We also look at Wisconsin’s largest school choice program–open enrollment. Here, you see the marketplace working as families move to school districts with better academic outcomes and graduation rates.

WILL’s Apples to Apples report provides a rigorous, side-by-side comparison of academic performance across Wisconsin’s public, charter, and private choice schools. Because student achievement is strongly shaped by factors such as income, disability status, and English learner status, simple comparisons of raw test scores can be misleading.

This report addresses that problem by applying a consistent analytical framework that adjusts for key student and school characteristics, allowing for fairer comparisons across sectors. The 2026 edition uses the most recent data from Wisconsin DPI’s 2024–25 report cards and reflects important methodological updates, including the addition of disability rates as a control variable directly for the first time.

———

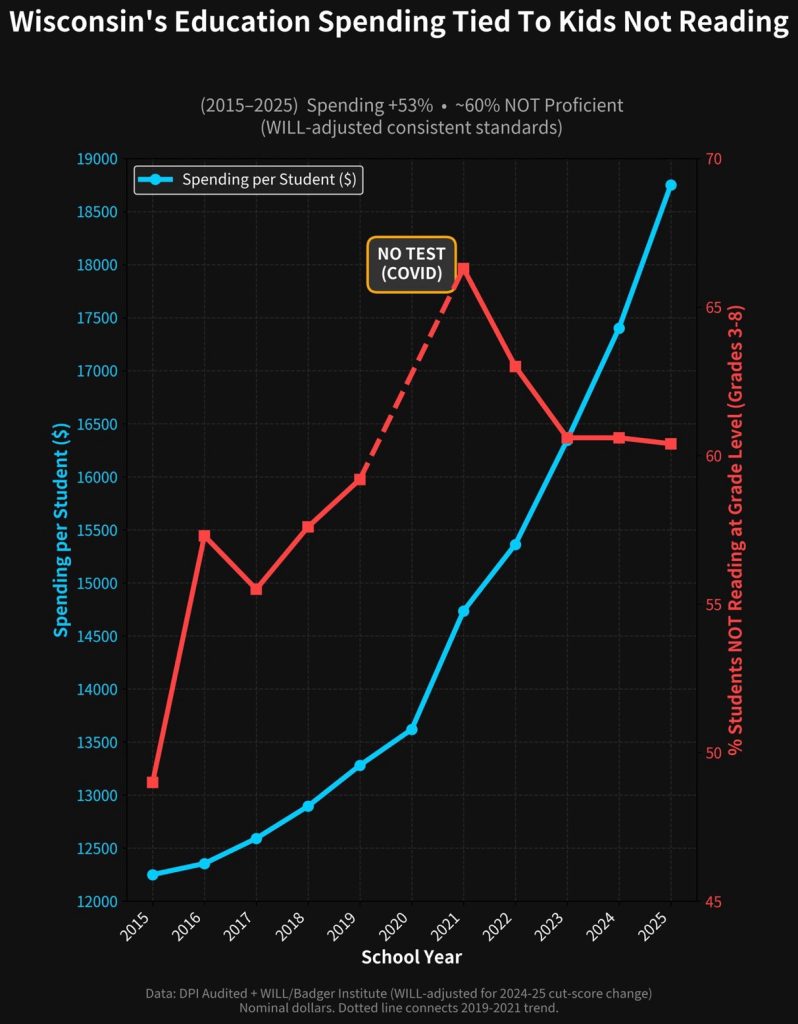

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

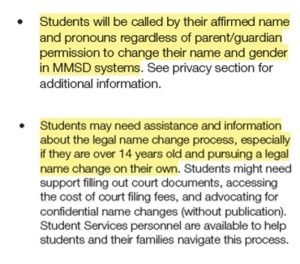

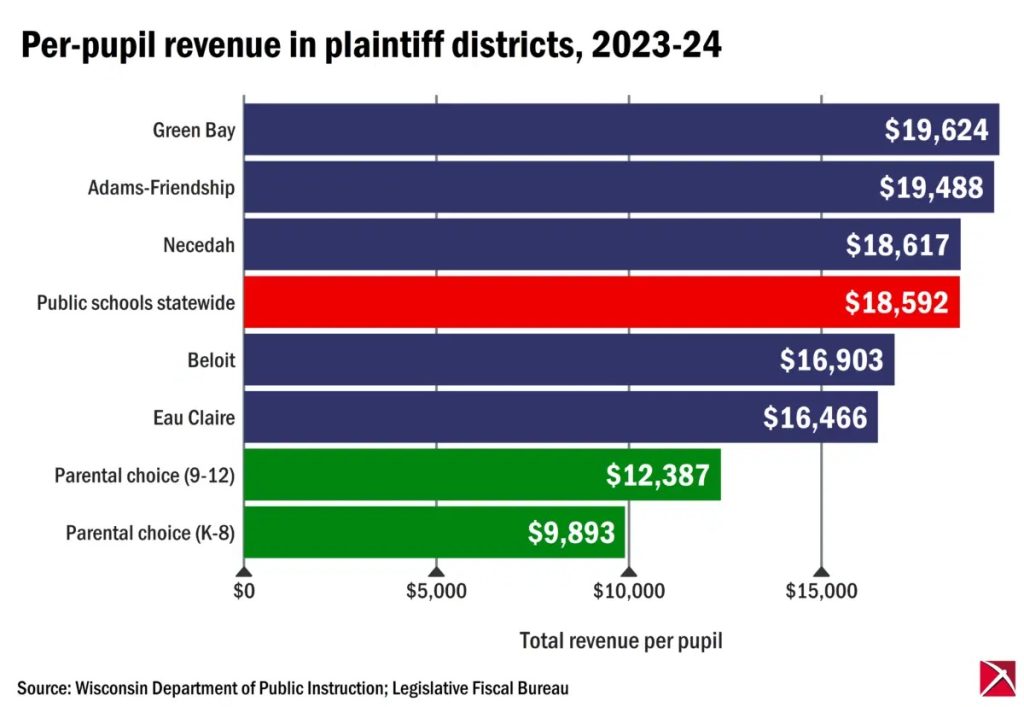

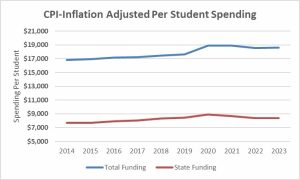

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

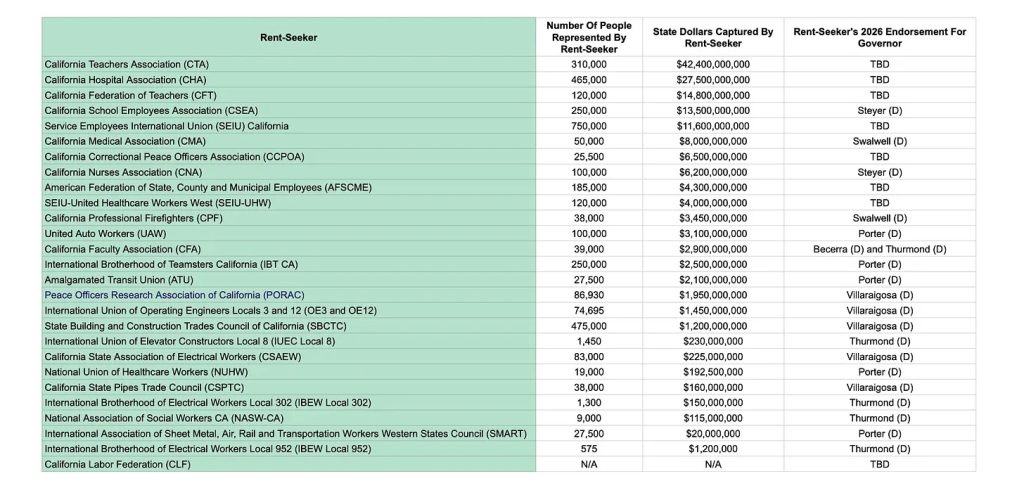

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy