Search Results for: We know best

New Evidence Raises Doubts on Obama’s Preschool for All

Last week legislation was introduced in the Senate and House to create federally funded universal pre-k for 4-year-olds. The details of the legislation are largely consistent with the White House proposal, called Preschool for All, that was announced in the president’s state of the union address in February.

The rhetoric around the introduction of the legislation includes the by now entirely predictable and thoroughly misleading appeal to the overwhelming research evidence supporting such an investment. For example, Senator Harkin, the lead author of the Senate version of the legislation, declared that “Decades of research tell us that … early learning is the best investment we can make to prepare our children for a lifetime of success.”

By way of background, I’m a developmental psychologist by training and spent the majority of my career designing and evaluating programs intended to enhance the cognitive development of young children. For instance, I directed a national Head Start Quality Research Center; created a program, Dialogic Reading (which is a widely used and effective intervention for enhancing the language development and book knowledge of young children from low-income families); and authored an assessment tool, the Get Ready to Read Screen, that has become a staple of early intervention program evaluation. My point is that I care about early childhood education and believe it is important – as witnessed by how I spent my professional life for 30 years.

My career since 2001 has largely been about advancing evidence-based education, which is the endeavor of collecting and using the best possible evidence to support policy and practice in education. Since the president’s state of the union address, I’ve been writing that the evidence is decidedly mixed on the impact of the type of preschool investments the president has called for and that we now see in the legislation introduced in Congress. It may seem in the pieces I’ve written that I’m wearing only my evidence-based education hat. But in fact if you’re an advocate of strengthening early childhood programs, as I am, you also need to pay careful attention to the evidence – all of it. Poor children deserve effective programs, not just programs that are well-intentioned.

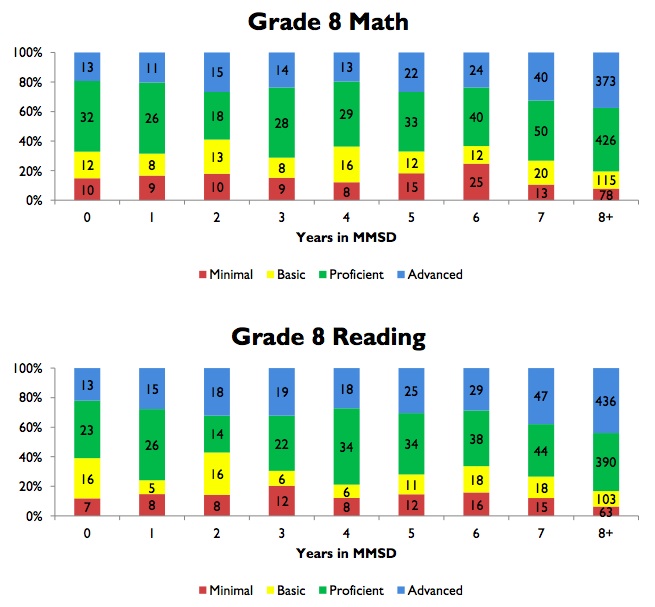

New NAEP data brings fresh round of questions on how to improve education

What are we doing wrong? Why aren’t things getting better?

No, I don’t have some powerful secret answer. But I know the urgency behind the questions became all the clearer last week, whether you’re talking about Milwaukee or Wisconsin as a whole. Whatever it is that would work, we haven’t done it yet or, at best, we haven’t done it well enough.

There are so many people trying to change education outcomes for the better. I respect so many of them and think some are having praiseworthy impact in specific arenas. But the overall pursuit? Look at the record.

There are two reasons for my fresh agitation:

First are new results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). NAEP is the best, most nailed-down gauge of how students are doing nationwide. About every two years, NAEP releases results from reading and math tests of samples of fourth and eighth graders in every state. New results came out Thursday.

Nationwide, there were some bright spots, but overall, not much was new or better.

For Wisconsin, the results were disheartening. The average score of a fourth grader in reading was lower than in 1992. We pride ourselves on being a high performing state, but the Wisconsin score and the national score were the same. Sounds pretty middle-of-the-pack to me.

There has been long-term improvement in math scores in Wisconsin. But almost all of it occurred years ago — scores have been flat for the last half-dozen years.

Indiana Community College Makes Studying Pay Off

The typical community-college student works at least part time while attending classes and often doesn’t complete a degree even after three years, according to the U.S. Education Department.

Derrick Johnson is on a different track. The 19-year-old first-year student from a low-income neighborhood of Indianapolis received a scholarship for spending six hours in class each day and another six hours a day studying with classmates. He has pledged not to work during the week. His scholarship, besides tuition and fees, also helps cover expenses, such as some food and transportation costs. Best of all, he expects to earn an associate’s degree by May, within one year.

Mr. Johnson sleeps on a couch at his dad’s house and rises at 5 a.m. He then rides two buses for about an hour to get to school each day by 7 a.m., and usually leaves campus by 7 p.m. His weekdays consist of little more than attending class, studying and commuting. Other students have more breathing room because they can drive to school, avoiding a lengthy trip on public transportation.

“It takes up a lot of time,” Mr. Johnson said. “But I can get stuff done in a year and the cost is less” than a traditional two-year associate’s degree.

Mr. Johnson is part of an experimental program at Ivy Tech Community College, a public community college in Indiana. The Associate Accelerated Program, known by the nickname ASAP, aims to chart a new path to a degree as two-year schools across the nation wrestle with poor graduation and retention rates and a growing need to upgrade the skills of people entering the workforce.

History Paralysis

When it comes to working together to support the survival and enjoyment of history for students in our schools, why are history teachers, as a group, as good as paralyzed?

Whatever the reason, in the national debates over nonfiction reading (history books, anyone?) and nonfiction writing for students in the schools, the voice of history teachers, at least in the wider conversation, has not been clearly heard.

Perhaps it could be because, as David Steiner, former Commissioner of Education in New York State, put it: “History is so politically toxic that no one wants to touch it.”

Have the bad feelings and fears raised over the ill-fated National History Standards which emerged from UCLA so long ago persisted and contributed to our paralysis in these national discussions?

Are we (I used to be one) too sensitive to the feelings of other members of the social studies universe? Are we too afraid that someone will say we have given insufficient space and emphasis to the sociology of the mound people of Ohio or the history and geography of the Hmong people or the psychology of the Apache and the Comanche? Or do we feel guilty, even though it is not completely our fault, that all of the Presidents of the United States have been, (so far), men?

I am concerned when the National Assessment of Educational Progress finds that 86% of our high school seniors scored Basic or Below on U.S. History, and I am appalled by stories of students, who, when asked to choose our Allies in World War II on a multiple-choice test, select Germany (both here and in the United Kingdom, I am told). After all, Germany is an ally now, they were probably an ally in World War II, right? So Presentism reaps its harvest of historical ignorance.

Of course there is always competition for time to give to subjects in schools. Various groups push their concerns all the time. Business people often argue that students should learn about the stock market at least, if not credit default swaps and the like. Other groups want other things taught. I understand that there is new energy behind the revival of home economics courses for our high school future homemakers.

But what my main efforts have been directed towards since 1987 is prevention of the need for remedial nonfiction reading and writing courses in college. My national research has found that most U.S. public high schools do not ask students to write a serious research paper, and I am convinced that, if a study were ever done, it would show that we send the vast majority of our high school graduates off without ever having assigned them a complete history book to read. Students not proficient in nonfiction reading and writing are at risk of not understanding what their professors are talking about, and are, in my view, more likely to drop out of college.

For all I know, book reports are as dead in the English departments as they are in History departments. In any case, most college professors express strong disappointment in the degree to which entering students are capable of reading the nonfiction books they are assigned and of writing the term papers that are assigned.

A study done by the Chronicle of Higher Education found that 90% of professors judge their students to be “not very well prepared” in reading, doing research, and writing.

I cannot fathom why we put off instruction in nonfiction books and term papers until college in so many cases. We start young people at a very early age in Pop Warner football and in Little League baseball, but when it comes to nonfiction reading and writing we seem content to wait until they are 18 or so.

For whatever reason, some students have not let our paralysis prevent them either from studying history or from writing serious history papers, and I have proof that they can do good work in history, if asked to do so. When I started The Concord Review in 1987, I hoped that students might send me 4,000-word research papers in history. By now, I have published, in 98 issues, 1,077 history research papers averaging 6,000 words, on a huge variety of topics, by high school students from 46 states and 38 other countries.

Some have been inspired by their history teachers, other by their history-buff parents, but a good number have been encouraged by seeing the exemplary work of their peers in print. Here are parts of two comments from authors–Kaitlin Marie Bergan: “When I first came across The Concord Review, I was extremely impressed by the quality of writing and the breadth of historical topics covered by the essays in it. While most of the writing I have completed for my high school history classes has been formulaic and limited to specified topics, The Concord Review motivated me to undertake independent research in the development of the American Economy. The chance to delve further into a historical topic was an incredible experience for me and the honor of being published is by far the greatest I have ever received. This coming autumn, I will be starting at Oxford University, where I will be concentrating in Modern History.” And Emma Curran Donnelly Hulse: “As I began to research the Ladies’ Land League, I looked to The Concord Review for guidance on how to approach my task. At first, I did check out every relevant book from the library, running up some impressive fines in the process, but I learned to skim bibliographies and academic databases to find more interesting texts. I read about women’s history, agrarian activism and Irish nationalism, considering the ideas of feminist and radical historians alongside contemporary accounts…Writing about the Ladies’ Land League, I finally understood and appreciated the beautiful complexity of history…In short, I would like to thank you not only for publishing my essay, but for motivating me to develop a deeper understanding of history. I hope that The Concord Review will continue to fascinate, challenge and inspire young historians for years to come.”

Lots of high school [and middle school] students are sitting out there, waiting to be inspired by their history teachers [and their peers] to read history books and to prepare their best history research papers, and lots of history teachers are out there, wishing there were a stronger and more optimistic set of arguments coming from a history presence in the national conversation about higher standards for nonfiction reading and writing in our schools.

—————————–

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

Why Local Educators Haven’t Heeded the Warnings in ‘A Nation at Risk’

Editor’s Note: Recently, six well-known AIR thought leaders including George Bohrnstedt, Beatrice Birman, David Osher, Jennifer O’Day, Terry Salinger, and Jane Hannaway posted blogs on the AIR website about A Nation at Risk. Gary Phillips, AIR Vice President and AIR Institute Fellow, joins these thinkers with his blog, “Why Local Educators Haven’t Heeded the Warnings in A Nation at Risk,” which we’ve reposted below.

For the last 30 years national education leaders have believed that our underachieving educational system has put our nation at risk. One persistent problem with that belief is that the international data examined by national policy makers to support the claim don’t match the state data reported to the local press and parents. International assessments generally show that the United States is, at best, in the middle of the pack among other industrialized nations while state data generally show that students are proficient and performing above average. No wonder the crisis experienced by policy makers doesn’t seem so urgent to local governors, boards of education, and parents. And no wonder local educators haven’t acted on what national policy makers consider crises.

A graph helps illustrate the problem. The beige bars represent the state performance in 2007 based on the data reported by states to the federal government under the 2001 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, also known as No Child Left Behind. Look at Tennessee, for example. In 2007, the state reported that 90 percent of its 4th graders were proficient in mathematics based on challenging performance standards established by the state.

The China Americans Don’t See

The 21st-century romance between America’s universities and China continues to blossom, with New York University opening a Shanghai campus last month and Duke to follow next year. Nearly 100 U.S. campuses host “Confucius Institutes” funded by the Chinese government, and President Obama has set a goal for next year of seeing 100,000 American students studying in the Middle Kingdom. Meanwhile, Peking University last week purged economics professor Xia Yeliang, an outspoken liberal, with hardly a peep of protest from American academics.

“During more than 30 years, no single faculty member has been driven out like this,” Mr. Xia says the day after his sacking from the university, known as China’s best, where he has taught economics since 2000. He’ll be out at the end of the semester. The professor’s case is a window into the Chinese academic world that America’s elite institutions are so eager to join–a world governed not by respect for free inquiry but by the political imperatives of a one-party state. Call it higher education with Chinese characteristics.

“All universities are under the party’s leadership,” Mr. Xia says by telephone from his Beijing home. “In Peking University, the No. 1 leader is not the president. It’s the party secretary of Peking University.”

Some data on education, religiosity, ideology, and science comprehension

Because the “asymmetry thesis” just won’t leave me alone, I decided it would be sort of interesting to see what the relationship was between a “science comprehension” scale I’ve been developing and political outlooks.

The “science comprehension” measure is a composite of 11 items from the National Science Foundation’s “Science Indicators” battery, the standard measure of “science literacy” used in public opinion studies (including comparative ones), plus 10 items from an extended version of the Cognitive Reflection Test, which is normally considered the best measure of the disposition to engage in conscious, effortful information processing (“System 2”) as opposed to intuitive, heuristic processing (“System 1”).

The items scale well together (α= 0.81) and can be understood to measure a disposition that combines substantive science knowledge with a disposition to use critical reasoning skills of the sort necessary to make valid inferences from observation. We used a version of a scale like this–one combining the NSF science literacy battery with numeracy–in our study of how science comprehension magnifies cultural polarization over climate change and nuclear power.

Is Music the Key to Success?

Joanne Lipman CONDOLEEZZA RICE trained to be a concert pianist. Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, was a professional clarinet and saxophone player. The hedge fund billionaire Bruce Kovner is a pianist who took classes at Juilliard. Multiple studies link music study to academic achievement. But what is it about serious music training […]

Skill up or lose out

For the first time, the Survey of Adult Skills allows us to directly measure the skills people currently have, not just the qualifications they once obtained. The results show that what people know and what they do with what they know has a major impact on their life chances. On average across countries, the median wage of workers who score at Level 4 or 5 in the literacy test – meaning that they can make complex inferences and evaluate subtle arguments in written texts – is more than 60% higher than the hourly wage of workers who score at or below Level 1 – those who can, at best, read relatively short texts and understand basic vocabulary. Those with poor literacy skills are also more than twice as likely to be unemployed. In short, poor skills severely limit people’s access to better-paying and more-rewarding jobs.

It works the same way for nations: The distribution of skills has significant implications for how the benefits of economic growth are shared within societies. Put simply, where large shares of adults have poor skills, it becomes difficult to introduce productivity-enhancing technologies and new ways of working. And that can stall improvements in living standards.

Proficiency in basic skills affects more than earnings and employment. In all countries, adults with lower literacy proficiency are far more likely than those with better literacy skills to report poor health, to perceive themselves as objects rather than actors in political processes, and to have less trust in others. In other words, we can’t develop fair and inclusive policies and engage with all citizens if a lack of proficiency in basic skills prevents people from fully participating in society.

How Heroin Is Invading America’s Schools

What have I become?” 23-year-old Andrew Jones asked his mom shortly before he died. “What’s happened to me?” A star high school athlete who went on to play Division I football for Missouri State University, Andrew was an honors student whom friends described as outgoing, charismatic, and loyal. He was also a heroin addict.

Never even a recreational drug user, Andrew had been the first to discourage friends at his Catholic high school from smoking pot. But his story is frighteningly typical of the current heroin epidemic among suburban American youth. It’s an issue made all the more timely by the recent heroin-related death of Glee star Cory Monteith, best known and beloved for playing squeaky-clean high school football star Finn Hudson.

What Cory and Andrew expose is that heroin isn’t at all what it used to be. Not only is the drug much more powerful than before (purity can be as high as 90 percent) but it’s also no longer limited to the dirty-needle, back-alley experience so many of us picture. Now it’s as easy as purchasing a pill, because that’s what heroin has become: a powder-filled capsule known as a button, designed to be broken open and snorted, that can be purchased for just $10. And it regularly is–on varsity sports teams, on Ivy League campuses, and in safe suburban neighborhoods.

A Report Card on Education Reform

I sat down last week in Washington with Arne Duncan, the secretary of education, and Mitch Daniels, the former Indiana governor and current Purdue University president, after they had met with several dozen chief executives of big companies to talk about education. Their meeting was at the office of the Business Roundtable, the corporate lobbying group, and joining us for the conversation was John Engler, the former Michigan governor who runs the Business Roundtable.

Neilson Barnard/Getty Images, for The New York Time Education Secretary Arne Duncan

Mr. Duncan is a Democrat, of course, and Mr. Daniels and Mr. Engler are Republicans. But they all sympathize with many of the efforts of the so-called education reform movement. I asked them whether the country’s education system was really in crisis and what mistakes school reformers had made. A lightly edited version of the first part of our conversation follows; the second part will appear on Economix on Thursday.

Leonhardt: You always hear we’re in crisis. But what is the bad news, and what is the good news, and are we making any progress?

Duncan: I do think we have a crisis. I do feel tremendous urgency. If you look at any international comparison – which in a global economy is much more important than 30 or 40 years ago – on no indicator are we anywhere near where we want to be. Whether it’s test scores or college graduation rates, whatever it is, we’re not close. So we’ve got a long way to go. That’s the challenge.

Why I am hopeful is we have seen some real progress. Some things are going the right way. The question is how do we accelerate that progress. College graduations rates are up some. High school graduation rates are up to 30-year highs, which is a big step in the right direction.

The African-American/Latino community is driving much of that improvement, which is very, very important. There is a huge reduction in the number of kids going to dropout factories. We are seeing real progress. The question is how do we get better faster.

Daniels: I am glad that the secretary didn’t pull any punches. I don’t know any other way to read it. In Indiana, we just had, by far, the best results we’ve ever seen in our state. Everything was up. The high-school graduation rate is up 10 percent in just four years. Test scores, advanced-placement scores too. But we’re just nowhere near where we need to be. And the competition is not standing still. So we need many more years of progress at the current rate, and it still maybe too slow. I’m afraid this is a half-empty analysis, but I think it’s an honest one.

Engler: The president of Purdue and the president of the Business Roundtable – we are the consumer groups here at the table. All the products of K-12 system are either going to go to the university or they are going to the work force. The military is not here, but they’re not very different.Related: Madison’s long time disastrous reading scores and wisconsin2.org

Commentary on Using Empty Milwaukee Public Schools’ Buildings

As I regularly pass by the former Malcolm X Academy that has been vacant for years, the words of a legendary African-American educator comes to mind:

“No schoolhouse has been opened for us that has not been filled.”

Booker T. Washington said that in 1896 during an address to urge white Americans to respect the desire by most African-American parents to seek the best possible education for their children.

Fast-forward to 2013 in Milwaukee, and the issue of vacant school buildings gives a pecular spin to Washington’s words. Back then, he could never have imagined the combination of bureaucracy and politics that has some educators scrambling to find spaces to fill with African-American students.

The campaign by a local private school funded by taxpayers to buy the former Malcolm X Academy at 2760 N. 1st St. has caused some in town to question why Milwaukee Public Schools hasn’t done more to turn closed school buildings into functioning houses of learning.

In particular, some conservatives question why MPS hasn’t been willing to sell valuable resources to school choice entities that are essentially their main competition for low-income minority students.

Actually, that stance seems valid from a business standpoint; why help out the folks trying to put you out of business?The City of Milwaukee: Put Children First!

St. Marcus is at capacity.

Hundreds of children are on waiting lists.

Over the past decade, St. Marcus Lutheran School in Milwaukee’s Harambee neighborhood has proven that high-quality urban education is possible. The K3-8th grade school has demonstrated a successful model for education that helps children and families from urban neighborhoods break the cycle of poverty and move on to achieve academic success at the post-secondary level and beyond.

By expanding to a second campus at Malcolm X, St. Marcus can serve 900 more students.WILL Responds to MPS on Unused Schools Issues

On Tuesday, Milwaukee Public Schools responded to WILL’s report, “MPS and the City Ignore State Law on Unused Property.” Here is WILL’s reply:

1. MPS’ response is significant for what it does not say. WILL’s report states that, right now, there are at least 20 unused school buildings that are not on the market – and practically all of these buildings have attracted interest from charter and choice schools. As far as its records reveal, MPS refuses to adopt basic business practices, such as keeping an updated portfolio of what is happening with its facilities. How is the public to know where things stand when it is not clear that MPS keeps tabs on them?

2. MPS thinks everything is okay because it has sold four buildings since 2011 and leases to MPS schools. MPS’ response is similar to a football team (we trust it would be the Bears) celebrating that they scored two touchdowns in a game – only to end up losing 55-14. Our report acknowledged that MPS had disposed of a few buildings, but when there are at least 20 empty buildings – and substantial demand for them – claiming credit for selling a few is a bit like a chronic absentee celebrating the fact that he usually comes in on Tuesdays. Children and taxpayers deserve better.Conservative group says MPS, city not selling enough empty buildings

A conservative legal group says that Milwaukee Public Schools is stalling on selling its empty school buildings to competing school operators that seek school facility space, and that the City of Milwaukee isn’t acting on a new law that gives it more authority to sell the district’s buildings.

The Wisconsin Institute for Law & Liberty, which supports many Republican causes, says its new report shows that MPS is preventing charter schools and private schools in the voucher program from purchasing empty and unused school buildings.

But MPS fired back yesterday, saying the legal group’s information omits facts and containts false claims.

For example, MPS Spokesman Tony Tagliavia said that this year, five previously unused MPS buildings are back in service as schools.

He said MPS has also sold buildings to high-performing charter schools. Charter operators it has sold to such as Milwaukee College Prep and the Hmong American Peace Academy are operating schools that are under the MPS umbrella, however, so the district gets to count those students as part of its enrollment.My entire career of close to 50 years has been focused on growing a business in and close to the city of Milwaukee. This is where I have my roots. I have followed education closely over these years.

The Aug. 17 Journal Sentinel had an interesting article about conflicting opinions on what the most viable use is for the former Malcolm X School, which closed over six years ago.

The Milwaukee School Board has proposed to have the city convert the site into a community center for the arts, recreation, low-income housing and retail stores. The cost to city taxpaying residences and businesses has not been calculated. Rising tax burdens have been a major factor in the flight to the suburbs and decline of major cities across our country.

St. Marcus Lutheran School is prepared to purchase Malcolm X for an appraised fair market value. St. Marcus is part of Schools That Can Milwaukee, which also includes Milwaukee College Prep and Bruce-Guadalupe Community School. Other participating high performing schools are Atonement Lutheran School, Notre Dame Middle School and Carmen High School of Science and Technology. Support comes from private donations after state allowances for voucher/choice students.

Their students go on to graduate from high school at a rate of over 90%, compared to approximately 60% at Milwaukee Public Schools. The acquisition of Malcolm X would give an additional 800 students the opportunity to attend a high performing school and reduce waiting lists at St. Marcus.

Should Students Use a Laptop in Class?

There’s a widely shared image on the Internet of a teacher’s note that says: “Dear students, I know when you’re texting in class. Seriously, no one just looks down at their crotch and smiles.”

College students returning to class this month would be wise to heed such warnings. You’re not as clever as you think–your professors are on to you. The best way to stay in their good graces is to learn what behavior they expect with technology in and around the classroom.

Let’s start with the million-dollar question: May computers (laptops, tablets, smartphones) be used in class? Some instructors are as permissive as parents who let you set your own curfew. Others are more controlling and believe that having your phone on means your brain is off and that relying on Google for answers results in a digital lobotomy.

Why do people view teaching as a ‘B-list’ job?

It happens a lot: I’ll introduce myself to a group of people I don’t know well, explaining that I’m a high school English teacher. And someone will invariably respond, “But you’re smart, what do you really want to do?” As backhanded compliments go, that one really rankles. What I find most irksome isn’t even the implication that my colleagues and I are typically mundane or that my work of the last decade has been a waste of my time. The most frustrating thing about hearing that I’m “too smart” for teaching is the counter-productive mentality about my profession that such a comment underscores.

In the early half of the 20th century, a bright woman’s best career option was to be a teacher. Now, thankfully, most every path is open to women, the only downside of which is the inevitable matriculation of top female graduates away from the field of teaching due to a plethora of other choices. This trend is compounded by the fact that teaching is now seen as a B-list job: Most top graduates of my college went into law, medicine, business, or academia. Those who did go into teaching, myself included, constantly encountered the assumption that this would be a short-term gig, the ubiquitous two-year foray (through Teach for America or the like) that would ultimately pad graduate school applications. For many, it was. Teaching wasn’t, and – 10 years later – still isn’t, seen as a “prestigious” career, even by liberal university graduates who would all agree that strong public education is an inviolable social good.

When Is College Worth It?

Today’s RealClearPolicy slate features a piece from Dylan Matthews of the Washington Post claiming that college is a good investment. It pushes back against arguments in the vein of critics like Charles Murray and Richard Vedder, who argue that too many people are going to college.

Several years ago, I wrote a few pieces for National Review outlining the Murray/Vedder view (here’s one from the website), but I hadn’t kept up with the debate, and Matthews’s piece features a lot of newer research on the subject. What follows isn’t necessarily a response, but more of an overview of the topic and a reconsideration of my views in light of the updated evidence. I have six main points to make.

1. It’s not about college, it’s about college-for-all.

Matthews spends a considerable amount of time explaining that attending college is a good idea for the average student. This is true — but to the best of my knowledge, no college critic disputes it. For a lot of high-paying jobs, you simply need a college degree, no matter how smart you are; today’s doctors, teachers, engineers, and so forth would not be nearly so well off if they’d stopped after high school.

What we argue is that not all students benefit from college the way that the average student does, and that efforts to draw even more students to college could do more harm than good, because such efforts are focused on students who today rationally decide that college isn’t for them. We especially bristle at the notion that America should aspire to send all students to college.

If You Sacrifice Your Child to Prove a Point about Public Education, You are a Bad Person

I have a never-ending fascination with the politics of education, principally because I drew the short end of the stick on that count. The district in which I attended school was (is) notoriously bad.

On multiple occasions, I can recall the State taking over the high school due to very poor test scores while also implementing some drastic measures, like removing administrators and scheduling mandatory reading/writing times in unrelated classes like Geometry or Physical Education.

I was so deeply affected by my education due to the inherent contradiction between what I experienced and what people told me I was experiencing.

On the one hand, I had teachers and family telling me that those were the best years of my life, that I was doing something noble and important, that I was being paid for attendance in a currency much more valuable than money-experience, knowledge, wisdom.

On the other hand, I spent most of my weekdays bored out of my mind or overly anxious about something of little consequence. I learned to game the system, doing just enough to satisfy whatever was required of me without devoting myself fully to what I ultimately found to be futile and asinine and an incredible waste of time. I never could believe those were the best years of my life. If I’d thought that had been the pinnacle of my existence, I’d have offed myself years ago.

So, that being the case, I have no sympathy for public education. It caused me nothing but trouble while blaming me for its own trouble. I don’t mean to say all public education is incompetent and ineffective (though perhaps most of it is). I only mean to give some background on why I’m opposed to the ideas presented in Allison Benedikt’s If You Send Your Kid to Private School, You are a Bad Persona.

Academy Fight Song: “There is no Santa Claus”

his essay starts with utopia–the utopia known as the American university. It is the finest educational institution in the world, everyone tells us. Indeed, to judge by the praise that is heaped upon it, the American university may be our best institution, period. With its peaceful quadrangles and prosperity-bringing innovation, the university is more spiritually satisfying than the church, more nurturing than the family, more productive than any industry.

The university deals in dreams. Like other utopias–like Walt Disney World, like the ambrosial lands shown in perfume advertisements, like the competitive Valhalla of the Olympics–the university is a place of wish fulfillment and infinite possibility. It is the four-year luxury cruise that will transport us gently across the gulf of class. It is the wrought-iron gateway to the land of lifelong affluence.

It is not the university itself that tells us these things; everyone does. It is the president of the United States. It is our most respected political commentators and economists. It is our business heroes and our sports heroes. It is our favorite teacher and our guidance counselor and maybe even our own Tiger Mom. They’ve been to the university, after all. They know.

When we reach the end of high school, we approach the next life, the university life, in the manner of children writing letters to Santa. Oh, we promise to be so very good. We open our hearts to the beloved institution. We get good grades. We do our best on standardized tests. We earnestly list our first, second, third choices. We tell them what we want to be when we grow up. We confide our wishes. We stare at the stock photos of smiling students, we visit the campus, and we find, always, that it is so very beautiful.

And when that fat acceptance letter comes–oh, it is the greatest moment of personal vindication most of us have experienced. Our hard work has paid off. We have been chosen.

Then several years pass, and one day we wake up to discover there is no Santa Claus. Somehow, we have been had. We are a hundred thousand dollars in debt, and there is no clear way to escape it. We have no prospects to speak of. And if those damned dreams of ours happened to have taken a particularly fantastic turn and urged us to get a PhD, then the learning really begins.

The disaster that the university has proceeded to inflict on the youth of America, I submit, is the direct and inescapable outcome of this grim equation. Yes, in certain reaches of the system the variables are different and the yield isn’t quite as dreadful as in others. But by and large, once all the factors I have described were in place, it was a matter of simple math. Grant to an industry control over access to the good things in life; insist that it transform itself into a throat-cutting, market-minded mercenary; get thought leaders to declare it to be the answer to every problem; mute any reservations the nation might have about it–and, lastly, send it your unsuspecting kids, armed with a blank check drawn on their own futures.

Was it not inevitable? Put these four pieces together, and of course attendance costs will ascend at a head-swimming clip, reaching $60,000 a year now at some private schools. Of course young people will be saddled with life-crushing amounts of debt; of course the university will use its knowledge of them–their list of college choices, their campus visits, their hopes for the future–to extract every last possible dollar from the teenage mark and her family. It is lambs trotting blithely to the slaughter. It is the utterly predictable fruits of our simultaneous love affairs with College and the Market. It is the same lesson taught us by so many other disastrous privatizations: in our passion for entrepreneurship and meritocracy, we forgot that maybe the market wasn’t the solution to all things.

UW Law School 2013 Graduation Speech

Judge Barbara Crabb (PDF), via a kind Susan Vogel email:

Dear Raymond, new graduates and their proud guests.

I start today with rousing congratulations to the new graduates.

I realize that some of you may be thinking that condolences are more in order, but I don’t agree. Yes, the market is not great for new lawyers. Yes, many of you have large student loans to worry about. But you are the holders of a degree many people can only dream of acquiring. And that degree is more than a piece of paper. It is evidence that you think differently today–you’ve been taught to do so critically and analytically. You attack problems differently because you have new tools for doing so. You demand proof of propositions you used to take for granted. Best of all, you understand that every complicated problem will, when properly studied, turn out to be even more complicated.

You’ve had three years of study with some great teachers. They’ve opened your minds to new possibilities. They’ve forced you to think harder than you thought you ever could. You may have worked on a law review. You may have taken part in moot problems you might never have imagined. You may have had internships–some of which were in federal court, which has given me a chance to get to know you– and those have enabled you to put into practice your classroom learning. And now, after what loomed as an eternity three years ago, you’re joining the ranks of the legal profession.

Many people have contributed to make this day a reality: parents, spouses, partners, teachers, professors, friends, the taxpayers of the state of Wisconsin. All of them believe that their investment in you is a valuable one.

Yes, the future is uncertain. But uncertainty is a fact of life. I can assure you that you are not the first or the last class to graduate into uncertainty. I always keep in mind that Nathan Heffernan, who was chief justice of the Wisconsin Supreme Court from 1983 to 1995, started his career in the only job he could find at the time of his law school graduation, which was as an insurance claims adjuster.

What is certain is that the world as we know it today will not be the world of tomorrow.

Fifty years ago, people graduating from law school were worried about the war in between the words of the Constitution and the reality of life for so many of the nation’s citizens, but they had no idea of the protests that would take place in a few years as more people began to claim their rightful place in American society. In 1963, those graduates were mostly unaware of the civil rights movement that was simmering in Nashville and that would eventually change our country forever.

The world you are entering is in its usual and fractious state, although the causes and the disagreements are different. It seems possible that governmental functions will reach a permanent condition of stasis unless courageous and enlightened people can find areas in which they can cooperate and compromise. The middle east poses a multitude of threats and opportunities, as do many other areas of the world. The widening income gap in the United States is worrisome, as is the diminution of personal privacy.

The point is that life is never settled or determinable in advance. The next fifty years are as unknowable to you as the last fifty were in 1963 to those, like me, who graduated from law school then. None of us graduates with a script; we all improvise and adjust as we perform our roles in a play in which there are no rehearsals, often finding about.

But it is this very uncertainty for which lawyers are trained. Big challenges, seemingly insoluble problems, conflict of all kinds, confrontations–they’re all grist for the lawyer’s mill. Mediating disagreements, finding common ground, defending the rights of minorities, holding those in power accountable when they abuse their power, finding solutions to problems, helping businesses grow, expand and create jobs, advising nonprofit corporations, defending the Constitution–that’s what your training has prepared you to do.

It is wholly improbable that lawyers will be underemployed for long, given the need for them in every area. With your law degree, you have skills too valuable to go unused for long. Some of you will find those skills indispensable in a job outside the legal profession; some of you will take the more traditional routes of working for a firm, or the government or a nonprofit organization providing legal services. Some of you will end up teaching. Some of you will make your contribution in politics, a field perennially in need of smart, well educated lawyers who understand the world and the Constitution about finding work.

You may have to be innovators and the inventors of your own jobs, as the media keeps predicting. That seems to be part of the future: the stars of the future will be those who can invent not just new products but whole new ways of working.

For those of you with these skills, I challenge you. Imagine a way of integrating technology with legal skills and information. Think about providing legal help to the hundreds of thousands, even millions, of people in our country who need lawyers and cannot afford them. It is a daunting challenge, especially because the only way to make it work is to make it profitable. But it is enormously important.

How can it be good for a democracy to have the kind of mismatch between legal needs and underutilized lawyers that we do? Consider these realities:

The vast majority of people seeking a divorce are unrepresented.

Parents who face the loss of their children in court actions to terminate parental rights have no right to appointed counsel.

Few persons facing foreclosure have counsel, including members of the armed

forces while they are deployed. Legal aid agencies are overworked and lack the funding to add lawyers.

It is clear that the present fee-for-service model isn’t working for these people. It is also clear that reliance on governmental or philanthropic funding is not an answer. We know how untreated medical problems can drag people down; unfilled legal needs can have the same effect. This country needs to learn how to help the millions of people whose lives could be improved and who could be contributors to society if their legal problems were be resolved.

Perhaps it’s time to rethink the assumption that legal services always have to be individualized. Maybe ideas like LegalZoom.com an answer–or at least a marker on the road to something better. Are there other, better ways of delivering and paying for legal services?

I challenge you to come up with new ideas for other problems and to question everything. Does law school have to be three years long? Should lawyers continue to better ways to organize and provide legal services? Can courts be more effective and productive? Are the prison and probation systems doing as good a job as they could of reducing crime rates and turning out offenders ready to take their proper place in the community?

You are in the position to take a fresh look at what is not working as well as it could be in our country. You can help effect change. You can do your part in making the words of the Constitution a reality for more people. You have the legal education and you have a big advantage most of us older lawyers do not, which is an innate awareness of the possibilities of electronic media.

On a personal note, my wish for each of you is to find work to do that will engage all of your talents, provide you challenges and satisfaction, free you from the shadow of debt–and even give you time for a life.

The law has given me unimaginable opportunities. From the vantage point of the judge’s bench, I have seen drama more exciting than any movie; I have seen lawyers of amazing talent. I have had fascinating cases to decide (along with many not so fascinating); some of these cases have been of great interest to the public; others have been important only to the parties. I have learned more about our society than I would have thought possible, about criminal schemes to defraud, about drug conspiracies, about family feuds over money and property, about patent litigation and about all forms of discrimination. I have had a glimpse into the unimaginable misery of the lives of some of the poorest and most deprived members of our society and have seen as well bits of the lives of some of the most fortunate and prominent members. I have seen firsthand how important the law is to people at every level of society and how every person values fairness and a chance to be vindicated. I have seen how lawyers have given them that chance and how hard the lawyers have worked in doing so.

I still believe that the law is an honorable profession and that those who practice it are among the luckiest people I know. Even with its flaws and shortcomings, it remains the bulwark of our society. I hope that you, too, will find your careers rewarding. I hope you will continue the work of your predecessors in improving the profession and in making legal services more accessible to more people. Good luck and congratulations.

M. Night Shyamalan Takes on Education Reform

M. Night Shyamalanhas spent most of his career as a filmmaker coming up with supernatural plotlines and creepy characters, but these days, he says, he’s got a different sort of fantasy character in mind: Clark Kent, the nerdy, bookish counterpart to the glamorous, highflying Superman.

Best known for producing films such as “The Sixth Sense” and “The Village,” Mr. Shyamalan is about to come out with a book called “I Got Schooled” on the unlikely subject of education reform. He’s the first to admit what a departure it is from his day job. “When you say ‘ed reform’ my eyes glaze over,” Mr. Shyamalan says, laughing. “I was going to have some provocative title like ‘Sex, Scandals and Drugs,’ and then at the bottom say: ‘No, really this is about ed reform.”

…….

Until recently, he says, moviemaking was his real passion. “I’m not a do-gooder,” he says. Still, after the commercial success of his early movies, he wanted to get involved in philanthropy. At first, he gave scholarships to inner-city children in Philadelphia, but he found the results disheartening. When he met the students he had supported over dinner, he could see that the system left them socially and academically unprepared for college. “They’d been taught they were powerless,” he says.

He wanted to do more. He decided to approach education like he did his films: thematically. “I think in terms of plot structure,” he says. He wondered if the problems in U.S. public schools could be traced to the country’s racial divisions. Because so many underperforming students are minorities, he says, “there’s an apathy. We don’t think of it as ‘us.’ ”

One reason that countries such as Finland and Singapore have such high international test scores, Mr. Shyamalan thinks, is that they are more racially homogenous. As he sees it, their citizens care more about overall school performance–unlike in the U.S., where uneven school quality affects some groups more than others. So Mr. Shyamalan took it upon himself to figure out where the education gap between races was coming from and what could be done about it.

An idea came to him over dinner with his wife and another couple who were both physicians. One of them, then the chief resident at a Pennsylvania hospital, said that the first thing he told his residents was to give their patients several pieces of advice that would drastically increase their health spans, from sleeping eight hours a day to living in a low-stress environment. The doctor emphasized that the key thing was doing all these things at the same time–not a la carte.

“That was the click,” says Mr. Shyamalan. It struck him that the reason the educational research was so inconsistent was that few school districts were trying to use the best, most proven reform ideas at once. He ultimately concluded that five reforms, done together, stand a good chance of dramatically improving American education. The agenda described in his book is: Eliminate the worst teachers, pivot the principal’s job from operations to improving teaching and school culture, give teachers and principals feedback, build smaller schools, and keep children in class for more hours.

Over the course of his research, Mr. Shyamalan found data debunking many long-held educational theories. For example, he found no evidence that teachers who had gone through masters programs improved students’ performance; nor did he find any confirmation that class size really mattered. What he did discover is plenty of evidence that, in the absence of all-star teachers, schools were most effective when they put in place strict, repetitive classroom regimens.Ah, content knowledge!

Science Is Not Your Enemy An impassioned plea to neglected novelists, embattled professors, and tenure-less historians

The great thinkers of the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment were scientists. Not only did many of them contribute to mathematics, physics, and physiology, but all of them were avid theorists in the sciences of human nature. They were cognitive neuroscientists, who tried to explain thought and emotion in terms of physical mechanisms of the nervous system. They were evolutionary psychologists, who speculated on life in a state of nature and on animal instincts that are “infused into our bosoms.” And they were social psychologists, who wrote of the moral sentiments that draw us together, the selfish passions that inflame us, and the foibles of shortsightedness that frustrate our best-laid plans.

These thinkers–Descartes, Spinoza, Hobbes, Locke, Hume, Rousseau, Leibniz, Kant, Smith–are all the more remarkable for having crafted their ideas in the absence of formal theory and empirical data. The mathematical theories of information, computation, and games had yet to be invented. The words “neuron,” “hormone,” and “gene” meant nothing to them. When reading these thinkers, I often long to travel back in time and offer them some bit of twenty-first-century freshman science that would fill a gap in their arguments or guide them around a stumbling block. What would these Fausts have given for such knowledge? What could they have done with it?

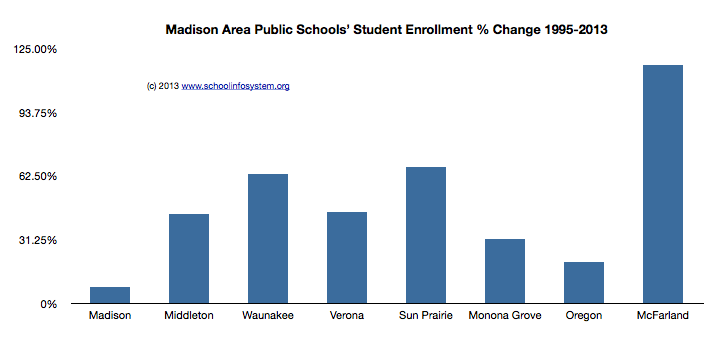

“The School District of Choice in Dane County”

MMSD School Board President Ed Hughes said that public education these days is under a lot of pointed criticism if not under an outright attack. “Initiatives like the voucher expansion program are premised on the notion that urban traditional public schools are not up to the task of effectively educating a diverse body of students,” Hughes says. “We’re out to prove that they are wrong. We agree with Superintendent Cheatham that in Madison all of the pieces are in place for us to be successful. Following the framework that she will describe to you, we set the goal for ourselves to be the model of a thriving urban school district that is built on strong community partnerships as well as genuine collaboration of teachers and staff. As we do that, we will be the school district of choice in Dane County.”

Cheatham said that Madison has a lot of great things going for it, but also had its share of challenges.

“A continually changing set of priorities has made it difficult for our educators to remain focused on the day-to-day work of teaching and learning, a culture of autonomy that has made it difficult to guaranteed access to a challenging curriculum for all students,” Cheatham said. “The system is hard for many of our students to navigate which results in too many of our students falling through the cracks.”

It starts with a simple but bold vision that every school is a thriving school that prepares every student for college, career, and community. “From now on, we will be incredibly focused on making that day-to-day vision become a reality,” she said.

“Many districts create plans at central office and implement them from the top down. Instead, schools will become the driving force of change in Madison,” Cheatham said. “Rather than present our educators with an ever-changing array of strategies, we will focus on what we know works — high quality teaching, coherent instruction, and strong leadership — and implement these strategies extremely well.”Related: The Dichotomy of Madison School Board Governance: “Same Service” vs. “having the courage and determination to stay focused on this work and do it well is in itself a revolutionary shift for our district”.

“The notion that parents inherently know what school is best for their kids is an example of conservative magical thinking.”; “For whatever reason, parents as a group tend to undervalue the benefits of diversity in the public schools….”.

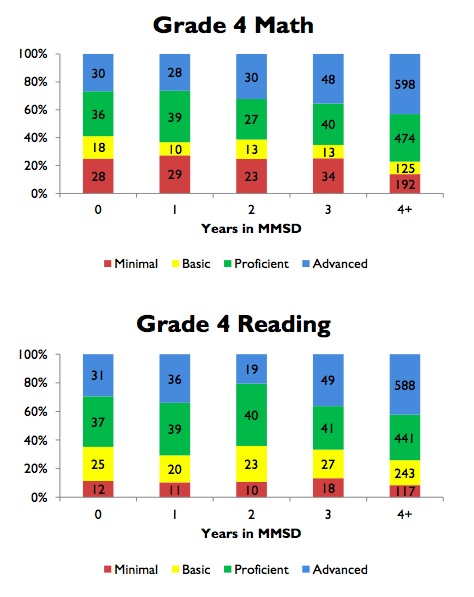

Madison’s long term, disastrous reading results.

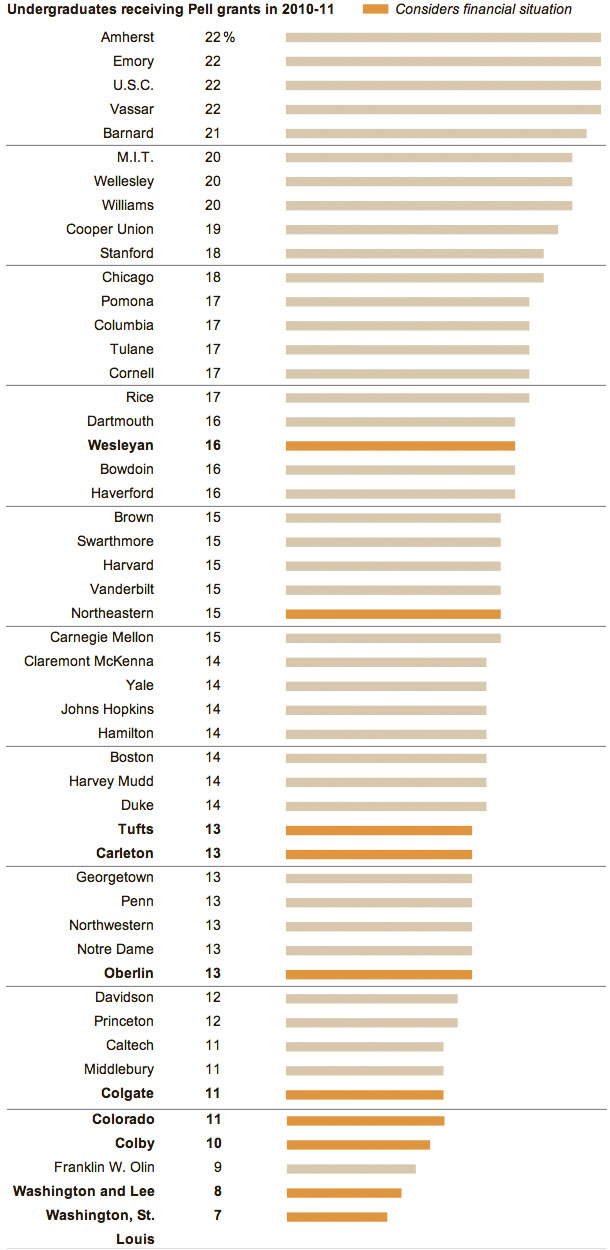

Efforts to Recruit Poor Students Lag at Some Elite Colleges

With affirmative action under attack and economic mobility feared to be stagnating, top colleges profess a growing commitment to recruiting poor students. But a comparison of low-income enrollment shows wide disparities among the most competitive private colleges. A student at Vassar, for example, is three times as likely to receive a need-based Pell Grant as one at Washington University in St. Louis.

“It’s a question of how serious you are about it,” said Catharine Bond Hill, the president of Vassar. She said of colleges with multibillion-dollar endowments and numerous tax exemptions that recruit few poor students, “Shame on you.”

At Vassar, Amherst College and Emory University, 22 percent of undergraduates in 2010-11 received federal Pell Grants, which go mostly to students whose families earn less than $30,000 a year. The same year, the most recent in the federal Department of Education database, only 7 percent of undergraduates at Washington University were Pell recipients, and 8 percent at Washington and Lee University were, according to research by The New York Times.

Researchers at Georgetown University have found that at the most competitive colleges, only 14 percent of students come from the lower 50 percent of families by income. That figure has not increased over more than two decades, an indication that a generation of pledges to diversify has not amounted to much. Top colleges differ markedly in how aggressively they hunt for qualified teenagers from poorer families, how they assess applicants who need aid, and how they distribute the available aid dollars.

Some institutions argue that they do not have the resources to be as generous as the top colleges, and for most colleges, with meager endowments, that is no doubt true. But among the elites, nearly all of them with large endowments, there is little correlation between a university’s wealth and the number of students who receive Pell Grants, which did not exceed $5,550 per student last year.

Related:Travis Reginal and Justin Porter were friends back in Jackson, Miss. They attended William B. Murrah High School, which is 97 percent African-American and 67 percent low income. Murrah is no Ivy feeder. Low-income students rarely apply to the nation’s best colleges. But Mr. Reginal just completed a first year at Yale, Mr. Porter at Harvard. Below, they write about their respective journeys.

Reflections on the Road to Yale: A First-Generation Student Striving to Inspire Black Youth by Travis Reginal:For low-income African-American youth, the issue is rooted in low expectations. There appear to be two extremes: just getting by or being the rare gifted student. Most don’t know what success looks like. Being at Yale has raised my awareness of the soft bigotry of elementary and high school teachers and administrators who expect no progress in their students. At Yale, the quality of your work must increase over the course of the term or your grade will decrease. It propelled me to work harder.

Reflections on the Road to Harvard: A Classic High Achiever, Minus the Money for a College Consultant by Justin Porter

I do not believe that increasing financial aid packages and creating glossy brochures alone will reverse this trend. The true forces that are keeping us away from elite colleges are cultural: the fear of entering an alien environment, the guilt of leaving loved ones alone to deal with increasing economic pressure, the impulse to work to support oneself and one’s family. I found myself distracted even while doing problem sets, questioning my role at this weird place. I began to think, “Who am I, anyway, to think I belong at Harvard, the alma mater of the Bushes, the Kennedys and the Romneys? Maybe I should have stayed in Mississippi where I belonged.”

Teacher training program uses rigorous preparation to produce great instructors

Ben Velderman The Match Education organization has developed a reputation over the past 12 years for operating several high-quality charter schools throughout the Boston area. Now the organization is garnering national attention for its approach to training future teachers. It all began in 2008, when Match officials opened a two-year teacher training program for graduate […]

Kennedy Center picks Madison for arts education push

All young children in Madison public schools would have greater access to the arts under a program being launched in the city this fall by the Kennedy Center.

The Washington, D.C.-based Kennedy Center — best known as a national showcase and landmark hub of the arts — has selected Madison as the 12th U.S. city for its “Any Given Child” program. The initiative is designed to create a long-range arts education plan to reach every public school student in grades K-8.

“The (Madison) district has specific goals about closing the achievement gap, and we know that the arts can help achieve that,” said Ray Gargano, director of programming and community engagement for the Overture Center for the Arts, which is coordinating the local side of Any Given Child.

In the first year of the multi-year program, two representatives from the Kennedy Center will assist a committee of about 35 local citizens to audit the arts resources in every Madison elementary and middle school, said Darrell Ayers, vice-president of education for the Kennedy Center.

That information will be used to create a long-term plan to make sure healthy arts programs are happening in every school for every child, not just some.

“The next two or three years (following the audit), we stay with the community to assure that the work is going to be completed,” Ayers said. “We’re not bringing money, but we’re certainly bringing expertise. We’ve done this in a number of communities and been very successful.”

Statistics: Male Students Are Falling Behind

Our great nation is known for the constant pursuit of equality and for “offering every citizen “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” In education, while there is an increasing focus on minority achievement, especially for African American and Hispanic students, few people are acknowledging the growing disparity in gender achievement in the United States.

According to New York Times bestselling author Michael Gurian, for every 100 girls suspended from elementary and secondary school, 250 boys are suspended. For every 100 girls diagnosed with a learning disability, 276 boys are so diagnosed. Also, for every 100 girls expelled from school, 355 boys are expelled.

Similarly, boys are expelled from preschool at five times the rate of girls, and boys are 60% more likely to be held back in kindergarten than girls. More girls than boys take college prep courses in high school and take the SAT. On average, girls get better grades than boys and graduate with high GPA’s. Considering these statistics it is not at all surprising that more girls receive college degrees.

In his book, Why Boys Fail, Richard Whitmire reports that the reading skills of the average 17-year-old boy have steadily declined over the last 20 years. According to estimates, if 5% more boys completed high school and matriculated to college, the nation would save $8 billion a year in welfare and criminal justice costs.

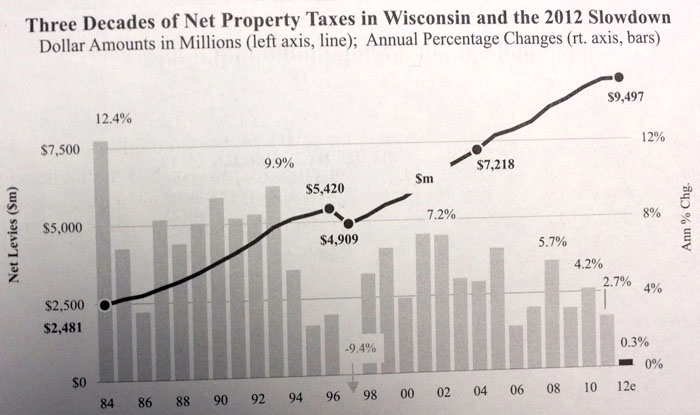

Madison’s Proposed Property Tax Increase: Additional links, notes and emails

I received a kind email from Madison School Board President Ed Hughes earlier today regarding the proposed property tax increase associated with the 2013-2014 District budget.

Ed’s email:Jim —

Your comparison to the tax rates in Middleton is a bit misleading. The Middleton-Cross Plains school district that has a mill rate that is among the lowest in Dane County. I am attaching a table (.xls file) that shows the mill rates for the Dane County school districts. As you will see, Madison’s mill rate is lower than the county average, though higher than Middleton’s. (Middleton has property value/student that is about 10% higher than Madison, which helps explain the difference.)

The table also includes the expenses/student figures relied upon by DPI for purposes of calculating general state aid for the 2012-13 school year. You may be surprised to see that Madison’s per-student expenditures as measured for these purposes is among the lowest in Dane County. Madison’s cost/student expenditures went up in the recently-completed school year, for reasons I explain here: http://tinyurl.com/obd2wty

EdMy followup email:

Hi Ed:

Thanks so much for taking the time to write and sending this along – including your helpful post.

I appreciate and will post this information.

That said, and as you surely know, “mill rate” is just one part of the tax & spending equation:

1. District spending growth driven by new programs, compensation & step increases, infinite campus, student population changes, open enrollment out/in,

2. ongoing “same service” governance, including Fund 80,

3. property tax base changes (see the great recession),

4. exempt properties (an issue in Madison) and

5. growth in other property taxes such as city, county and tech schools.

Homeowners see their “total” property taxes increasing annually, despite declining to flat income. Middleton’s 16% positive delta is material and not simply related to the “mill rate”.

Further, I continue to be surprised that the budget documents fail to include total spending. How are you evaluating this on a piecemeal basis without the topline number? – a number that seems to change every time a new document is discussed.

Finally, I would not be quite as concerned with the ongoing budget spaghetti if Madison’s spending were more typical for many districts along with improved reading results. We seem to be continuing the “same service” approach of spending more than most and delivering sub-par academic results for many students. (Note the recent expert review of the Madison schools Analysis: Madison School District has resources to close achievement gap.)

That is the issue for our community.

Best wishes,

Jim

Related: Middleton-Cross Plains’ $91,025,771 2012-2013 approved budget (1.1mb PDF) for 6,577 students, or $13,840.01 per student, roughly 4.7% less than Madison’s 2012-2013 spending.

Work to improve ALL schools in Milwaukee

Abby Andrietsch and Kole Knueppel, via several kind reader emails:

Charter. Choice. Public.

In recent weeks, these words became more politically charged than ever before. They are emblematic of the divisive debate surrounding school funding and policy changes included in the new state budget.

Now, the time for discussion and deliberation is over. The budget is law. It is time for Milwaukee’s education stakeholders to move forward and to do so together for the benefit of all our city’s children — no matter what type of school they attend. For the sake of our city’s prosperity and quality of life today and in the future, we must turn our collective efforts toward improving the quality of all schools.

Despite decades of effort, too many Milwaukee children still lack access to an effective, high-quality education. In fact, we have the largest racial achievement gap in the country. Without the opportunity to attend an excellent school, students will continue to fall behind, their challenges compounding into insurmountable roadblocks to success in academics and life.

In Milwaukee, there are great Milwaukee Public Schools, choice schools and charter schools. Still, each of these categories contains some of the worst schools in our community. Instead of bickering over how schools are organized, we need more collaboration and sharing of best practices across all three sectors. We need to work together to ensure that every type of school is capable of equipping students for the future.

Since 2010, Schools That Can Milwaukee has partnered with and supported high-quality and high-potential schools across all three sectors to close the Milwaukee achievement gap and ensure all students have the opportunity to learn and succeed. By focusing on kids and quality instead of the differences between school types, STCM is leading an unprecedented cross-sector collaboration of talented leaders from MPS, charter and choice schools serving predominantly low-income students.

Over the past three years, schools supported by STCM have outperformed their Milwaukee peers on the annual standardized Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Exam, and many also have beaten state test score averages. During the 2013-’14 school year, STCM will work with 35 traditional MPS, charter and choice schools, supporting more than 150 school and teacher leaders reaching over 13,000 students. Not only are these leaders coming together with a vision of excellence for their own schools, but also a larger vision of quality for our community and our children.

A Game-Changing Education Book from England

Our educators now stand ready to commit the same mistakes with the Common Core State Standards. Distressed teachers are saying that they are being compelled to engage in the same superficial, content-indifferent activities, given new labels like “text complexity” and “reading strategies.” In short, educators are preparing to apply the same skills-based notions about reading that have failed for several decades.

E. D. Hirsch, Jr.A British schoolteacher, Daisy Christodoulou, has just published a short, pungent e-book called Seven Myths about Education. It’s a must-read for anyone in a position to influence our low-performing public school system. The book’s focus is on British education, but it deserves to be nominated as a “best book of 2013″ on American education, because there’s not a farthing’s worth of difference in how the British and American educational systems are being hindered by a slogan-monopoly of high-sounding ideas–brilliantly deconstructed in this book.

Ms. Christodoulou has unusual credentials. She’s an experienced classroom teacher. She currently directs a non-profit educational foundation in London, and she is a scholar of impressive powers who has mastered the relevant research literature in educational history and cognitive psychology. Her writing is clear and effective. Speaking as a teacher to teachers, she may be able to change their minds. As an expert scholar and writer, she also has a good chance of enlightening administrators, legislators, and concerned citizens.

Ms. Christodoulou believes that such enlightenment is the great practical need these days, because the chief barriers to effective school reform are not the usual accused: bad teacher unions, low teacher quality, burdensome government dictates. Many a charter school in the U.S. has been able to bypass those barriers without being able to produce better results than the regular public schools they were meant to replace. No wonder. Many of these failed charter schools were conceived under the very myths that Ms. Christodoulou exposes. It wasn’t the teacher unions after all! Ms. Christodoulou argues convincingly that what has chiefly held back school achievement and equity in the English-speaking world for the past half century is a set of seductive but mistaken ideas.

She’s right straight down the line. Take the issue of teacher quality. The author gives evidence from her own experience of the ways in which potentially effective teachers have been made ineffective because they are dutifully following the ideas instilled in them by their training institutes. These colleges of education have not only perpetuated wrong ideas about skills and knowledge, but in their scorn for “mere facts” have also deprived these potentially good teachers of the knowledge they need to be effective teachers of subject matter. Teachers who are only moderately talented teacher can be highly effective if they follow sound teaching principles and a sound curriculum within a school environment where knowledge builds cumulatively from year to year.

Here are Ms Christodoulou’s seven myths:

1 – Facts prevent understanding

2 – Teacher-led instruction is passive

3 – The 21st century fundamentally changes everything

4 – You can always just look it up

5 – We should teach transferable skills

6 – Projects and activities are the best way to learn

7 – Teaching knowledge is indoctrination

Each chapter follows the following straightforward and highly effective pattern. The “myth” is set forth through full, direct quotations from recognized authorities. There’s no slanting of the evidence or the rhetoric. Then, the author describes concretely from direct experience how the idea has actually worked out in practice. And finally, she presents a clear account of the relevant research in cognitive psychology which overwhelmingly debunks the myth. Ms. Christodoulou writes: “For every myth I have identified, I have found concrete and robust examples of how this myth has influenced classroom practice across England. Only then do I go on to show why it is a myth and why it is so damaging.”

This straightforward organization turns out to be highly absorbing and engaging. Ms. Christodoulou is a strong writer, and for all her scientific punctilio, a passionate one. She is learned in educational history, showing how “21st-century” ideas that invoke Google and the internet are actually re-bottled versions of the late 19th-century ideas which came to dominate British and American schools by the mid-20th century. What educators purvey as brave such as “critical-thinking skills” and “you can always look it up” are actually shopworn and discredited by cognitive science. That’s the characteristic turn of her chapters, done especially effectively in her conclusion when she discusses the high-sounding education-school theme of hegemony:

I discussed the way that many educational theorists used the concept of hegemony to explain the way that certain ideas and practices become accepted by people within an institution. Hegemony is a useful concept. I would argue that the myths I have discussed here are hegemonic within the education system. It is hard to have a discussion about education without sooner or later hitting one of these myths. As theorists of hegemony realise, the most powerful thing about hegemonic ideas is that they seem to be natural common sense. They are just a normal part of everyday life. This makes them exceptionally difficult to challenge, because it does not seem as if there is anything there to challenge. However, as the theorists of hegemony also realised, hegemonic ideas depend on certain unseen processes. One tactic is the suppression of all evidence that contradicts them. I trained as a teacher, taught for three years, attended numerous in-service training days, wrote several essays about education and followed educational policy closely without ever even encountering any of the evidence about knowledge I speak of here, let alone actually hearing anyone advocate it….For three years I struggled to improve my pupils’ education without ever knowing that I could be using hugely more effective methods. I would spend entire lessons quietly observing my pupils chatting away in groups about complete misconceptions and I would think that the problem in the lesson was that I had been too prescriptive. We need to reform the main teacher training and inspection agencies so that they stop promoting completely discredited ideas and give more space to theories with much greater scientific backing.

The book has great relevance to our current moment, when a majority of states have signed up to follow new “Common Core Standards,” comparable in scope to the recent experiment named “No Child Left Behind,” which is widely deemed a failure. If we wish to avoid another one, we will need to heed this book’s message. The failure of NCLB wasn’t in the law’s key provisions that adequate yearly progress in math and reading should occur among all groups, including low-performing ones. The result has been some improvement in math, especially in the early grades, but stasis in most reading scores. In addition, the emphasis on reading tests has caused a neglect of history, civics, science, and the arts.

Ms. Christodoulou’s book indirectly explains these tragic, unintended consequences of NCLB, especially the poor results in reading. It was primarily the way that educators responded to the accountability provisions of NCLB that induced the failure. American educators, dutifully following the seven myths, regard reading as a skill that could be employed without relevant knowledge; in preparation for the tests, they spent many wasted school days on ad hoc content and instruction in “strategies.” If educators had been less captivated by anti-knowledge myths, they could have met the requirements of NCLB, and made adequate yearly progress for all groups. The failure was not in the law but in the myths.

Our educators now stand ready to commit the same mistakes with the Common Core State Standards. Distressed teachers are saying that they are being compelled to engage in the same superficial, content-indifferent activities, given new labels like “text complexity” and “reading strategies.” In short, educators are preparing to apply the same skills-based notions about reading that have failed for several decades.

Of course! They are boxed in by what Ms. Christodoulou calls a “hegemonic” thought system. If our hardworking teachers and principals had known what to do for NCLB– if they had been uninfected by the seven myths–they would have long ago done what is necessary to raise the competencies of all students, and there would not have been a need for NCLB. If the Common Core standards fail as NCLB did, it will not be because the standards themselves are defective. It will be because our schools are completely dominated by the seven myths analyzed by Daisy Christodoulou. This splendid, disinfecting book needs to be distributed gratis to every teacher, administrator, and college of education professor in the U.S. It’s available at Amazon for $9.99 or for free if you have Amazon Prime.

Redux: Up, Down & Transparency: Madison Schools Received $11.8M more in State Tax Dollars last year, Local District Forecasts a Possible Reduction of $8.7M this Year; taxes up 9% a few years ago

Madison’s aid amount is about the same as it was in 2010-11. The district received a $15 million boost in aid last year mostly because 4-year-old kindergarten enrollment added about 2,000 students.

The Madison School Board taxed the maximum amount allowed last year, resulting in a 1.75 percent property tax increase. That amount was low compared to previous years because of the state aid increase. The additional funds allowed the district to spend more on building maintenance and a plan to raise low-income and minority student achievement.

Property tax increase coming