Search Results for: "Will Fitzhugh"

Global Leader Pearson Creates Leading Curriculum, Apps for Digital Learning Environments

Pearson via Will Fitzhugh: Today Pearson announced a collaboration with Microsoft Corp. that brings together the world’s leading learning company and the worldwide leader in software, services and solutions to create new applications and advance a digital education model that prepares students to thrive in an increasingly personalized learning environment. The first collaboration between the […]

What’s Holding Back American Teenagers? Our high schools are a disaster

High school, where kids socialize, show off their clothes, use their phones–and, oh yeah, go to class.

Every once in a while, education policy squeezes its way onto President Obama’s public agenda, as it did in during last month’s State of the Union address. Lately, two issues have grabbed his (and just about everyone else’s) attention: early-childhood education and access to college. But while these scholastic bookends are important, there is an awful lot of room for improvement between them. American high schools, in particular, are a disaster.

In international assessments, our elementary school students generally score toward the top of the distribution, and our middle school students usually place somewhat above the average. But our high school students score well below the international average, and they fare especially badly in math and science compared with our country’s chief economic rivals.

What’s holding back our teenagers?

One clue comes from a little-known 2003 study based on OECD data that compares the world’s 15-year-olds on two measures of student engagement: participation and “belongingness.” The measure of participation was based on how often students attended school, arrived on time, and showed up for class. The measure of belongingness was based on how much students felt they fit in to the student body, were liked by their schoolmates, and felt that they had friends in school. We might think of the first measure as an index of academic engagement and the second as a measure of social engagement.

On the measure of academic engagement, the U.S. scored only at the international average, and far lower than our chief economic rivals: China, Korea, Japan, and Germany. In these countries, students show up for school and attend their classes more reliably than almost anywhere else in the world. But on the measure of social engagement, the United States topped China, Korea, and Japan.

In America, high school is for socializing. It’s a convenient gathering place, where the really important activities are interrupted by all those annoying classes. For all but the very best American students–the ones in AP classes bound for the nation’s most selective colleges and universities–high school is tedious and unchallenging. Studies that have tracked American adolescents’ moods over the course of the day find that levels of boredom are highest during their time in school.

It’s not just No Child Left Behind or Race to the Top that has failed our adolescents–it’s every single thing we have tried.

One might be tempted to write these findings off as mere confirmation of the well-known fact that adolescents find everything boring. In fact, a huge proportion of the world’s high school students say that school is boring. But American high schools are even more boring than schools in nearly every other country, according to OECD surveys. And surveys of exchange students who have studied in America, as well as surveys of American adolescents who have studied abroad, confirm this. More than half of American high school students who have studied in another country agree that our schools are easier. Objectively, they are probably correct: American high school students spend far less time on schoolwork than their counterparts in the rest of the world.

Trends in achievement within the U.S. reveal just how bad our high schools are relative to our schools for younger students. The National Assessment of Educational Progress, administered by the U.S. Department of Education, routinely tests three age groups: 9-year-olds, 13-year-olds, and 17-year-olds. Over the past 40 years, reading scores rose by 6 percent among 9-year-olds and 3 percent among 13-year-olds. Math scores rose by 11 percent among 9-year-olds and 7 percent among 13-year-olds.

By contrast, high school students haven’t made any progress at all. Reading and math scores have remained flat among 17-year-olds, as have their scores on subject area tests in science, writing, geography, and history. And by absolute, rather than relative, standards, American high school students’ achievement is scandalous.

In other words, over the past 40 years, despite endless debates about curricula, testing, teacher training, teachers’ salaries, and performance standards, and despite billions of dollars invested in school reform, there has been no improvement–none–in the academic proficiency of American high school students.

It’s not just No Child Left Behind or Race to the Top that has failed our adolescents–it’s every single thing we have tried. The list of unsuccessful experiments is long and dispiriting. Charter high schools don’t perform any better than standard public high schools, at least with respect to student achievement. Students whose teachers “teach for America” don’t achieve any more than those whose teachers came out of conventional teacher certification programs. Once one accounts for differences in the family backgrounds of students who attend public and private high schools, there is no advantage to going to private school, either. Vouchers make no difference in student outcomes. No wonder school administrators and teachers from Atlanta to Chicago to my hometown of Philadelphia have been caught fudging data on student performance. It’s the only education strategy that consistently gets results.

The especially poor showing of high schools in America is perplexing. It has nothing to do with high schools having a more ethnically diverse population than elementary schools. In fact, elementary schools are more ethnically diverse than high schools, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Nor do high schools have more poor students. Elementary schools in America are more than twice as likely to be classified as “high-poverty” than secondary schools. Salaries are about the same for secondary and elementary school teachers. They have comparable years of education and similar years of experience. Student-teacher ratios are the same in our elementary and high schools. So are the amounts of time that students spend in the classroom. We don’t shortchange high schools financially either; American school districts actually spend a little more per capita on high school students than elementary school students.

Our high school classrooms are not understaffed, underfunded, or underutilized, by international standards. According to a 2013 OECD report, only Luxembourg, Norway, and Switzerland spend more per student. Contrary to widespread belief, American high school teachers’ salaries are comparable to those in most European and Asian countries, as are American class sizes and student-teacher ratios. And American high school students actually spend as many or more hours in the classroom each year than their counterparts in other developed countries.

This underachievement is costly: One-fifth of four-year college entrants and one-half of those entering community college need remedial education, at a cost of $3 billion each year.

The president’s call for expanding access to higher education by making college more affordable, while laudable on the face of it, is not going to solve our problem. The president and his education advisers have misdiagnosed things. The U.S. has one of the highest rates of college entry in the industrialized world. Yet it is tied for last in the rate of college completion. More than one-third of U.S. students who enter a full-time, two-year college program drop out just after one year, as do about one fifth of students who enter a four-year college. In other words, getting our adolescents to go to college isn’t the issue. It’s getting them to graduate.

If this is what we hope to accomplish, we need to rethink high school in America. It is true that providing high-quality preschool to all children is an important component of comprehensive education reform. But we can’t just do this, cross our fingers, and hope for the best. Early intervention is an investment, not an inoculation.

In recent years experts in early-child development have called for programs designed to strengthen children’s “non-cognitive” skills, pointing to research that demonstrates that later scholastic success hinges not only on conventional academic abilities but on capacities like self-control. Research on the determinants of success in adolescence and beyond has come to a similar conclusion: If we want our teenagers to thrive, we need to help them develop the non-cognitive traits it takes to complete a college degree–traits like determination, self-control, and grit. This means classes that really challenge students to work hard–something that fewer than one in six high school students report experiencing, according to Diploma to Nowhere, a 2008 report published by Strong American Schools. Unfortunately, our high schools demand so little of students that these essential capacities aren’t nurtured. As a consequence, many high school graduates, even those who have acquired the necessary academic skills to pursue college coursework, lack the wherewithal to persevere in college. Making college more affordable will not fix this problem, though we should do that too.

The good news is that advances in neuroscience are revealing adolescence to be a second period of heightened brain plasticity, not unlike the first few years of life. Even better, brain regions that are important for the development of essential non-cognitive skills are among the most malleable. And one of the most important contributors to their maturation is pushing individuals beyond their intellectual comfort zones.

It’s time for us to stop squandering this opportunity. Our kids will never rise to the challenge if the challenge doesn’t come.Laurence Steinberg is a psychology professor at Temple University and author of the forthcoming Age of Opportunity: Revelations from the New Science of Adolescence.

———————————-

“Teach with Examples”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

Monstrous (aka CC “deeper learning”)

[The Prentice Hall Common Core literature textbook for the tenth grade:]

….Teachers may (or may not) ask interested students (two, four, or half a dozen?) to read a segment of the book (presumably a brief one only describing the monster) that will lead to two silly compare-and contrast-assignments, one involving “similar novels they have read.” (Have they read any? They haven’t read Frankenstein yet.) What about the students who are not “advanced readers”? What is being done to help them become better readers? And why should even the advanced readers read only a few pages out of this classic? What should students be doing if not reading Frankenstein?

According to the notes in the margins of the Teacher’s Edition, they should begin by offering to the class “classic examples of urban myths, tales of alien abductions, or ghost stories. (Examples include stories of alligators in the sewers, a man abducted for his kidneys, and aliens landing in Roswell, New Mexico).” (The word “classic” is being used very loosely.) To reinforce the findings of this “brainstorming activity,” students should also “write a paragraph based on one of these modern urban myths.” The class will also discuss Mary Shelley’s introduction in various ways. Helping out, Elizabeth McCracken offers several more “scholar’s insights,” including one informing us of another ghost story about a man who buried his murder victim at the base of a tree “only to find that the next year’s apples all had a clot of blood at the center of them.” On the following page, we learn that Elizabeth McCracken did read the book, which she found better than the movie because, she tells us, in the book the monster can actually talk. Teachers are prompted to ask students why they think the film version would choose to keep the monster silent. Since the class will not be diverted enough with all this talk of movies, the Teacher’s Edition also recommends that talented and gifted students “illustrate one aspect of Shelley’s imaginings that is especially Gothic in its mood” and “display their Gothic art to the rest of the class.”

Do the editors realize that all this extraneous discussion of monsters and ghosts only serves to preserve the silly Halloween caricature of Frankenstein? Apparently this caricature is what they want. On page 766, students are encouraged to “write a brief autobiography of a monster.” The editors point out that monster stories are usually told from the perspective of “the humans confronting the monster.” The editors of The British Tradition want to turn the tables and have students ask themselves “what monsters think about their treatment.” Now there’s a great exercise in multiculturalism! Those poor, misunderstood monsters. Thus, students are being asked to write a monster story. What good could come from this? Without reading the novel Frankenstein itself (which does in fact tell much of the story from the monster’s perspective), students have no way of knowing how human this Gothic tale really is. After a mere three and a half pages of Mary Shelley’s introduction, the book offers a series of questions under various headings: Critical Reading, Literary Analysis, and so forth. Some of these questions are steeped in two-bit literary criticism. Others require students to delve into the moral realms of science and creation. One is a question asking students to interpret a modern cartoon about Frankenstein–funny, but out of place in this literature book. Notwithstanding whether the questions are good or bad, the enterprise is as false as the worst Hollywood versions of Frankenstein. The questions offer the façade of learning without genuine learning having taken place. That is for a very simple reason. My wife, the former English teacher who recognizes pretense when she sees it, took one look at these pages and put it very simply:

“They (the editors) are requiring students to have opinions on something they know nothing about.”

Moore, Terrence (2013-11-29).

The Story-Killers: A Common-Sense Case Against the Common Core (pp. 176-177). Kindle Edition.

————————-

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

Peach Baskets

In 1891, when Mr. James Naismith (he got his MD in 1898) put two peach baskets with the bottoms out at about 10 feet up at each end of the gymnasium in Springfield, Massachusetts, how many high school students do you think could make the three-point shot? Zero.

Today, when people see the exemplary history research papers published in The Concord Review, the most common reaction is: “These were written by High School Students?!” The reason for this disbelief is that most adults (even Edupudits, etc.) today no more expect high school student to write 11,000-word research papers than people in 1891 expected them to be able to make a three-point shot or dunk the basketball.

Theodore Sizer, late Dean of the Harvard School of Education and Headmaster of Phillips Academy, Andover, wrote, in 1988, that:

Americans shamefully underestimate their adolescents. With often misdirected generosity, we offer them all sorts of opportunities and, at least for middle-class and affluent youths, the time and resources to take advantage of them. We ask little in return. We expect little, and the young people sense this, and relax. The genially superficial is tolerated, save in areas where the high school students themselves have some control, in inter-scholastic athletics, sometimes in their part-time work, almost always in their socializing. At least if and when they reflect about it, adolescents have cause to resent us old folks. We do not signal clear standards for many important areas of their lives, and we deny them the respect of high expectations. In a word, we are careless about them, and, not surprisingly, many are thus careless about themselves. “Me take on such a difficult and responsible task?” they query, “I’m just a kid!” All sorts of young Americans are capable of solid, imaginative scholarship, and they exhibit it for us when we give them both the opportunity and a clear measure of the standard expected. Presented with this opportunity, young folk respond. The Concord Review is such an opportunity, a place for fine scholarship to be exhibited, to be exposed to that most exquisite of scholarly tests, wide publication. The Concord Review is, for the History-inclined high school student, what the best of secondary school theatre and music performances, athletics, and (in some respects) science fairs are, for their aficionados. It is a testing ground, and one of elegant style, taste and standards. The Review does not undersell students. It respects them. And in such respect is the fuel for excellence.”

Since 1987, The Concord Review has published more than a thousand 6,000-word, 8,000-word, 11,000-word, 15,000-word, and longer history papers by secondary students from 46 states and 38 other countries, and, as we only take about 5% of the ones we get, evidently several more thousands of high school students have written serious history papers and submitted them. But I was recently asked, “How many high school students do you think could actually write papers like that?”–Suggesting that it must be a very small number indeed! As small perhaps as the number of high school students who could make that three-pointer in 1891?

Some examples: Colin Rhys Hill, of Atlanta, Georgia, decided to write a 15,000-word history research paper on the Soviet-Afghan War; Sarah Willeman of Byfield, Massachusetts, decided she wanted to write a 21,000-word paper on the Mountain Meadows Massacre in Utah in 1857; Nathaniel Bernstein, of San Francisco, chose to write an 11,000-word paper on the unintended consequences of Direct Legislation reforms in the early 1900s in California; and Jonathan Lu, of Hong Kong, wrote a 13,000-word paper on the Needham Question (why did Chinese technology stall after 1500?)…(send to fitzhugh@tcr.org for pdfs of these papers).

“Where there’s a Way, there’s a Will,” I sometimes think. If peach baskets exist, some day somewhere a high school student or two will try to shoot a ball through one. Obviously by now the number of such students who can make a three-point shot is very large. We even have nationally-televised high school basketball games in which they can demonstrate such an achievement. If an international journal for the academic history research papers of secondary students exists, perhaps some students will actually write and submit them?

Most people may tell a high school students that they are not capable of doing the reading and the writing for a long serious history research paper. Most of their teachers do not want to spend the time coaching for and reading them. But my advice to any prospective high school author is (pay no attention to the people who tell you that you are only capable of writing a five-paragraph essay), and:

Prepare yourself over hours, weeks, months, and years of practice.

Make sure your feet are behind the three-point line.

Take the shot.

—————————

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

AUTODIDACT

The term “autodidact” is usually reserved for those who, like Benjamin Franklin, Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Carnegie, and so on, did not have the advantages of spending much time in school or the help of schoolteachers with their education.

I would like to suggest that every student is an autodidact, because only the student can decide what information to accept and retain. Re-education camps in the Communist world, from Korea to Vietnam to China, no doubt made claims that they could “teach” people things whether they want to learn them or not, but I would argue that the threat of force and social isolation used in such camps are not the teaching methods we are searching for in our schools.

And further, I would claim that even in re-education camps, students often indeed reserve private places in their minds about which their instructors know very little.

My main point is that the individual is the sovereign ruler of their own attention and the sole arbiter of what information they choose to admit and retain. Our system of instruction and examination has no doubt persuaded many sovereign learners over the years to accept enough of the knowledge we offer to let most of them pass whatever exams we have presented, but the cliché is that after the test, nearly all of that information is gone.

Teachers have known all this from the beginning, and so have developed and employed all their arts to first attract, and then retain, the attention of their students, and they have labored tirelessly to persuade their students that they should decide to attend to and make use of the knowledge they are offering.

One of the best arguments for having teachers be very well-grounded in the subjects they are teaching is that the likelihood increases that they will really love their subject, and it is easier for teachers to convince students of the value of what they are teaching if they clearly believe in its value themselves.

It should not be forgotten, however, that the mind is a mercurial and fickle instrument, and the attention of students is vulnerable to all the distractions of life, in the classroom and out of it. I am distressed that so many who write about education seem to overlook the role of students almost entirely, concentrating on the public policy issues of the Education Enterprise and forgetting that without the attention and interest of students, all of their efforts are futile.

It seems strange to me that so little research is ever done into the actual academic work of students, for instance whether they ever read a complete nonfiction book, and whether they every write a serious academic paper on a subject other than themselves.

For many reformers, it seems the only student work they are interested in is student scores on objective tests. Sadly, objective tests discover almost nothing about the students’ interest in their experiences of the complexity of the chemistry, history, literature, Chinese, and other subjects they have been offered.

There was a time when college entrance decisions were based on essays students would write on academic subjects, and those could reveal not only student fluency and knowledge, but something of their attachment to and appreciation for academic matter.

But now, we seem to have decided that neither we nor they have time for extended essays on history and the like (except for the International Baccalaureate, and The Concord Review), and the attractions of technology have led examiners to prefer tests that can be graded very quickly, by computer wherever possible. So, when the examiners show no interest in serious academic work, it should not surprise us that students may see less value in it as well.

The Lower Education teachers are still out there, loving their subjects, and offering them up for students to judge, and to decide how much of them they will accept into their memories and their thoughts, but meanwhile the EduPundits and the leaders of the Education Enterprise [Global Education Reform Movement = GERM, as Pasi Sahlberg calls it], with lots of funding to encourage them, sail on, ignoring the control students have, and always have had, over their own attention and their own learning.

——————————-

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

History is AWOL

The Common Core National Education Standards are, they say, very interested in having all our students taught the techniques of deeper reading, deeper writing, deeper listening, deeper analysis, and deeper thinking.

What they seen to have almost no interest in, is knowledge–for example knowledge of history, especially military history. As far as I can tell at the moment, their view of the history our high school students need to know includes: The Letter From Birmingham Jail, The Gettysburg Address, and Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address.

While these are all, of course, worthy objects for deeper reading and the like, they do not, to my mind, fully encompass the knowledge of the Magna Carta, the Constitution of the United States, the Battle of the Bulge and of Iwo Jima and of Okinawa, or the Women’s Christian Temperance Movement, or the U.S. transcontinental railroad, or the Panama Canal, or woman suffrage or the Great Depression, or a number of other interesting historical circumstances our students perhaps should know about.

Nor does it seem to call for much knowledge about William Penn, or Increase Mather, or George Washington, or Alexander Hamilton, or Robert E. Lee, or Ulysses S. Grant, or Thomas Edison, or Elizabeth Cady Stanton, or Dwight David Eisenhower, or several hundreds of other historical figures who might be not only interesting, but also important for students to be familiar with.

In short, from what I have seen, the Common Core Vision of necessary historical knowledge includes what any high school Junior ought to be able to read in one afternoon (i.e. three short “historical documents”).

Ignorance of history has, it may be said, been almost an American tradition, and many Americans have discovered in their travels, and to their embarrassment, that people in other countries may know more about our history than they do.

We have, many times in the past, even invaded countries our soldiers knew next to nothing about, and sometimes that has been a disadvantage for us. But if the Common Core doesn’t care if our students know any United States history, they are certainly not going to mind if our students don’t know the history of any other country either.

But even in schools were history is still taught, and where the Common Core has not yet sunk its roots, one area of history is perhaps neglected more than any other. Was it Trotsky who said: “You may not be interested in War, but War is interested in you.”?

And Publius Flavius Vegetius argued that: “If you want peace, prepare for war.” In many of our school history departments, military history is regarded as “militaristic,” and the thought, apparently, is that if we tell our students nothing about war, then war will simply go away.

History doesn’t seem to support that notion, and if war does come to us again, it might be useful for students in places other than our Military Academies to know something about military history. In addition, military history tells absorbing stories of some of the most inspiring efforts ever made in the history of mankind.

We talk a fair amount these days about our Wounded Warriors and about what we owe to our veterans, past and present, but for some odd reason, that seldom translates into the responsibility to teach military history, at least to some minimal extent, to the students in our public high schools.

It is quite clear to me that ignorance of history does not make history go away, and ignorance of the lessons of history does not make us better prepared to understand the issues of our time. And certainly, in spite of whatever dreams and wishes are out there, ignorance of war has not ever made, and quite probably will not make, war go away.

We want to honor our veterans, but we do not do so by erasing knowledge of our wars, past and present, from our high school history curriculum, whatever the pundits who are bringing us the Common Core may think about, and plan for, the teaching of history.

—————————

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

History Paralysis

When it comes to working together to support the survival and enjoyment of history for students in our schools, why are history teachers, as a group, as good as paralyzed?

Whatever the reason, in the national debates over nonfiction reading (history books, anyone?) and nonfiction writing for students in the schools, the voice of history teachers, at least in the wider conversation, has not been clearly heard.

Perhaps it could be because, as David Steiner, former Commissioner of Education in New York State, put it: “History is so politically toxic that no one wants to touch it.”

Have the bad feelings and fears raised over the ill-fated National History Standards which emerged from UCLA so long ago persisted and contributed to our paralysis in these national discussions?

Are we (I used to be one) too sensitive to the feelings of other members of the social studies universe? Are we too afraid that someone will say we have given insufficient space and emphasis to the sociology of the mound people of Ohio or the history and geography of the Hmong people or the psychology of the Apache and the Comanche? Or do we feel guilty, even though it is not completely our fault, that all of the Presidents of the United States have been, (so far), men?

I am concerned when the National Assessment of Educational Progress finds that 86% of our high school seniors scored Basic or Below on U.S. History, and I am appalled by stories of students, who, when asked to choose our Allies in World War II on a multiple-choice test, select Germany (both here and in the United Kingdom, I am told). After all, Germany is an ally now, they were probably an ally in World War II, right? So Presentism reaps its harvest of historical ignorance.

Of course there is always competition for time to give to subjects in schools. Various groups push their concerns all the time. Business people often argue that students should learn about the stock market at least, if not credit default swaps and the like. Other groups want other things taught. I understand that there is new energy behind the revival of home economics courses for our high school future homemakers.

But what my main efforts have been directed towards since 1987 is prevention of the need for remedial nonfiction reading and writing courses in college. My national research has found that most U.S. public high schools do not ask students to write a serious research paper, and I am convinced that, if a study were ever done, it would show that we send the vast majority of our high school graduates off without ever having assigned them a complete history book to read. Students not proficient in nonfiction reading and writing are at risk of not understanding what their professors are talking about, and are, in my view, more likely to drop out of college.

For all I know, book reports are as dead in the English departments as they are in History departments. In any case, most college professors express strong disappointment in the degree to which entering students are capable of reading the nonfiction books they are assigned and of writing the term papers that are assigned.

A study done by the Chronicle of Higher Education found that 90% of professors judge their students to be “not very well prepared” in reading, doing research, and writing.

I cannot fathom why we put off instruction in nonfiction books and term papers until college in so many cases. We start young people at a very early age in Pop Warner football and in Little League baseball, but when it comes to nonfiction reading and writing we seem content to wait until they are 18 or so.

For whatever reason, some students have not let our paralysis prevent them either from studying history or from writing serious history papers, and I have proof that they can do good work in history, if asked to do so. When I started The Concord Review in 1987, I hoped that students might send me 4,000-word research papers in history. By now, I have published, in 98 issues, 1,077 history research papers averaging 6,000 words, on a huge variety of topics, by high school students from 46 states and 38 other countries.

Some have been inspired by their history teachers, other by their history-buff parents, but a good number have been encouraged by seeing the exemplary work of their peers in print. Here are parts of two comments from authors–Kaitlin Marie Bergan: “When I first came across The Concord Review, I was extremely impressed by the quality of writing and the breadth of historical topics covered by the essays in it. While most of the writing I have completed for my high school history classes has been formulaic and limited to specified topics, The Concord Review motivated me to undertake independent research in the development of the American Economy. The chance to delve further into a historical topic was an incredible experience for me and the honor of being published is by far the greatest I have ever received. This coming autumn, I will be starting at Oxford University, where I will be concentrating in Modern History.” And Emma Curran Donnelly Hulse: “As I began to research the Ladies’ Land League, I looked to The Concord Review for guidance on how to approach my task. At first, I did check out every relevant book from the library, running up some impressive fines in the process, but I learned to skim bibliographies and academic databases to find more interesting texts. I read about women’s history, agrarian activism and Irish nationalism, considering the ideas of feminist and radical historians alongside contemporary accounts…Writing about the Ladies’ Land League, I finally understood and appreciated the beautiful complexity of history…In short, I would like to thank you not only for publishing my essay, but for motivating me to develop a deeper understanding of history. I hope that The Concord Review will continue to fascinate, challenge and inspire young historians for years to come.”

Lots of high school [and middle school] students are sitting out there, waiting to be inspired by their history teachers [and their peers] to read history books and to prepare their best history research papers, and lots of history teachers are out there, wishing there were a stronger and more optimistic set of arguments coming from a history presence in the national conversation about higher standards for nonfiction reading and writing in our schools.

—————————–

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

Missing out on timeless literature

He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice,” Mississippi’s William Faulkner said of man upon receiving the 1949 Nobel Prize in Literature, “but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things.”

New Englanders can rightfully claim to have been America’s 19th-century literary hub, but no other regional landscape dominated 20th-century literature like the South and its genius for storytelling. Famously, Faulkner’s imaginary Yoknapatawpha County, Chickasaw for “split land,” provided the setting for his most inspired novels.

American high school students should read Southern writers like Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Flannery O’Connor and Walker Percy, author of the 1962 National Book Award-winning “The Moviegoer.” Percy crafted stories about “the dislocation of man in the modern age,” while contributing to a “community of discourse” around fiction writing. His Greenville, Miss., was a wellspring of outstanding writers.

Greenville’s patriarch, William Alexander Percy, was a lawyer, planter and poet from a suicide-plagued family. He authored the best-selling 1941 memoir “Lanterns on the Levee.” His second cousin, Walker Percy, and Walker’s lifelong best friend, Shelby Foote, were both young when they lost their fathers. Will Percy’s book-filled house became a sanctuary for writers, journalists and musicians, as the man himself mentored a region.

2 Hours Per Week for Homework, but 8 ½ per day Stabbing Girls and Other Media Fun.

Bill Korach, via Will Fitzhugh:

A new video war game “Call of Duty” integrates women as the objects of violence while time spent on homework declines to about two hours per week. This is not a formula designed to produce an educated literate society that will be competitive in the global economy. On the other hand, spending 8 ½ hours per day on media including games of shocking violence is a formula that will continue to coarsen our culture and even produce real violence. Recall that the Columbine killers were avid video game players.

The Kaiser Foundation reported in January 2010, that:

“Over the past five years, there has been a huge increase in media use among young people. Five years ago, we reported that young people spent an average of nearly 61/2 hours (6:21) a day with media–and managed to pack more than 81/2 hours (8:33) worth of media content into that time by multitasking. At that point it seemed that young people’s lives were filled to the bursting point with media. Today, however, those levels of use have been shattered. Over the past five years, young people have increased the amount of time they spend consuming media by an hour and seventeen minutes daily, from 6:21 to 7:38–almost the amount of time most adults spend at work each day, except that young people use media seven days a week instead of five. [53 hours a week]”

Leftist Educator Diane Ravitch Meets Her Match: An Important Critique by Sol Stern

Do you know who Diane Ravitch is? If not, you should. No other educator has been acclaimed in so many places as the woman who can lead American education into the future. Her new book, Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America’s Public Schools, had a first printing of 75,000 copies and quickly made the New York Times non-fiction best seller list.

Recently, the leading magazine for left-liberal intellectuals, The New York Review of Books, featured a cover story about Ravitch by Andrew Delbanco. He compares the approaches of the educator most despised by the Left, Michelle Rhee, with Ravitch. He calls Ravitch “our leading historian of primary and secondary education.” Having established that, he goes on to note Ravitch’s condemnation of Rhee, which he says “borders on contempt.” Delbanco also dislikes Rhee. He does not agree with what he calls her “determination to remake public institutions on the model of private corporations.” Rhee is pro-corporate, a woman who wants “to introduce private competition (in police, military, and postal services, for example) where government was once the only provider.” In other words, Rhee stands with the enemies of the Left who want school choice for poor children, vouchers, charter schools, and competition, rather than more pay for teachers, smaller classes, and working with and through the teachers’ unions.

Send in the SEALs: Can a new generation of young, Navy SEAL-like teachers finally club the achievement gap out of existence?

EduShyster

Hedge funder Whitney Tilson argues that a new generation of young Navy SEAL-like teachers can club the achievement gap out of existence.

Can a new generation of young, Navy SEAL-like teachers finally club the achievement gap out of existence? That is today’s fiercely urgent question, reader, and believe it or not, I do not ask it in jest. The call to send in the SEALs comes from hedge fund manager and edu-visionary extraordinaire Whitney Tilson. When Tilson read this recent New York Times story about high turnover among young charter school teachers, he went ballistic, to use a military metaphor. After all, turnover among Navy SEALs is also very high, notes Tilson, and no one complains about that.

Bigger rigor

So how exactly is the young super teacher in an urban No Excuses charter school like a Navy SEAL? Better yet, how are such teachers NOT like SEALs? Both sign onto an all-consuming mission, the SEAL to take on any situation or enemy the world has to offer, the teacher to tackle the greatest enemy our nation has ever known: teacher union low expectations. But as Tilson has seen second-hand, being a “bad a**” warrior is exhausting, which is why SEALs, like young super teachers, enjoy extraordinarily short careers.

But the work is incredibly intense and not really compatible with family life, so few are doing active missions for their career–they move on into management/leadership positions or go into the private sector (egads!). Could you imagine the NY Times writing a snarky story about high turnover among SEALs?!

Cream of the crop

Egads! indeed, reader. In fact, now that I think of it, *crushing* the achievement gap in our failed and failing public schools is almost exactly like delivering highly specialized, intensely challenging warfare capabilities that are beyond the means of standard military forces. For one thing, the SEALs are extremely choosy about who they let into their ranks, just as we’ll need to be if we’re going to replace our old, low-expectations teachers with fresh young commandos. Only the cream of the crop make it to SEALdom, and by cream, I mean “cream” colored. The SEALs are overwhelmingly white; just 2% of SEAL officers are African American.

See the world

And let’s not forget that SEALs and new urban teachers both get plenty of opportunities to experience parts of the world they haven’t seen before. The elite Navy men train and operate in desert and urban areas, mountains and woodlands, and jungle and arctic conditions, while members of the elite teaching force spend two years combating the achievement gap in the urban schools before they receive officer status. And while Frog Men live on military bases, our commando teachers increasingly live in special encampments built just for them.

And here is where our metaphor begins to break down ever so slightly….

Of course, there are a few teeny tiny areas where the SEALs differ from the young teachers who will finally club the achievement gap out of existence. There is, for instance, the teeny tiny matter of the training that the SEALs receive: 8-weeks Naval Special Warfare Prep School, 24-weeks Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/s) Training, 3-weeks Parachute Jump School, 26-weeks SEAL Qualification Training (SQT), followed by 18-months of pre-deployment training, including 6-month Individual Specialty Training, 6-month Unit Level Training and 6-month Task Group Level Training before they are considered deployable. TFA, which Tilson praises for its “yeoman” work in recruiting and grooming the next generation of urban teacher hot shots, relies upon an, ahem, somewhat different approach…

Send tips and comments to tips@edushyster.com.

——————————

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

Distraction

Let’s say the history teacher, a descendant of the 1960s, is talking (of course) about the Vietnam War, and how Walter Cronkite won the Tet Offensive, even though the North lost it, and the student is perhaps paying some attention, but when the teacher shifts to an explanation of the hardships of war in the hot weather and the humidity, the student, effortlessly, may begin to remember what his grandfather told him about the cold at the Chosin Reservoir in 1950, and how easy it was to get frostbitten or even to freeze to death.

The teacher, quite understandably, so often has no idea that the student is no longer listening to, or learning from him, no matter how “great” the teacher is.

Those who say that teacher quality is the most important variable in student academic achievement seem to have forgotten the student’s role in student academic achievement. They have failed to think about, and they have not come to realize, the fact that the student is the sole proprietor of his/her own attention, and that her/his attention is the sine qua non for student academic achievement.

Again, the history teacher might be talking about the rise of organized labor in American life, and the student’s mind could easily slip away to the stories her aunt has told her about the difficult labor she had to go through with her first daughter.

Attention wanders, and in class wandering attention means the end of learning on the current topic for the time being, at least for that student, and for the “education” planned for that class period for any and all distracted students.

What can be done about this wayward-attention phenomenon? We might start by realizing that students own their attention and that we must negotiate with them successfully if we are to convince them to bring that attention to our offerings and to their duties as students. (Doesn’t that sound quaint?–Students have duties?)

With this in mind, we might spend more time explaining why what we are teaching in a given period on any given day is worth the attention we need from students. We can order them to pay attention (that doesn’t work), but we might be able to sell them on the chance that if they give their attention to what we are offering, it might prove to be worth their while.

We won’t sell the opportunity to every one, but some students might be grateful for the respect we pay to their ownership of their own minds and their own attention, and more of them might be willing to give us the benefit of the doubt and give our

presentations and plans their attention on a trial basis. (And some students will surely be influenced by the attention they see their peers giving to the work at hand…)

Then, if what we are teaching is as important and as interesting to us as we hope it will be to them, there is a chance (well-tested in experience) that they may indeed find it of interest to them as well, and they will be, in that subject perhaps, on their way to becoming educated, and more than that even, they might be on their way to deciding to teach themselves more about the subject as well. Thus are scholars born.

————————-

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

www.tcr.org/blog

National Civics, History Tests to Disappear

The National Assessment of Educational Progress exams in civics, U.S. history, and geography have been indefinitely postponed for fourth and twelfth graders. The Obama administration says this is due to a $6.8 million sequestration budget cut. The three exams will be replaced by a single, new test: Technology and Engineering Literacy.

“Without these tests, advocates for a richer civic education will not have any kind of test to use as leverage to get more civic education in the classrooms,” said John Hale, associate director at the Center for Civic Education.

NAEP is a set of national tests of fourth, eighth, and twelfth graders that track achievement on various subjects over time. Researchers collect data for state to state comparisons in mathematics, reading, science, and writing. The other subjects only provide national statistics and are administered to fewer students. The tests provide basic information about students but do not automatically trigger consequences for teachers, students, and schools.

Students have historically performed extremely poorly on these three tests. In 2010, the last administration of the history test, students performed worse on it than on any other NAEP test. That year, less than half of eighth-graders knew the purpose of the Bill of Rights, and only 1 in 10 could pick a definition of the system of checks and balance on the civics exam.

Science vs. Humanities

Since most civic education is taught to first-semester high school seniors, Hale said, not testing in twelfth grade creates a major gap of information.

“Is it possible to have a responsible citizenry if we don’t teach them civics, history, and the humanities?” said Gary Nash, a professor of history education (sic) at the University of California Los Angeles. Postponing the exams, typically administered every four years, does not mean classroom education in the humanities will be cut. But the cuts indirectly say we can do without civics and U.S. history, Nash said.

Trading the humanities tests for technology tests is necessary to measure “the competitiveness of U.S. students in a science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)-focused world,” said David Driscoll, chair of the NAEP Governing Board, in a statement. “The [Technology and Engineering Literacy] assessment, along with the existing NAEP science and mathematics assessments, will help the nation know if we are making progress in the areas of STEM education.”

Nash agrees the U.S. needs more engineers and scientists: “But what are they without humanities under their belt?” he said.

Excellence in one area flows into others

A summer report from the Commission on the Humanities and Social Sciences explained the need for these subjects this way: “The humanities and social sciences provide an intellectual framework and context for understanding and thriving in a changing world. When we study these subjects, we learn not only what but how and why.”

Nash pointed out that Franklin High School in the Los Angeles Unified School district is 94 percent Latino, and many families are immigrants. Without changing anything in science and math, the school began to emphasize humanities. The scores in science and math improved, testing almost on par with students in Beverly Hills. “It’s about increasing their passion for learning,” he says. Furthermore, giving students a context for learning helps them learn more.

Masters of Our Government

Students must be prepared “to think for themselves as independent citizens,” said Hale. “Civics and Government (& History) is (are) as generative as math; we are not born as great democratic citizens. We aren’t born knowing why everyone should have the right to political speech, even if it is intolerant speech.”

Consider the current events of the last few weeks, he said: the Supreme Court rulings on marriage and the Voting Rights Act, the National Security Administration’s data collection, and Congress debating immigration and student loan rates.

“Our leaders make decisions every day based on interpretations on the proper role of government; we have no way of knowing if these [decisions] are good or bad,” Hale continued. “We are supposed to be masters of our government, not servants of it.”

Cutting the civics tests indicates the government’s priorities, and priorities affect curriculum, Nash noted. He suggested danger for a country that must govern itself if children do not learn how.—————————–

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

www.tcr.org/blog

On Serious Secondary School Scholarship

I’ve often said that all NAIS schools are “college-prep,” even the early childhood schools like The Children’s School (Connecticut) [age 2 through eighth grade], and the learning differences (LD) schools like Lawrence School (Ohio) [grades K – 12], and scores of other independent schools like them across the country. They, like their more traditional cousins in our membership, are college-prep because parents choose them with college in mind, believing, rightfully, that an independent school with a mission that matches their child’s needs and proclivities will be the surest path to success in secondary school and college. And all of our schools deliver on that expectation.

I’ve also often said that the early childhood programs in NAIS schools and our LD schools (or the LD “schools within a school” in the traditional school model) are often the most innovative, often the first to adopt the new thinking, the new technologies, and the new research (especially on brain-based learning and differentiated instruction). That said, we are collectively, in the independent school world, on the cusp of significant re-engineering of schools, and what it means to be an outstanding place to learn. This is exemplified by Grant Lichtman’s blogs on his journey across America to discover where innovation is sprouting up in independent schools. No better time, no better place for every independent school leader and teacher to think about where, and how, we will innovate at each of our schools.

While “Change is inevitable, growth optional” (John C. Maxwell), I’d like to note that a rapidly changing landscape does not mean that everything old should be subject to change. For me, character first is the defining quality that makes independent schools strong. The founders of the first independent schools in America knew that, as do the founders of our newest schools. For example, the constitutions of both Phillips Academy (Massachusetts) and Phillips Exeter Academy (New Hampshire) include a charge to the masters (teachers) exhorting them to attend to the character of their wards: “[T]hough goodness without knowledge (as it respects others) is weak and feeble; yet knowledge without goodness is dangerous; and that both united form the noblest character, and lay the surest foundation of usefulness to mankind.”1 Have truer words ever been spoken? Or clearer insight into what makes great schools and successful (“good and smart”) graduates?

So, character first. And the adults are the moral mentors and models. But for college-prep schools, a second maxim should be “academics second,” meaning what one might call “serious scholarship.” While the means of conducting serious scholarship (video oral histories, crowd-sourcing, data mining via the Internet, etc.) are indeed changing, I like the case made by Will Fitzhugh, editor of The Concord Review, that serious scholarship in the form of a substantial publication-worthy research paper is the entry ticket for future academic success (and selective college admissions).

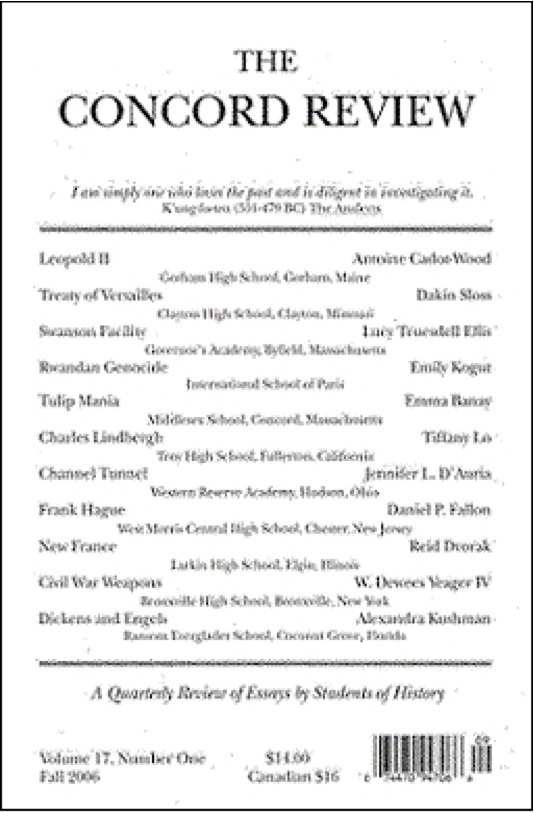

The Concord Review, launched by Fitzhugh in 1987, is an excellent periodical of secondary school research in the subject of history. As Fitzhugh is fond of pointing out, The Concord Review is more “selective” than Princeton: one out of 20 submissions to the Review published vs. one out of 19 applicants to Princeton admitted. And the requirements of the paper would be daunting to all but the most ambitious student (typically 4,000 – 6,000 words, but sometimes much longer, 10,000 words or more).2 A quick scan of the research paper titles from the most recent issue of the Review reveals both the most esoteric and fascinating of subjects chosen by these young scholars.

I recommend that all teachers read (and perhaps weep about) any student essay from past Concord Review papers archived on the magazine’s website to find out what serious scholarship at the secondary school level looks, and sounds, like. (In fact, from what my college president colleagues tell me, much college student writing today wouldn’t have a chance of publication in The Concord Review.)

New Science Standards Put Global Warming at Core of Curriculum

One doesn’t need to be a global-warming skeptic to be appalled by a new set of national K-12 science standards. Those standards, developed by educrats and science administrators, and likely to be adopted initially by up to two dozen states, put the study of global warming and other ways that humans are destroying life as we know it at the very core of science education. This is a political choice, not a scientific one. But the standards are equally troubling in their embrace of the nostrums of progressive pedagogy.

Students educated under the Next Generation Science Standards will begin their lifelong attention to climate change as soon as they enter school. Kindergartners will be expected to “use tools and materials to design and build a structure that will reduce the warming effect of sunlight on an area” (perhaps this is what used to be known as “building a fort”) and “develop understanding of patterns and variations in local weather and the purpose of weather forecasting to prepare for, and respond to, severe weather.” Things get even scarier by the third grade, when students should be asking such questions as: “How can the impact of weather-related hazards be reduced?” The standards don’t mention protesting the Keystone pipeline as a possible “real-world” answer to the question of how to reduce “weather-related hazards,” but rest assured that the graduates of America’s left-wing education schools will not hesitate to include such hands-on learning experiences in their global-warming-politics–oops, make that “science”–classes. By high school, students are squarely in the world of environmental policy-making, expected to “evaluate a solution to a complex real-world problem based on prioritized criteria and trade-offs that account for a range of constraints, including cost, safety, reliability, and aesthetics, as well as possible social, cultural, and environmental impacts.”

Hard as it may be for the groups such the Alliance for Climate Education, a purveyor of climate-change school programs and–surprise!–an enthusiastic backer of the new standards, there really are other important areas of knowledge and concern. As long as we’re picking and choosing among scientific problems, why not start kindergartners thinking about cell mutation or neural pathways so they can fight cancer and Alzheimer’s disease when they grow up?

But even without their preening obsession with climate, biodiversity, and sustainability, the standards are a recipe for further American knowledge decline. The New York Times reports that the standards’ authors anticipate the possible elimination of traditional classes such as biology and chemistry from high school in favor of a more “holistic” approach. This contempt for traditional disciplines has already polluted college education, but it could do far more damage in high school. The disciplines represent real bodies of knowledge that must be mastered before one can begin to be legitimately interdisciplinary.

The standards drearily mimic progressive education’s enthusiasm for “critical-thinking skills.” Fourth-graders sound like veritable geysers of high-level abstract reasoning, expected to “demonstrate grade-appropriate proficiency in asking questions, developing and using models, planning and carrying out investigations, analyzing and interpreting data, constructing explanations and designing solutions, engaging in argument from evidence, and obtaining, evaluating, and communicating information.” I’d be happy if they knew all the planets, continents, major oceans and rivers, and a few galaxies. Such fancy-ancy cognitive talk gives teachers an excuse to gloss over the hard work of knocking concrete facts into their students’ heads–and ignores the truth that mastering such facts can be a source of pleasure and pride.

Chinese students are not flooding into American Ph.D. programs because they have spent their high-school years pondering “a technological solution that reduces impacts of human activities on natural systems,” as the standards propose. They are filling the slots that Americans are unqualified for because they have spent years memorizing the Krebs cycle, the process of meiosis and mitosis, the periodic table, and the laws of thermodynamics and motion. The new science standards guarantee that we will look back on the years when Americans made up a piddling 50 percent of graduate-level science students as the high-water mark of American scientific literacy.—————————–

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

www.tcr.org/blog

“Uncommonly Bad” (excerpt)

Jane Robbins – National Association of Scholars Academic Questions, Spring 2013, Volume 26, Number 1

The advent of the Common Core State Standards has prompted a new discussion

about how to produce students who are “college- and career-ready.” But this question differs from the one that governed education throughout most of our history. We used to ask, what should a student know to become an educated citizen? Education would prepare one for college or career, certainly, but, more broadly, for life. What vision of education are we now advancing? As with parents and state legislators, academia has been largely excluded from this discussion…

…Should students read entire books? This is generally unnecessary, apparently, to get the flavor of the work and to have something to think critically about. Will Fitzhugh of The Concord Review notes this truncating feature of Common Core:“Let us consider saving students more time from their fictional non-informational text readings (previously known as literature) by cutting back on the complete novels, plays and poems formerly offered in our high schools. For instance, instead of Pride and Prejudice (the whole novel), students could be asked to read Chapter Three. Instead of the complete Romeo and Juliet, they could read Act Two, Scene Two, and in poetry, instead of a whole sonnet, perhaps just alternate stanzas could be assigned. In this way, they could get the ‘gist’ of great works of literature, enough to be, as it were, ‘grist’ for their deeper analytic cognitive thinking skill mills.”39

A member of the “Implementing Common Core Standards” team at the Center for Teaching Quality argues that excerpts can be as educational as complete works:

“Not every student needs to read every word of every work. We can pull essential excerpts and examine them in small chunks–words, phrases, sentences–asking students to wrestle meaning from the text.”40

It is unclear how students can “wrestle meaning” from “words” or “phrases” wrenched cleanly from their context.=============

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

www.tcr.org/blog

Bend it Like Truman

In the United Kingdom the number of reports of the verbal and physical abuse of teachers is growing at a sad and steady rate. In the United States as well, a number of fine teachers say that they are leaving the profession primarily because of the out-of-control attitudes and behavior of poorly-raised children who will not take any responsibility for their own education and don’t seem to mind if they ruin the educational chances of their peers.

David McCullough tells us that when Harry Truman took over the artillery outfit, Battery ‘D’, “the new captain said nothing for what seemed the longest time. He just stood looking everybody over, up and down the line slowly, several times. Because of their previous (mis) conduct, the men were expecting a tongue lashing. Captain Truman only studied them…At last he called ‘Dismissed!’ As he turned and walked away, the men gave him a Bronx cheer….In the morning Captain Truman posted the names of the noncommissioned officers who were ‘busted’ in rank…the First Sergeant was at the head of the list…Harry called in the other noncommissioned officers and told them it was up to them to straighten things out. ‘I didn’t come here to get along with you,’ he said. ‘You’ve got to get along with me. And if there are any of you who can’t, speak up right now, and I’ll bust you back right now.”

Now, I do realize the classroom is not a military unit, and that students cannot be busted back to a previous grade, however their behavior suggests that they don’t belong in a higher grade. But Truman realized poor discipline would endanger the lives of the men in his unit, and teachers, however much they yearn to be liked, relevant, and even loved, need to realize and accept that poor discipline in their classes will destroy some of the educational opportunities of their students. As it turned out, his unit respected and loved Truman in time, and lined Pennsylvania avenue for his inauguration parade.

For years, the Old Battleaxe was offered as a stereotype of the stern, demanding teacher who represented the expectations of the wider community in the classroom and required students to meet her standards.

In The Lowering of Higher Education, Jackson Toby quotes the experience of one man with an Old Battleaxe:

“Professor Emeritus of Religion at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota, Walter Benjamin, wrote about a demanding freshman English teacher, Dr. Doris Garey, whose course he had taken in 1946, in an article entitled ‘When an ‘A’ Meant Something.’ Professor Benjamin praised the memory of Dr. Garey and expressed gratitude for what her demanding standards had taught him.

‘Even though she had a bachelor’s degree from Mount Holyoke and a doctorate from Wisconsin, Miss Garey was the low person in the department pecking order. And physically she was a lightweight–she could not have stood more than 4-foot-10 or weighed more than 100 pounds. But she had the pedagogical mass of a Sumo wrestler. Her literary expectations were stratospheric; she was the academic equivalent of my [Marine] boot camp drill instructor…The showboats (other instructors) had long since faded, along with their banter, jokes and easy grades. It was the no-nonsense Miss Garey whose memory endured.'”

In my view, too many of our teachers have been seduced by the ideas that they should be making sure their students have fun, and that their teaching should include “relevant” material from the evanescent present of her students, their egregiously temporary pop culture, and from current events of passing interest.

Once discipline and student responsibility for their own learning is established and understood, there can be a lot of interesting and even entertaining times in the classroom. Without them, classes are in a world of trouble. Samuel Gompers used to read aloud for their enjoyment to a room full of employees making cigars, but they continued to make the cigars while he did it.

In education reform discussions in general, in my view practically all the attention is on what the adults are and/or should be doing, and almost no attention is given to what students are and should be doing. Leaving them out of the equation quite naturally contributes to poor discipline and reduced learning.

A suburban high school English teacher in Pennsylvania wrote that: “My students are out of control,” Munroe, who has taught 10th, 11th and 12th grades, wrote in one post. “They are rude, disengaged, lazy whiners. They curse, discuss drugs, talk back, argue for grades, complain about everything, fancy themselves entitled to whatever they desire, and are just generally annoying.” And one of her students commented: “As far as motivated high school students, she’s completely correct. High school kids don’t want to do anything…It’s a teacher’s job, however, to give students the motivation to learn.”

As long as too many of us think education is the teacher’s responsibility alone, we will have failed to understand what the job of learning requires of students, and we will be unable to make sense of the outcomes of our huge investments in education.

————————-

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

www.tcr.org/blog

It’s the Students, Stupid

The billionaires’ club, with their long retinue of pundits, researchers, and other hangers-on, are giving their attention, some of the time, to education. But they are not paying attention to the academic work of students, or to their responsibility for their own education.

Mr. Gates spent nearly two hundred million dollars recently on a program for teacher assessment, but does he realize that in almost every class there are students as well, and that they have a lot to say about what the teacher can accomplish?

One pundit came to speak in Boston. When told that lots of good teachers were being driven out of the profession by the absence of discipline among students, he said, “They need better classroom management skills.” I don’t think he had ever “managed” a classroom, but I told him this story:

When Theodore Roosevelt was President, he had a guest one day in the oval office, and his daughter Alice came roaring through the room disturbing everything. The guest said, “Can’t you control Alice?” And Roosevelt said, “I can be President of the United States, or I can control Alice, but not both.”

Lots and lots of teachers have students in their classes who have not been taught by KIPP, to “Work Hard, Be Nice.” Their inability to control themselves and behave with courtesy and respect for their teacher and their fellow students frequently degrades and can even disintegrate the academic integrity of the class, which damages not only their own chance to learn, but prevents all their classmates from learning as well.

In 2004, Paul A. Zoch, a teacher from Texas, wrote in Doomed to Fail (p. 150) that: “Let there be no doubt about it: the United States looks to its teachers and their efforts, but not to its students and their efforts, for success in education.” Nine years later that remains the problem with the Edupundits and their funders.

Of course, one problem for the edureformers is that you can fire teachers but you can’t fire students. If students fail, largely through their own poor attendance, inattention and destructive behavior in class, we can’t blame them. Only the teachers can be held to account. This is beyond stupid, verging on willful blindness.

The University of Indiana, in its most recent Survey of High School Student Engagement, interviewed 143,052 U.S. high school students and found that 42.5% of them spend an hour or less each week on homework and 82.7% spend five hours or less each week on their homework. The average Korean student spends fifteen hours a week on homework, and that does not include evening hagwon sessions of two or three hours. Can anyone see a difference here? And, by the way, American students spend 53 hours a week playing video games and using other sorts of electronic entertainment.

Will Fitzhugh, The Concord Review

While they play, and consume expensive products of the technology companies, students in other countries are studying hard, behaving in class, and taking their educational opportunities seriously so they can eat our lunch, which they are starting to do.

But let’s blame the teachers in the United States and ignore what their students are doing, in class and after class. That will work, won’t it?

Of course what teachers and all the other employees of our school systems do is important. But ignoring students and their work, and blaming teachers for poor student academic performance, would be like blaming a trainer if his boxer gets knocked out in the ring, while not noticing that the boxer stands in front of his opponent with his hands at his sides all the time.

We need high academic achievement, but we will not get it by blaming teachers and driving them out of the profession, while not noticing that students have an important, and even crucial, responsibility for their own learning.

Ignoring the role of our students in their own education, which at the “highest” levels of funded programs we do, is not only dumb, it will virtually consign all the other efforts to failure. Think about it.

The billionaires’ club, with their long retinue of pundits, researchers, and other hangers-on, are giving their attention, some of the time, to education. But they are not paying attention to the academic work of students, or to their responsibility for their own education.

Mr. Gates spent nearly two hundred million dollars recently on a program for teacher assessment, but does he realize that in almost every class there are students as well, and that they have a lot to say about what the teacher can accomplish?

One pundit came to speak in Boston. When told that lots of good teachers were being driven out of the profession by the absence of discipline among students, he said, “They need better classroom management skills.” I don’t think he had ever “managed” a classroom, but I told him this story:

When Theodore Roosevelt was President, he had a guest one day in the oval office, and his daughter Alice came roaring through the room disturbing everything. The guest said, “Can’t you control Alice?” And Roosevelt said, “I can be President of the United States, or I can control Alice, but not both.”

Lots and lots of teachers have students in their classes who have not been taught by KIPP, to “Work Hard, Be Nice.” Their inability to control themselves and behave with courtesy and respect for their teacher and their fellow students frequently degrades and can even disintegrate the academic integrity of the class, which damages not only their own chance to learn, but prevents all their classmates from learning as well.

In 2004, Paul A. Zoch, a teacher from Texas, wrote in Doomed to Fail (p. 150) that: “Let there be no doubt about it: the United States looks to its teachers and their efforts, but not to its students and their efforts, for success in education.” Nine years later that remains the problem with the Edupundits and their funders.

Of course, one problem for the edureformers is that you can fire teachers but you can’t fire students. If students fail, largely through their own poor attendance, inattention and destructive behavior in class, we can’t blame them. Only the teachers can be held to account. This is beyond stupid, verging on willful blindness.

The University of Indiana, in its most recent Survey of High School Student Engagement, interviewed 143,052 U.S. high school students and found that 42.5% of them spend an hour or less each week on homework and 82.7% spend five hours or less each week on their homework. The average Korean student spends fifteen hours a week on homework, and that does not include evening hagwon sessions of two or three hours. Can anyone see a difference here? And, by the way, American students spend 53 hours a week playing video games and using other sorts of electronic entertainment.

While they play, and consume expensive products of the technology companies, students in other countries are studying hard, behaving in class, and taking their educational opportunities seriously so they can eat our lunch, which they are starting to do.

But let’s blame the teachers in the United States and ignore what their students are doing, in class and after class. That will work, won’t it?

Of course what teachers and all the other employees of our school systems do is important. But ignoring students and their work, and blaming teachers for poor student academic performance, would be like blaming a trainer if his boxer gets knocked out in the ring, while not noticing that the boxer stands in front of his opponent with his hands at his sides all the time.

We need high academic achievement, but we will not get it by blaming teachers and driving them out of the profession, while not noticing that students have an important, and even crucial, responsibility for their own learning.

Ignoring the role of our students in their own education, which at the “highest” levels of funded programs we do, is not only dumb, it will virtually consign all the other efforts to failure. Think about it.

Will Fitzhugh

The Concord Review