting for that work-life balance they promised us,” one young person tweeted in response to a complaint about Gen Z employees.

Notable omissions from the top 10 included Yale and Princeton, though they figured in the top 30, while no European university breached the top 20.

The Mojo Mortgage report also looked into what unicorn founders were studying at university. The results were unsurprising, with business and STEM degrees dominating.

93 unicorn founders had an MBA, accounting for nearly 20% of the prestigious group of entrepreneurs. Computer science was the most popular subject overall, with 75 holding bachelors, 40 holding masters, and 12 holding a PhD. With the vast majority of unicorns being digital tech-related, the computer science concentration is a given.

——

Every single one of the 11 Meta superintelligence hires is an immigrant who did their undergrad abroad.

If you had told me at my Year 13 graduation, that I would be standing here today, I would have been extremely amused.

Let me start off by telling you a story.18 years ago, at my own LHS graduation, the historian Robin Lane Fox was the guest speaker. If you don’t know Robin Lane Fox, his works on Early Christianity and Alexander the Great are fantastic.

Back in 2007, I was no esteemed guest, but rather, like most teenage girls, a jumble of competing interests and personalities. I had high hopes of becoming an archaeologist or historian myself, but due to my disobedient nature, including trying to sell this school in a local newspaper, I admit I barely made it through LHS.

But after luckily pulling it together for my A-Levels, when I got up on stage at graduation to shake Robin’s hand, I found that- with no notice or warning given to the audience and after shaking the hands of dozens of girls- Mr. Lane Fox kissed me on the cheek.

All eyes were on me as I walked back to my seat, as it was presumed, considering my naughtiness, that I had somehow done something to initiate the incident, or as my mother later put it it very much looked from the back of the hall that you had kissed him’

It was only towards the end of the ceremony that Lane-Fox mentioned that he had kissed the cheek of any girl who had graduated with A-Levels in the classics trifecta, Latin, Ancient Greek and ClassCiv, which had been my subjects.

When I was contacted to see if I would be the guest speaker here today, my decision rested on one condition. Was LHS still teaching classics and the arts with the same intensity? I looked at the curriculum online and saw that yes class’ civ and latin were still mandatory, with a few exceptions.

Having access to all STEM subjects and the full range of humanities, while also being a Steinway-accredited school of music, is such a gift.

To all the teachers and staff here, and to all those who have kept this school going for the last 175 years, I want to say thank you.

Thank you for keeping education glorious. There are many schools worldwide that have sacrificed the classics for the temporal educational trends of modernity, and you have remained resilient in providing thousands of girls with access to a timeless and historical education.

For every one of me here, there are hundreds of other girls whose lives you’ve enriched and who are endlessly grateful.

I could not appreciate the value of this education in my youth, just as you girls here can not fully grasp its significance today. Yet in later years, you may find that your encounters with literature or distant places carry a deeper resonance-words and concepts that once felt like burdens imposed by this very institution will reveal layers of meaning that others overlook.

The Latin inscriptions adorning a Roman church fresco’s ceiling, or the subtle tributes in novels to classical thinkers you once studied, will quietly illuminate a secret world.

The rewards of the education you have been given will not emerge in classrooms or exams, but in the unscripted encounters of a life well-lived.

I won’t kiss anyone today; instead, I will share the most important message I think I can give.

Make the most of this great education that you have been given.I am just one voice of a thousand annoying experts and adults who will tell you how you should live your life. There will be plenty of warnings about what’s bad for you and how to protect your physical and mental health as you graduate into a complex and busy world.

Most people won’t risk telling you what’s good for you, but I’m up here perhaps only because l’ve taken more risks than my peers. I have been successful, and I also spent years living in a tiny office closet. I have been popular and I have felt hated. I have made millions, and I have lost millions. I’m proud of some of my work, yet I’ve spent many nights lying awake, cringing at ideas I once defended fiercely. Mistakes and failures litter my path, and each one taught a lesson that helped fine-tune my future actions.

And like all women, I have felt beautiful, and I have felt ugly.It doesnt matter.

Nothing has mattered more in my life than cultivating beauty and philosophy. Spending time and energy seeking it out—in old buildings, paintings, poems, and old books, in the autobiographies of great humans, to find inspiration on how to live a good life.

Modernity moves quickly; what is timeless, by definition, has stood the test of time.

Traditional experts don’t want you to know that you can inject beauty into any moment as a conscious decision. Beauty isn’t defined by aesthetics; it’s about intention.Make moments intentional. Make career decisions intentionally. Be very intentional with your time, yet when something feels off appreciate that you have all the agency to completely change it.

Take risks fully, intentionally. Spend time with people fully, intentionally, always with the notion that one day that person you’re spending time with may no longer be here. If you can, get to know your parents as if they are your friends, in them you may learn about yourself.

Travel and see the world, intentionally or recklessly. There are so many flavors of life, so many cultures, so many different types of living and people. For some of you, this part of England may be the best place for you to flourish, but make the decision to spend your life here consciously, with full awareness of how big the world is.

I am living testament that you don’t need family money to be able to travel or seek opportunities. During my gap year, [I] sold plastic garden sinks at trade shows to save up and travel to new lands.

In the end, I found my people and the culture where I belong on the other side of the world, in San Francisco, California. moved there originally at 24 years old with the ambition to launch an artificial intelligence start-up fund, which I did, kinda, though it was no big success.

I had no idea what I was doing.

But in the countless cold emails I sent and the essays I published I found not only friends, but people with similar visions who recognized mine, and over the last decade we have built projects and companies together.

San Francisco is a paradise of socially awkward tech lovers who throw awful parties while debating philosophy endlessly.If that sounds like a place you’d fit in, reach out to me and I’ll show you around.

But your people might be scattered across places like London or Singapore, or they’re waiting for cities that don’t exist yet that need you to instigate and design them, or maybe they’re launching rockets toward Mars with dreams of new worlds.

You can’t know yet.

The world is an uncharted adventure waiting for you to explore.

Make the most of this freedom while also remembering that it is every generation’s responsibility to defend the same freedom for future generations. Over time, you might learn that such freedom is found in the opposite of whatever the media and news sell you.

Experts are nearly always wrong because expertise is a transient quality. Artificial intelligence is mostly wrong, too, because it is trained on the corpus of eternally fallible humans.

But if you shrug off the noise the world shoves at you, beauty and joy will slip in effortlessly. Elegance can be found in a semiconductor’s complexity, a violin concerto, a flower’s bloom, even a line of code. I’m not ashamed to admit that all of these things can move me to tears, and do often, daily.

If you really notice and take in the world, it’s overwhelming.

If you really notice and take in the world, it’s difficult to be depressed.

Back in 2007, I didn’t know what the future held for me, but I knew I wanted to try as many flavors of life as possible. And in 2025, I feel the same.

I could easily repeat the last ten years for the rest of my life, navigating technology companies and repeat opportunities that eventually become easy.

Or I could become a painter, or poet, a surgeon, a truck driver.

With the internet in your pocket, anyone can teach themselves a whole new field or career path at any time. Sometimes I spend weeks or months studying a niche area of research just for fun. I can tell you a lot about neurodegenerative diseases but I never learned to drive a car. Your choices don’t need to make sense to other people.

You are never too young or too old to start again, to move away, to restart your life, and to completely redesign your mind.

It’s the most freeing thought.

All your limitations, now and in the future, are self-imposed.

Thank you and .. good luck.

Notes and links on Riva Tez.

I realize I’m a lawyer and Peter is not, but each state is divided into a total of 94 district courts (some just one district). Those districts are all underneath one of 12 courts of appeal. Under the laws of the US, a district in TX cannot bind a district in CA and the 1st circuit cannot bind the 12th. Cases work up the Supreme Court through appeals and only it can decide issues at a national level. That is very basic and I am surprised a reporter does not know that.

This summer marks a truly historic moment in our journey. On Friday, July 11, 2025 in the auditorum at Trustage, the same place where we announced the creation of One City Schools 10 years ago to an audience of 400 community leaders and supporters, we will celebrate our first class of 8th graders: 25 remarkable Scholars who are completing their middle school education at One City Preparatory Academy next month. These young leaders represent the living embodiment of our mission: to prepare students for school success, leadership, and life through innovative education that nurtures both academic excellence and character development.

When we founded One City, we envisioned a day when our Scholars would stand ready to change the world, equipped not only with a great education but also with the habits of character that define who we are: Compassion, Risk-taking, Integrity, Self-respect, and Persistence (CRISP). Today, that vision becomes reality. Our 8th graders are heading to ten different high schools across the Greater Madison community, carrying with them the confidence, curiosity, and courage to pursue their dreams while making their communities better.

This milestone belongs to all of us. To the parents who trusted us with their most precious gifts. To the donors who believed in possibility over statistics. To the volunteers, policy makers, and community champions who stood with us when this was just a bold idea. Together, we’ve proven that with the right resources and unwavering commitment, we can close achievement gaps and open doors of opportunity for every child. Thank YOU for the role you’ve played in helping us reach this remarkable and emotional milestone.

As we celebrate this achievement, we’re already building for the next generation. Join us at Rally for Our Future on July 10th at The Sylvee, featuring actor and literacy champion, LeVar Burton (known for Reading Rainbow, Star Trek, Roots, and The Right to Read), as we continue our mission to show what’s possible when a community comes together for its children. Visit www.weareonecity.org to learn more about this community engagement and fundraising event, and purchase your tickets. You can also click on the image of Mr. Burton, or on buttons, below.

Because our 8th graders are just the beginning, they are the first of many who will lead us toward a brighter, more equitable future for all. Our current 7th grade class is twice as large and will be equally prepared to succeed in high school.

With gratitude, hope, and inspiration, Onward!

Kaleem Caire

Founder and CEO

One City Schools

Penn State currently holds a $4.78 billion endowment, a figure that has more than doubled since 2016. Pitt’s $5.8 billion endowment has grown by 66% in the same span. Temple reported a 10.35% endowment increase in 2024 alone, bringing it to more than $960 million. As of 2023, Lincoln’s endowment was reported at $54 million.

By contrast, West Chester University in the southeastern region of the state is considered among the top PASSHE schools and has a reputation for its strong financial management. Its endowment was reported at $61.1 million in 2023. Slippery Rock University, another PASSHE top performer, is situated just north of Pittsburgh. Slippery Rock reported its endowment at $47.9 million the same year. On the other side of the PASSHE financial spectrum, the much smaller Cheyney University came in at just $1.7 million.

Cheyney and Lincoln represent the state’s only two historically Black colleges and universities. Despite their historic stature, both having been established before the Civil War took place, they demonstrate the wide expanse of financial pictures in both state systems.

The disparities make it difficult to get a comprehensive view of Pennsylvania’s higher education landscape. Nevertheless, they come to the state’s appropriation committees in two groups, PASSHE and state-related, for the annual tug-of-war over additional funding.

…….

Shieh said the university employs 3,805 full time non-instructional staff for 7,229 undergraduate students.

“This isn’t education; this is bloat paid for on the backs of families who are mortgaging their futures for a shot at a better life,” Shieh said.

Shieh said budget cuts at Brown led to dorm flooding and “unappetizing” changes to food at Brown’s dining halls while many administrators remained on payroll.

The San Francisco Unified School District’s ethnic studies class has been a source of debate among officials, donors, and parent organizers since an investigation by The Standard last month outlined the unconventional approval process behind the course and its politically charged content.

According to sources, the district decided to cancel the ethnic studies program for the next school year to assuage concerns over the course, which was mandated for all high school freshmen in 2024-25.

The course would remain a graduation requirement for incoming freshmen but would not be offered to any high school students next year, giving district staff time to develop an alternative curriculum and get it approved by the board.

But teachers are fighting back, and the district is considering rushing through an updated curriculum to keep the course in place for 2025-26, sources say.

All of this will require a higher level of cognition than does the rote work many white-collar employees now do. But as AI is getting smarter, young college grads may be getting dumber. Like early versions of ChatGPT, they can regurgitate information and ideas but struggle to come up with novel insights or analyze issues from different directions.

The brain continues to develop and mature into one’s mid-20s, but like a muscle it needs to be exercised, stimulated and challenged to grow stronger. Technology and especially AI can stunt this development by doing the mental work that builds the brain’s version of a computer cloud—a phenomenon called cognitive offloading.

Growing research shows that handwriting engages parts of your brain that play a crucial role in learning and helps children with word and letter recognition. Taking notes by hand also promotes memory development by forcing you to synthesize and prioritize information. When you plunk away on a keyboard, on the other hand, information can go, as it were, in one ear and out the other.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

U.S. job hunters submit millions of online applications every year. Often they get an automatic rejection or no response at all, never knowing if they got a fair shake from the algorithms that gatekeep today’s job market.

One worker, Derek Mobley, is trying to discover why.

Mobley, an IT professional in North Carolina, applied for more than 100 jobs during a stretch of unemployment from 2017 to 2019 and for a few years after. He was met with rejection or silence each time. Sometimes the rejection emails arrived in the middle of the night or within an hour of submitting his application.

Mobley, now 50 years old, noticed that many of the companies he applied to used an online recruiting platform created by software firm Workday WDAY 0.07%increase; green up pointing triangle. The platforms, called applicant tracking systems, help employers track and screen job candidates.

In 2023 Mobley sued Workday, one of the largest purveyors of recruiting software, for discrimination, claiming its algorithm screened him out, based on his age, race and disabilities. Mobley, a Black graduate of Morehouse College who suffers from anxiety and depression, said the math didn’t add up.

“The media is melting down, and neither billionaires nor journalists can seem to stop it,” writes The Hollywood Reporter. “Journalism may never again make money,” states the Washington Post. “Is American journalism headed toward an ‘extinction-level event’?” asks The Atlantic. Indeed, an obituary for the American press is overdue. And it turns out that the death of journalistic objectivity has been both cause and effect.

Josh Chin and Niharika Mandhana:

Authorities frustrated by continued resistance to Beijing are now prying children as young as four years old from their homes—before they have a chance to fully absorb the Tibetan language and way of life.

Across Tibet, a mountainous region rich in natural resources where many people harbor dreams of independence, China is spending hundreds of millions of dollars to build schools, recognizing how social identity forms early in life. The education project includes a network of daylong preschools, where children are taught in Mandarin, and lessons emphasize Chinese culture.

🧵The White House just dropped these mini video profiles highlighting America’s first patriotic legends, celebrating their enduring contributions that founded this nation.

This thread will contain them. Bookmark worthy.🙂

Roughly six million federal student-loan borrowers are 90 days or more past due after a pandemic-era reprieve ended, according to TransUnion. The credit-reporting company estimates that about a third of them, or nearly two million borrowers, could move into default in July and start having their pay docked by the government. That’s up from the 1.2 million that TransUnion had estimated in early May.

An additional one million borrowers are on track to default by August, followed by another two million in September. Borrowers fall into default when they are 270 days past due.

Some borrowers might be having communication issues with their student-loan servicers, while others might be too financially stretched to make payments, said Joshua Turnbull, head of consumer lending at TransUnion.

The Education Department restarted collections on defaulted student loans in May, something it hadn’t done since before the pandemic. The department sent notices to borrowers saying their tax refunds and federal benefits could be withheld starting in June if they don’t take steps to resume payments.

Wage garnishment is also set to restart this summer. Until past due payments are paid in full or the default status is resolved, borrowers could see up to 15% of their wages automatically deducted from their paychecks.

In his latest book, How Countries Go Broke, Dalio purports to lay bare the key elements of his uber-profitable investing strategy, especially how to look for the risks of once-in-a-generation shifts that most investors — and policymakers — are oblivious to until is it is too late.

Critically, he emphasises the importance of looking at very long historical data sets in order to be able to distinguish epoch waves, sometimes a century long — including what he calls the “Big Debt Cycle” — from typical cyclical business ups and downs which are smaller and less consequential.

“Big debt crises are inevitable,” Dalio writes in his opening chapter, pointing an accusatory finger at poor and imperfect lending decisions that result in too much credit. “Throughout history only a very few well-disciplined countries have avoided them.” Others have been destroyed by them.

To avoid such a fate, Dalio claims that by using metrics — which involve debt, income, interest rates, savings, growth and so on — one can go a long way to calling the timing of crises. The book is packed with charts, equations and highlighted action points illustrating just how a country might “go broke”. Data geeks will not go unrewarded. Yet it is thin on concrete case studies or statistical tests. Instead, the book largely appeals to the fact that whatever exactly the strategies are, they made the author a lot of money.

It is also curious that Dalio sees no need to reference well-known earlier books — including, full disclosure, my 2009 book with Carmen Reinhart, This Time Is Different — that predate his, employ extensive archival data research and reach broadly similar conclusions regarding the critical importance of looking at very long multi-country time series if one wants to assess the probability of rare debt, financial crisis and inflation events.

It would have been interesting to know more. Indeed, a recurrent theme of the empirical literature is that financial and debt crises are hard to predict with any kind of precision until close to the event. There are some well-known indicators. In the case of a country debt crisis, these include an overvalued exchange rate, sustained large government budget deficits and current account deficits, and high indebtedness to foreigners. Even so, such indicators, which by the way all apply to the US today, do not yield the kind of precision on timing an investor needs to really score a big killing.

Thomas Renault, Mohsen Mosleh, and David G. Rand:

We use crowd-sourced assessments from X’s Community Notes program to examine whether there are partisan differences in the sharing of misleading information. Unlike previous studies, misleadingness here is determined by agreement across a diverse community of platform users, rather than by fact-checkers. We find that 2.3 times more posts by Republicans are flagged as misleading compared to posts by Democrats. These results are not base rate artifacts, as we find no meaningful overrepresentation of Republicans among X users. Our findings provide strong evidence of a partisan asymmetry in misinformation sharing which cannot be attributed to political bias on the part of raters, and indicate that Republicans will be sanctioned more than Democrats even if platforms transition from professional fact-checking to Community Notes.

More.

The decline of the expert class can be traced to the changes in higher education over the last couple of decades. As I discuss in my book The Indispensable Right, an orthodoxy has taken hold of most universities with a purging of conservative, libertarian, and dissenting faculty. Within these ideological echo chambers, appointments, publications, and grants often seem to turn on conclusions that favor political agendas.

Over the years, dissenting faculty members have been forced out of scientific and academic organizations for challenging preferred conclusions on subjects ranging from transgender transitions to COVID-19 protections to climate change. Some were barred from speaking at universities or blacklisted for their opposing views.

As shown during COVID, many of the exiled experts were ultimately proven correct in challenging the efficacy of surgical masks or the need to shut down our schools and businesses. Scientists moved like a herd of lemmings on the origin of the virus, crushing those who suggested that the most likely explanation is a lab leak (a position that federal agencies would later embrace).

Scientists have worked with the government in suppressing dissenting views. At the end of last year, The Wall Street. Journal released a report on how the Biden administration suppressed dissenting views supporting the lab leak theory, as dissenting scientists were blacklisted and targeted.

There’s no existing model for Acton’s candidacy — she’s the only Covid-era health director using that experience as a springboard to run for a top statewide office, at a time when the only sitting U.S. governor who was previously a physician is Democrat Josh Green of Hawaii. How voters ultimately assess her will offer a window into how a segment of the country has processed the pandemic and its aftermath half a decade later.

The takeaways won’t be definitive. Acton enters the race at a distinct disadvantage, beyond even her reputation on the right as the chief architect of the state’s divisive lockdowns. Donald Trump ushered in a new conservative era in Ohio, the state responsible for making JD Vance a senator. The likely GOP nominee for governor is Vivek Ramaswamy, a MAGA celebrity from Cincinnati who has effectively cleared his own primary with endorsements from Trump and the Ohio Republican Party. Acton may not even win her own primary next May, which could feature ex-Sen. Sherrod Brown and former Rep. Tim Ryan, two of the state’s most prominent Democrats. That hasn’t stopped Ramaswamy from treating Acton as his opponent, calling her an “Anthony Fauci knockoff” who “owes an apology to every kid in Ohio for the Covid public school shutdown.”

———

More.

———

Awaiting an analysis of the long term costs of taxpayer supported Dane County Madison Public Health “mandates”.

Rachel Louise Ensign, Chao Deng, Maggie Grether and Jack Gillum:

Most electoral districts where at least a quarter of residents had bachelors degrees broke mostly for Mamdani over former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Wall Street Journal analysis of preliminary election results and census data found.