Search Results for: Behavior education plan

Wisconsin DPI Superintendent Tony Evers Responds to Madison Teachers’ Questions

Tony Evers (PDF): 1. Why are you running for State Superintendent of Public Instruction? I’ve been an educator all my adult life. I grew up in small town Plymouth, WI. Worked at a canning factory in high school, put myself through college, and married my kindergarten sweetheart, Kathy-also a teacher. I taught and became a […]

“Why Johnny can’t write”

Heather Mac Donald: American employers regard the nation’s educational system as an irrelevance, according to a Census Bureau survey released in February of this year. Businesses ignore a prospective employee’s educational credentials in favor of his work history and attitude. Although the census researchers did not venture any hypothesis for this strange behavior, anyone familiar […]

Madison Schools Share Data with Forward Madison

Agreement (PDF): The data listed below will be made available to Forward Madison researchers upon request. There are two types of data potentially needed – individual-level data and aggregate by school. Individual, student-level data Student demographics, including: o Student ID # Race/ethnicity Special Education services required o ELL status Advanced learner status Student academic and […]

With Viral “Rip & Redo” Video, Both The NYT & Success Academy Could Have Done Better

Alexander Russo: On Friday morning, this shocking video was published in the Metro Section of the New York Times. On a surreptitious cell phone video, Success Academy Charter Schools (SA) Charlotte Dial berates a student. If you haven’t already stopped to watch it, you should do so now. It’s only about a minute long. (No […]

Teaching Machines and Turing Machines: The History of the Future of Labor and Learning; Stuck In The Past

Audrey Waters: In 1913, Thomas Edison predicted that “Books will soon be obsolete in schools.” He wasn’t the only person at the time imagining how emergent technologies might change education. Columbia University educational psychology professor Edward Thorndike – behaviorist and creator of the multiple choice test – also imagined “what if” printed books would be […]

Madison Needs To Remove The Blinders

Mitch Henck: Gee, Kaleem Caire and other black community leaders fought for Madison Prep. It was a proposed charter school aimed at serving young males, mostly black and Hispanic, to be taught predominantly by teachers of color for more effective role modeling. Berg and several white conservatives in Madison, along with moderate John Roach, supported […]

“The Plight of History in American Schools”

Diane Ravitch writing in Educational Excellence Network, 1989: Futuristic novels with a bleak vision of the prospects for the free individual characteristically portray a society in which the dictatorship has eliminated or strictly controls knowledge of the past. In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, the regime successfully wages a “campaign against the Past” by banning […]

With big data invading campus, universities risk unfairly profiling their students

Evan Selinger: Privacy advocates have long been pushing for laws governing how schools and companies treat data gathered from students using technology in the classroom. Most now applaud President Obama’s newly announced Student Digital Privacy Act to ensure “data collected in the educational context is used only for educational purposes.” But while young students are […]

Madison Schools’ 2014-2015 Budget a No No for Governor Candidate Burke

Chris Rickert: It’s no surprise Democratic nominee for governor and Madison School Board member Mary Burke isn’t saying how she plans to vote Monday on a proposed school district budget that includes a $100 tax increase for the average homeowner. For purely political reasons, dropping that particular dime would be a pretty dumb thing to […]

Election Grist: Madison Teachers Inc. has been a bad corporate citizen for too long

David Blaska: Teachers are some of our most dedicated public servants. Many inspiring educators have changed lives for the better in Madison’s public schools. But their union is a horror. Madison Teachers Inc. has been a bad corporate citizen for decades. Selfish, arrogant, and bullying, it has fostered an angry, us-versus-them hostility toward parents, taxpayers, […]

Commentary on Madison’s Long Term Achievement Gap Challenges; Single Year Data Points…

Pat Schneider: “It seems reasonable to attribute a good share of the improvements to the specific and focused strategies we have pursued this year,” Hughes writes. The process of improvement will become self-reinforcing, he predicts. “This bodes well for better results on the horizon.” Not so fast, writes Madison attorney Jeff Spitzer-Resnick in his Systems […]

2013 Madison Summer School Report

The district provided a comprehensive extended learning summer school program, K-Ready through 12th grade, at ten sites and served 5,097 students. At each of the K-8 sites, there was direction by a principal, professional Leopold, Chavez, Black Hawk and Toki, and oral language development was offered at Blackhawk and Toki. The 4th grade promotion classes were held at each elementary school, and 8th grade promotion classes were held at the two middle school sites.

Students in grades K-2 who received a 1 or 2 on their report card in literacy, and students in grades 3-5 who received a 1 or 2 in math or literacy, were invited to attend SLA. The 6-7 grade students who received a GPA of 2.0 or lower, or a 1 or 2 on WKCE, were invited to attend SLA. As in 2012, students with report cards indicating behavioral concerns were invited to attend summer school. Additionally, the summer school criterion for grades 5K-7th included consideration for students receiving a 3 or 4 asterisk grade on their report card (an asterisk grade indicates the student receives modified curriculum). In total, the academic program served 2,910 students, ranging from those entering five-year-old kindergarten through 8th grade.

High school courses were offered for credit recovery, first-time credit, and electives including English/language arts, math, science, social studies, health, physical education, keyboarding, computer literacy, art, study skills, algebra prep, ACT/SAT prep, and work experience. The high school program served a total of 1,536 students, with 74 students having completed their graduation requirements at the end of the summer.

All academic summer school teachers received approximately 20 hours of professional development prior to the start of the six-week program. Kindergarten-Ready teachers as well as primary literacy and math teachers also had access to job embedded professional development. In 2013, there were 476 certified staff employed in SLA.Jennifer Cheatham:

Key Enhancements for Summer School 2014

A) Provide teachers with a pay increase without increasing overall cost of summer school.

Teacher salary increase of 3% ($53,887).

B) Smaller Learning Environments: Create smaller learning environments, with fewer students per summer school site compared to previous years, to achieve the following: increase student access to high quality learning, increase the number of students who can walk to school, and reduce number of people in the building when temperatures are high. ($50,482)

C) Innovations: Pilot at Wright Middle School and Lindbergh Elementary School where students receive instruction in a familiar environment, from a familiar teacher. These school sites were selected based on identification as intense focus schools along with having high poverty rates when compared to the rest of the district. Pilot character building curriculum at Sandburg Elementary School. ($37,529)

D) Student Engagement: Increase student engagement with high quality curriculum and instruction along with incentives such as Friday pep rallies and afternoon MSCR fieldtrips. ($25,000)

E) High School Professional Development: First-time-offered, to increase quality of instruction and student engagement in learning. ($12,083)

F) Student Selection: Utilize an enhanced student selection process that better aligns with school’s multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS) so that student services intervention teams (SSIT) have time to problem solve, and recommend students for SLA. Recommendations are based on student grades and standardized assessment scores, such as a MAP score below the 25th percentile at grades 3-5, or a score of minimal on the WKCE in language arts, math, science, and social studies at grades 3-5. (no cost)

Estimated total cost: $185,709.00

Summer School Program Reductions

The following changes would allow enhancements to summer school and implementation of innovative pilots:

A) Professional development (PD): reduce PD days for teachers grades K-8 by one day. This change will save money and provide teachers with an extra day off of work before the start of summer school (save $49,344.60).

B) Materials reduction: the purchase of Mondo materials in 2013 allows for the reduction of general literacy curricular materials in 2014 (save $5,000).

C) Madison Virtual Campus (MVC): MVC is not a reimbursable summer school program as students are not in classroom seats. This program could be offered separate from summer school in the future (save $18,000).

D) Librarians: reduce 3 positions, assigning librarians to support two sites. Students will continue to have access to the expertise of the librarian and can utilize library resources including electronic equipment (save $12,903.84).

E) Reading Interventionists: reduce 8 positions, as summer school is a student intervention, it allows students additional learning time in literacy and math. With new Mondo materials and student data profiles, students can be grouped for the most effective instruction when appropriate (save $48,492).

F) PBS Coach: reduce 8 positions, combining the coach and interventionist positions to create one position (coach/interventionist) that supports teachers in setting up classes and school wide systems, along with providing individual student interventions. With smaller learning sites, there would be less need for two separate positions (save $24,408).

G) Literacy and Math Coach Positions: reduce from 16 to 5 positions, combining the role and purpose of the literacy and math coach. Each position supports two schools for both math and literacy. Teachers can meet weekly with literacy/math coach to plan and collaborate around curriculum and student needs (save $27,601.60).

Estimated Total Savings: $185,750.04

Strategic Framework:

The role of the Summer Learning Academy (SLA) is critical to preparing students for college career and community readiness. Research tells us that over 50% of the achievement gap between lower and higher income students is directly related to unequal learning opportunities over the summer (Alexander et al., 2007). Research based practices and interventions are utilized in SLA to increase opportunities for learning and to raise student achievement across the District (Odden & Archibald, 2008). The SLA is a valuable time for students to receive additional support in learning core concepts in literacy and math to move them toward MMSD benchmarks (Augustine et.al., 2013). SLA aligns with the following Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) Strategic Framework goals:

A) Every student is on-track to graduate as measured by student growth and achievement at key milestones. Milestones of reading by grade 3, proficiency in reading and math in grade 5, high school readiness in grade 8, college readiness in grade 11, and high school graduation and completion rate.

B) Every student has access to challenging and well-rounded education as measured by programmatic access and participation data. Access to fine arts and world languages, extra-curricular and co-curricular activities, and advanced coursework.

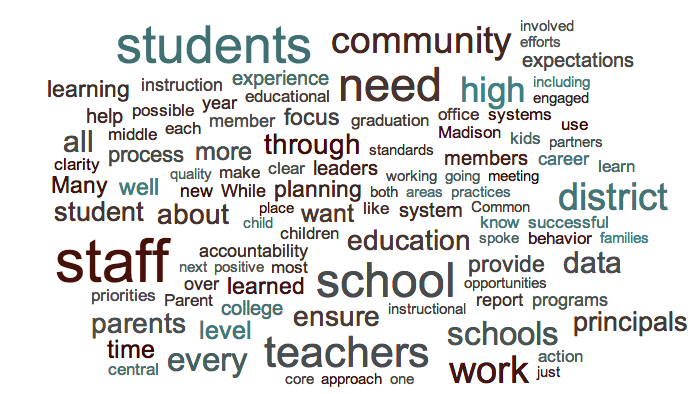

Madison Superintendent’s “Entry Process Report”

Madison Superintendent Jennifer Cheatham (PDF):Strengths

Overall Themes

Quality of teachers, principals, and central office staff: By and large, we have quality teachers, principals, support staff and central office staff who are committed to working hard on behalf of the children of Madison. With clarity of focus, support, and accountability, these dedicated educators will be able to serve our students incredibly well.

Commitment to action: Across the community and within schools, there is not only support for public education, but there is also an honest recognition of our challenges and an urgency to address them. While alarming gaps in student achievement exist, our community has communicated a willingness to change and a commitment to action.

Positive behavior: District-wide efforts to implement an approach to positive student behavior are clearly paying off. Student behavior is very good across the vast majority of schools and classrooms. Most students are safe and supported, which sets the stage for raising the bar for all students academically.

Promising practices: The district has some promising programs in place to challenge students academically, like our AVID/TOPS program at the middle and high school levels, the one-to-one iPad programs in several of our elementary schools, and our Dual Language Immersion programs. The district also does an incredibly successful job of inclusion and support of students with special needs. Generally, I’ve observed some of the most joyful and challenging learning environments I’ve ever seen.

Well-rounded education: Finally, the district offers a high level of access to the arts, sports, world language and other enriching activities that provide students with a well- rounded learning experience. This is a strength on which we can build.

“AVID is totally paying off. Kids, staff, everyone is excited about what it has brought to the school.” – Staff member

“Positive Behavior Support has made a dramatic improvement in teaching and the behavior expected. We’ve seen big changes in kids knowing what is expected and in us having consistent, schoolwide expectations”

– Staff member

Challenges

Focus: Principals, teachers and students have been experiencing an ever-changing and expanding set of priorities that make it difficult for them to focus on the day-to-day work of knowing every child well and planning instruction accordingly. If we are going to be successful, we need to be focused on a clear set of priorities aimed at measurable goals, and we need to sustain this focus over time.

“One of the strengths of MMSD is that we will try anything. The problem is that we opt out just as easily as we opt in. We don’t wait to see what things can really do.”

– Staff member

Coherence: In order for students to be successful, they need

to experience an education that leads them from Pre-Kindergarten through 12th grade, systematically and seamlessly preparing them for graduation and postsecondary education. We’ve struggled to provide our teachers with the right tools, resources and support to ensure that coherence for every child.

Personalized Learning: We need to work harder than ever to keep students engaged through a relevant and personalized education at the middle and high school levels. We’ve struggled to ensure that all students have an educational experience that gives them a glimpse of the bright futures. Personalized learning also requires increased access to and integrated use of technology.

Priority Areas

To capture as many voices as accurately as possible, my entry plan included a uniquely comprehensive analysis process. Notes from more than 100 meetings, along with other handouts, emails, and resources, were analyzed and coded for themes by Research & Program Evaluation staff. This data has been used to provide weekly updates to district leadership, content for this report and information to fuel the internal planning process that follows these visits.

The listening and learning phase has led us to five major areas to focus our work going forward. Over the next month, we’ll dive deeper into each of these areas to define the work, the action we need to take and how we’ll measure our progress. The following pages outline our priorities, what we learned to guide us to these priorities and where we’ll focus our planning in the coming month.Matthew DeFour collects a few comments, here.

Much more on Madison’s new Superintendent Jennifer Cheatham, here.

Dumb Kids’ Class

CATHOLIC SCHOOL was not the ordeal for me that it apparently was for many other children of my generation. I attended Catholic grade schools, served as an altar boy, and, astonishingly, was never struck by a nun or molested by a priest. All in all I was treated kindly, which often was more than I deserved. My education has withstood the test of time, including both the lessons my teachers instilled and the ones they never intended.

In the mid-20th century, when I was in grade school, a child’s self-esteem was not a matter for concern. Shame was considered a spur to better behavior and accomplishment. If you flunked a test, you were singled out, and the offending sheet of paper, bloodied with red marks, was waved before the entire class as a warning, much the way our catechisms depicted a boy with black splotches on his soul.

Fear was also considered useful. In the fourth grade, right around the time of the Cuban missile crisis, one of the nuns at St. Petronille’s, in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, told us that the Vatican had received a secret warning that the world would soon be consumed by a fatal nuclear exchange. The fact that the warning had purportedly been delivered by Our Lady of Fátima lent the prediction divine authority. (Any last sliver of doubt was removed by our viewing of the 1952 movie The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima, wherein the Virgin Mary herself appeared on a luminous cloud.) We were surely cooked. I remember pondering the futility of existence, to say nothing of the futility of safety drills that involved huddling under desks. When the fateful sirens sounded, I resolved, I would be out of there. Down the front steps, across Hillside Avenue, over fences, and through backyards, I would take the shortest possible route home, where I planned to crawl under my father’s workbench in the basement. It was the sturdiest thing I had ever seen. I didn’t believe it would save me, but after weighing the alternatives carefully, I decided it was my preferred spot to face oblivion.Related: English 10

AVID/TOPS Madison School District Findings 2011-2012

Wisconsin Center for the Advancement of Post-Secondary Education (2.6MB PDF):

To answer the guiding research questions, we developed a comparison group of academically and demographically similar non-participants to compare outcomes with AVID/TOPS students based on 8th grade pre-participation data. Using a statistical matching method called propensity score matching, we matched every AVID/TOPS student with a similar non-AVID/TOPS student at the same high school to create the comparison group.

Using these groups, we test for statistically and practically significant differences on key measures of academic preparation (cumulative GPA, enrollment and GPA in core courses, enrollment and GPA in AP/Honors courses, and credit attainment), college knowledge (test-taking rates and performance on the EXPLORE, PLAN, and ACT tests), and student engagement (attendance rates and behavioral referrals).

Statistically significant differences are differences that are unlikely to have occurred through random chance and are large enough to reflect meaningful differences in practice. In this report, we highlight statistically significant differences with a red symbol: .To focus attention on underrepresented students’ achievement, we disaggregated the measures by income and race. Though we report disaggregated findings, many of these groups are not mutually exclusive; for example, low-income students may also be African-American and therefore also represented in that data disaggregation. We do not report data from disaggregated groups that have fewer than five students in them. We then analyze this data at the program, grade cohort, and high school levels.

This assessment does not make causal claims about AVID/TOPS, nor does it present a longitudinal analysis of AVID/TOPS student achievement. Rather, the findings represent a single snapshot for achievement during the 2011-12 school year of the program’s 9th, 10th, and 11th graders.

What will it really take to Eliminate the Achievement Gap and Provide World-Class Schools for All Children in 2013 and beyond?

Kaleem Caire, via a kind email:

February 6, 2013

Dear Friends & Colleagues.

As the Board of Education deliberates on who the next Superintendent of the Madison Metropolitan School District will be, and as school districts in our state and across the nation wrestle with what to do to eliminate the racial achievement gap in education, while at the same time establishing world class schools that help prepare all children to learn, succeed and thrive in the 21st century, it’s important that we not lose sight of what the research continues to tell us really makes the difference in a child’s education.

More than 40 years of research on effective schools and transformational education have informed us that the key drivers for eliminating the racial achievement gap in schools and ensuring all students graduate from high school prepared for college and life continue to be:

- An Effective Teacher in Every Classroom – We must ensure every classroom is led by an effective teacher who is committed to and passionate about teaching young people, inspires all children to want to learn, has an appropriate depth of knowledge of the content they are teaching, is comfortable teaching and empowering diverse students, and coaches all of their students to high performance and expectations. Through its Race to the Top Initiative, the Obama Administration also defined an effective teacher as someone who can improve a students’ achievement by 1.0 grade levels in one school year while a highly effective teacher is someone who can improve student achievement by 1.5 grade levels annually. Schools with large numbers of students who are academically behind, therefore, should have the most effective teachers teaching them to ensure they catch up.

- High Quality, Effective Schools with Effective Leaders and Practices – Schools that are considered high quality have a combination of effective leaders, effective teachers, a rigorous curriculum, utilize data-driven instruction, frequently assess student growth and learning, offer a supportive and inspiring school culture, maintain effective governing boards and enjoy support from the broader community in which they reside. They operate with a clear vision, mission, core values and measurable goals and objectives that are monitored frequently and embraced by all in the school community. They also have principals and educators who maintain positive relationships with parents and each other and effectively catalyze and deploy resources (people, money, partnerships) to support student learning and teacher success. Schools that serve high poverty students also are most effective when they provide additional instructional support that’s aligned with what students are learning in the classroom each day, and engage their students and families in extended learning opportunities that facilitate a stronger connection to school, enable children to explore careers and other interests, and provide greater context for what students are learning in the classroom.

- Adequately Employed and Engaged Parents – The impact of parents’ socio-economic status on a child’s educational outcomes, and their emotional and social development, has been well documented by education researchers and educational psychologists since the 1960s. However, the very best way to address the issue of poverty among students in schools is to ensure that the parents of children attending a school are employed and earning wages that allow them to provide for the basic needs of their children. The most effective plans to address the persistent underachievement of low-income students, therefore, must include strategies that lead to quality job training, high school completion and higher education, and employment among parents. Parents who are employed and can provide food and shelter for their children are much more likely to be engaged in their children’s education than those who are not. Besides being employed, parents who emphasize and model the importance of learning, provide a safe, nurturing, structured and orderly living environment at home, demonstrate healthy behaviors and habits in their interactions with their children and others, expose their children to extended learning opportunities, and hold their children accountable to high standards of character and conduct generally rear children who do well in school. Presently, 74% of Black women and 72% of white women residing in Dane County are in the labor force; however, black women are much more likely to be unemployed and looking for work, unmarried and raising children by themselves, or working in low wage jobs even if they have a higher education.

- Positive Peer Relationships and Affiliations – A child’s peer group can have an extraordinarily positive, or negative, affect on their persistence and success in school. Students who spend time with other students who believe that learning and attending school is important, and who inspire and support each other, generally spend more time focused on learning in class, more time studying outside of class, and tend to place a higher value on school and learning overall. To the contrary, children who spend a lot of time with peer groups that devalue learning, or engage in bullying, are generally at a greater risk of under-performing themselves. Creating opportunities and space for positive peer relationships to form and persist within and outside of school can lead to significantly positive outcomes for student achievement.

- Community Support and Engagement – Children who are reared in safe and resourceful communities that celebrate their achievements, encourage them to excel, inform them that they are valued, hold them accountable to a high standard of character and integrity, provide them with a multitude of positive learning experiences, and work together to help them succeed rarely fail to graduate high school and are more likely to pursue higher education, regardless of their parents educational background. “It Takes A Whole Village to Raise a Child” is as true of a statement now as it was when the African proverb was written in ancient times. Unfortunately, as children encounter greater economic and social hardships, such as homelessness, joblessness, long-term poverty, poor health, poor parenting and safety concerns, the village must be stronger, more uplifting and more determined than ever to ensure these children have the opportunity to learn and remain hopeful. It is often hopelessness that brings us down, and others along with us.

If we place all of our eggs in just one of the five baskets rather than develop strategies that bring together all five areas that affect student outcomes, our efforts to improve student performance and provide quality schools where all children succeed will likely come up short. This is why the Urban League of Greater Madison is working with its partners to extend the learning time “in school” for middle schoolers who are most at-risk of failing when they reach high school, and why we’ll be engaging their parents in the process. It’s also why we’ve worked with the United Way and other partners to strengthen the Schools of Hope tutoring initiative for the 1,600 students it serves, and why we are working with local school districts to help them recruit effective, diverse educators and ensure the parents of the children they serve are employed and have access to education and job training services. Still, there is so much more to be done.

As a community, I strongly believe we can achieve the educational goals we set for our chlidren if we focus on the right work, invest in innovation, take a “no excuses” approach to setting policy and getting the work done, and hire a high potential, world-class Superintendent who can take us there.

God bless our children, families, schools and capital region.

Onward!

Kaleem Caire

President & CEO

Urban League of Greater Madison

Phone: 608-729-1200

Assistant: 608-729-1249

Fax: 608-729-1205

www.ulgm.orgRelated: Kaleem Caire interview, notes and links along with the proposed Madison Preparatory IB Charter school (rejected by a majority of the Madison School Board).

In jeopardy: Open government in Washington State

Laurie Rogers, via a kind email:

Dear Colleagues and Friends:

The citizens of Washington State need your help in defending the principle of open government.

Last week, I wrote an article for my blog “Betrayed” about how the board of Spokane Public Schools is again attempting to modify the Public Records Act in ways that would undermine the Act for citizens across the entire State of Washington. That article is found here: http://betrayed-whyeducationisfailing.blogspot.com/p/by-laurie-h.html

One of the bills introduced this year regarding the Public Records Act is HB 1128, a bill that would essentially gut the Public Records Act for citizens and whistleblowers. HB 1128 would make it nearly impossible to obtain records that agencies do not want to release. It was theoretically written to protect and defend public agencies against abusive records requesters; it was not written to protect or defend citizens against abusive agencies.

On Jan. 25, HB 1128 was discussed in a legislative hearing. All of the pro-HB 1128 arguments were made by public officials, including Spokane County Commissioner Todd Mielke. Nearly all complained about vindictive behavior by former public employees. Meanwhile, all arguments made in opposition to HB 1128 were made by non-government people who spoke up for the principle of open government and the right of citizens to hold their government agencies accountable.

Legislators wisely elected to revisit the language of HB 1128, so we have a brief opportunity to influence this process. I’ve written an analysis of HB 1128, which I’ve pasted below and attached in a PDF file. You will see that the impact of HB 1128 would be devastating for open-government in Washington State and for all citizens. I also have serious worries about future bills regarding the Public Records Act.

All comments and suggestions are welcome. You also are welcome to quote or forward this email and the analysis as you wish.

If the language in any new legislation regarding the Public Records Act and other open-government laws doesn’t protect the rights of citizens and whistleblowers, I guarantee that language will be used against us. Please help us to maintain open government in Washington State. Please ask your legislators, your friends and your colleagues to stand up against HB 1128, against the language in HB 1128, and against any other bills that would negatively affect the principle of open government in this state.

There are other ways to accomplish what the authors of HB 1128 intended. Tim Ford, the open-government ombudsman in the Attorney General’s Office, would be a great point of contact on how to do it.

Thank you for your help. Please see the analysis below or attached.

Laurie Rogers

Spokane, WA

wlroge@comcast.net

Abolish Social Studies

Michael Knox Beran, via Will Fitzhugh:

Emerging as a force in American education a century ago, social studies was intended to remake the high school. But its greatest effect has been in the elementary grades, where it has replaced an older way of learning that initiated children into their culture [and their History?] with one that seeks instead to integrate them into the social group. The result was a revolution in the way America educates its young. The old learning used the resources of culture to develop the child’s individual potential; social studies, by contrast, seeks to adjust him to the mediocrity of the social pack.

Why promote the socialization of children at the expense of their individual development? A product of the Progressive era, social studies ripened in the faith that regimes guided by collectivist social policies could dispense with the competitive striving of individuals and create, as educator George S. Counts wrote, “the most majestic civilization ever fashioned by any people.” Social studies was to mold the properly socialized citizens of this grand future. The dream of a world regenerated through social planning faded long ago, but social studies persists, depriving children of a cultural rite of passage that awakened what Coleridge called “the principle and method of self-development” in the young.

The poverty of social studies would matter less if children could make up its cultural deficits in English [and History?] class. But language instruction in the elementary schools has itself been brought into the business of socializing children and has ceased to use the treasure-house of culture to stimulate their minds. As a result, too many students today complete elementary school with only the slenderest knowledge of a culture that has not only shaped their civilization but also done much to foster individual excellence.

In 1912, the National Education Association, today the largest labor union in the United States, formed a Committee on the Social Studies. In its 1916 report, The Social Studies in Secondary Education, the committee opined that if social studies (defined as studies that relate to “man as a member of a social group”) took a place in American high schools, students would acquire “the social spirit,” and “the youth of the land” would be “steadied by an unwavering faith in humanity.” This was an allusion to the “religion of humanity” preached by the French social thinker Auguste Comte, who believed that a scientifically trained ruling class could build a better world by curtailing individual freedom in the name of the group. In Comtian fashion, the committee rejected the idea that education’s primary object was the cultivation of the individual intellect. “Individual interests and needs,” education scholar Ronald W. Evans writes in his book The Social Studies Wars, were for the committee “secondary to the needs of society as a whole.”

The Young Turks of the social studies movement, known as “Reconstructionists” because of their desire to remake the social order, went further. In the 1920s, Reconstructionists like Counts and Harold Ordway Rugg argued that high schools should be incubators of the social regimes of the future. Teachers would instruct students to “discard dispositions and maxims” derived from America’s “individualistic” ethos, wrote Counts. A professor in Columbia’s Teachers College and president of the American Federation of Teachers, Counts was for a time enamored of Joseph Stalin. After visiting the Soviet Union in 1929, he published A Ford Crosses Soviet Russia, a panegyric on the Bolsheviks’ “new society.” Counts believed that in the future, “all important forms of capital” would “have to be collectively owned,” and in his 1932 essay “Dare the Schools Build a New Social Order?,” he argued that teachers should enlist students in the work of “social regeneration.”

Like Counts, Rugg, a Teachers College professor and cofounder of the National Council for the Social Studies, believed that the American economy was flawed because it was “utterly undesigned and uncontrolled.” In his 1933 book The Great Technology, he called for the “social reconstruction” and “scientific design” of the economy, arguing that it was “now axiomatic that the production and distribution of goods can no longer be left to the vagaries of chance–specifically to the unbridled competitions of self-aggrandizing human nature.” There “must be central control and supervision of the entire [economic] plant” by “trained and experienced technical personnel.” At the same time, he argued, the new social order must “socialize the vast proportion” of wealth and outlaw the activities of “middlemen” who didn’t contribute to the “production of true value.”

Rugg proposed “new materials of instruction” that “shall illustrate fearlessly and dramatically the inevitable consequence of the lack of planning and of central control over the production and distribution of physical things. . . . We shall disseminate a new conception of government–one that will embrace all of the collective activities of men; one that will postulate the need for scientific control and operation of economic activities in the interest of all people; and one that will successfully adjust the psychological problems among men.”

Rugg himself set to work composing the “new materials of instruction.” In An Introduction to Problems of American Culture, his 1931 social studies textbook for junior high school students, Rugg deplored the “lack of planning in American life”:

“Repeatedly throughout this book we have noted the unplanned character of our civilization. In every branch of agriculture, industry, and business this lack of planning reveals itself. For instance, manufacturers in the United States produce billions’ of dollars worth of goods without scientific planning. Each one produces as much as he thinks he can sell, and then each one tries to sell more than his competitors. . . . As a result, hundreds of thousands of owners of land, mines, railroads, and other means of transportation and communication, stores, and businesses of one kind or another, compete with one another without any regard for the total needs of all the people. . . . This lack of national planning has indeed brought about an enormous waste in every outstanding branch of industry. . . . Hence the whole must be planned.

Rugg pointed to Soviet Russia as an example of the comprehensive control that America needed, and he praised Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan, which resulted in millions of deaths from famine and forced labor. The “amount of coal to be mined each year in the various regions of Russia,”

Rugg told the junior high schoolers reading his textbook,

“is to be planned. So is the amount of oil to be drilled, the amount of wheat, corn, oats, and other farm products to be raised. The number and size of new factories, power stations, railroads, telegraph and telephone lines, and radio stations to be constructed are planned. So are the number and kind of schools, colleges, social centers, and public buildings to be erected. In fact, every aspect of the economic, social, and political life of a country of 140,000,000 people is being carefully planned! . . . The basis of a secure and comfortable living for the American people lies in a carefully planned economic life.”

During the 1930s, tens of thousands of American students used Rugg’s social studies textbooks.

Toward the end of the decade, school districts began to drop Rugg’s textbooks because of their socialist bias. In 1942, Columbia historian Allan Nevins further undermined social studies’ premises when he argued in The New York Times Magazine that American high schools were failing to give students a “thorough, accurate, and intelligent knowledge of our national past–in so many ways the brightest national record in all world history.” Nevins’s was the first of many critiques that would counteract the collectivist bias of social studies in American high schools, where “old-fashioned” history classes have long been the cornerstone of the social studies curriculum.

Yet possibly because school boards, so vigilant in their superintendence of the high school, were not sure what should be done with younger children, social studies gained a foothold in the primary school such as it never obtained in the secondary school. The chief architect of elementary school social studies was Paul Hanna, who entered Teachers College in 1924 and fell under the spell of Counts and Rugg. “We cannot expect economic security so long as the [economic] machine is conceived as an instrument for the production of profits for private capital rather than as a tool functioning to release mankind from the drudgery of work,” Hanna wrote in 1933.

Hanna was no less determined than Rugg to reform the country through education. “Pupils must be indoctrinated with a determination to make the machine work for society,” he wrote. His methods, however, were subtler than Rugg’s. Unlike Rugg’s textbooks, Hanna’s did not explicitly endorse collectivist ideals. The Hanna books contain no paeans to central planning or a command economy. On the contrary, the illustrations have the naive innocence of the watercolors in Scott Foresman’s Dick and Jane readers. The books depict an idyllic but familiar America, rich in material goods and comfortably middle-class; the fathers and grandfathers wear suits and ties and white handkerchiefs in their breast pockets.

Not only the pictures but the lessons in the books are deceptively innocuous. It is in the back of the books, in the notes and “interpretive outlines,” that Hanna smuggles in his social agenda by instructing teachers how each lesson is to be interpreted so that children learn “desirable patterns of acting and reacting in democratic group living.” A lesson in the second-grade text Susan’s Neighbors at Work, for example, which describes the work of police officers, firefighters, and other public servants, is intended to teach “concerted action” and “cooperation in obeying commands and well-thought-out plans which are for the general welfare.” A lesson in Tom and Susan, a first-grade text, about a ride in grandfather’s red car is meant to teach children to move “from absorption in self toward consideration of what is best in a group situation.” Lessons in Peter’s Family, another first-grade text, seek to inculcate the idea of “socially desirable” work and “cooperative labor.”

Hanna’s efforts to promote “behavior traits” conducive to “group living” would be less objectionable if he balanced them with lessons that acknowledge the importance of ideals and qualities of character that don’t flow from the group–individual exertion, liberty of action, the necessity at times of resisting the will of others. It is precisely Coleridge’s principle of individual “self-development” that is lost in Hanna’s preoccupation with social development. In the Hanna books, the individual is perpetually sunk in the impersonality of the tribe; he is a being defined solely by his group obligations. The result is distorting; the Hanna books fail to show that the prosperous America they depict, if it owes something to the impulse to serve the community, owes as much, or more, to the free striving of individuals pursuing their own ends.

Hanna’s spirit is alive and well in the American elementary school. Not only Scott Foresman but other big scholastic publishers–among them Macmillan/McGraw-Hill and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt–publish textbooks that dwell continually on the communal group and on the activities that people undertake for its greater good. Lessons from Scott Foresman’s second-grade textbook Social Studies: People and Places (2003) include “Living in a Neighborhood,” “We Belong to Groups,” “A Walk Through a Community,” “How a Community Changes,” “Comparing Communities,” “Services in Our Community,” “Our Country Is Part of Our World,” and “Working Together.” The book’s scarcely distinguishable twin, Macmillan/McGraw-Hill’s We Live Together (2003), is suffused with the same group spirit. Macmillan/McGraw-Hill’s textbook for third-graders, Our Communities (2003), is no less faithful to the Hanna model. The third-grade textbooks of Scott Foresman and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (both titled Communities) are organized on similar lines, while the fourth-grade textbooks concentrate on regional communities. Only in the fifth grade is the mold shattered, as students begin the sequential study of American history; they are by this time in sight of high school, where history has long been paramount.

Today’s social studies textbooks will not turn children into little Maoists. The group happy-speak in which they are composed is more fatuous than polemical; Hanna’s Reconstructionist ideals have been so watered down as to be little more than banalities. The “ultimate goal of the social studies,” according to Michael Berson, a coauthor of the Houghton Mifflin Harcourt series, is to “instigate a response that spreads compassion, understanding, and hope throughout our nation and the global community.” Berson’s textbooks, like those of the other publishers, are generally faithful to this flabby, attenuated Comtism.

Yet feeble though the books are, they are not harmless. Not only do they do too little to acquaint children with their culture’s ideals of individual liberty and initiative; they promote the socialization of the child at the expense of the development of his own individual powers. The contrast between the old and new approaches is nowhere more evident than in the use that each makes of language. The old learning used language both to initiate the child into his culture and to develop his mind. Language and culture are so intimately related that the Greeks, who invented Western primary education, used the same word to designate both: paideia signifies both culture and letters (literature). The child exposed to a particular language gains insight into the culture that the language evolved to describe–for far from being an artifact of speech only, language is the master light of a people’s thought, character, and manners. At the same time, language–particularly the classic and canonical utterances of a people, its primal poetry–[and its History?] has a unique ability to awaken a child’s powers, in part because such utterances, Plato says, sink “furthest into the depths of the soul.”

Social studies, because it is designed not to waken but to suppress individuality, shuns all but the most rudimentary and uninspiring language. Social studies textbooks descend constantly to the vacuity of passages like this one, from People and Places:

“Children all around the world are busy doing the same things. They love to play games and enjoy going to school. They wish for peace. They think that adults should take good care of the Earth. How else do you think these children are like each other? How else do you think they are like you?”

The language of social studies is always at the same dead level of inanity. There is no shadow or mystery, no variation in intensity or alteration of pitch–no romance, no refinement, no awe or wonder. A social studies textbook is a desert of linguistic sterility supporting a meager scrub growth of commonplaces about “community,” “neighborhood,” “change,” and “getting involved.” Take the arid prose in Our Communities:

“San Antonio, Texas, is a large community. It is home to more than one million people, and it is still growing. People in San Antonio care about their community and want to make it better. To make room for new roads and houses, many old trees must be cut down. People in different neighborhoods get together to fix this by planting.”

It might be argued that a richer and more subtle language would be beyond third-graders. Yet in his Third Eclectic Reader, William Holmes McGuffey, a nineteenth-century educator, had eight-year-olds reading Wordsworth and Whittier. His nine-year-olds read the prose of Addison, Dr. Johnson, and Hawthorne and the poetry of Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, Southey, and Bryant. His ten-year-olds studied the prose of Sir Walter Scott, Dickens, Sterne, Hazlitt, and Macaulay [History] and the poetry of Pope, Longfellow, Shakespeare, and Milton.

McGuffey adapted to American conditions some of the educational techniques that were first developed by the Greeks. In fifth-century BC Athens, the language of Homer and a handful of other poets formed the core of primary education. With the emergence of Rome, Latin became the principal language of Western culture and for centuries lay at the heart of primary- and grammar-school education. McGuffey had himself received a classical education, but conscious that nineteenth-century America was a post-Latin culture, he revised the content of the old learning even as he preserved its underlying technique of using language as an instrument of cultural initiation and individual self-development. He incorporated, in his Readers, not canonical Latin texts but classic specimens of English prose and poetry [and History].

Because the words of the Readers bit deep–deeper than the words in today’s social studies textbooks do–they awakened individual potential. The writer Hamlin Garland acknowledged his “deep obligation” to McGuffey “for the dignity and literary grace of his selections. From the pages of his readers I learned to know and love the poems of Scott, Byron, Southey, and Words- worth and a long line of the English masters. I got my first taste of Shakespeare from the selected scenes which I read in these books.” Not all, but some children will come away from a course in the old learning stirred to the depths by the language of Blake or Emerson. But no student can feel, after making his way through the groupthink wastelands of a social studies textbook, that he has traveled with Keats in the realms of gold.

It might be objected that primers like the McGuffey Readers were primarily intended to instruct children in reading and writing, something that social studies doesn’t pretend to do. In fact, the Readers, like other primers of the time, were only incidentally language manuals. Their foremost function was cultural: they used language both to introduce children to their cultural heritage [including their History] and to stimulate their individual self-culture. The acultural, group biases of social studies might be pardonable if cultural learning continued to have a place in primary-school English instruction. But primary-school English–or “language arts,” as it has come to be called–no longer introduces children, as it once did, to the canonical language of their culture; it is not uncommon for public school students today to reach the fifth grade without having encountered a single line of classic English prose or poetry. Language arts has become yet another vehicle for the socialization of children. A recent article by educators Karen Wood and Linda Bell Soares in The Reading Teacher distills the essence of contemporary language-arts instruction, arguing that teachers should cultivate not literacy in the classic sense but “critical literacy,” a “pedagogic approach to reading that focuses on the political, sociocultural, and economic forces that shape young students’ lives.”

For educators devoted to the social studies model, the old learning is anathema precisely because it liberates individual potential. It releases the “powers of a young soul,” the classicist educator Werner Jaeger wrote, “breaking down the restraints which hampered it, and leading into a glad activity.” The social educators have revised the classic ideal of education expressed by Pindar: “Become what you are” has given way to “Become what the group would have you be.” Social studies’ verbal drabness is the means by which its contrivers starve the self of the sustenance that nourishes individual growth. A stunted soul can more easily be reduced to an acquiescent dullness than a vital, growing one can; there is no readier way to reduce a people to servile imbecility than to cut them off from the traditions of their language [and their History], as the Party does in George Orwell’s 1984.

Indeed, today’s social studies theorists draw on the same social philosophy that Orwell feared would lead to Newspeak. The Social Studies Curriculum: Purposes, Problems, and Possibilities, a 2006 collection of articles by leading social studies educators, is a socialist smorgasbord of essays on topics like “Marxism and Critical Multicultural Social Studies” and “Decolonizing the Mind for World-Centered Global Education.” The book, too, reveals the pervasive influence of Marxist thinkers like Peter McLaren, a professor of urban schooling at UCLA who advocates “a genuine socialist democracy without market relations,” venerates Che Guevara as a “secular saint,” and regards the individual “self” as a delusion, an artifact of the material “relations which produced it”–“capitalist production, masculinist economies of power and privilege, Eurocentric signifiers of self/other identifications,” all the paraphernalia of bourgeois imposture. For such apostles of the social pack, Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” Milton’s and Tennyson’s “soul within,” Spenser’s “my self, my inward self I mean,” and Wordsworth’s aspiration to be “worthy of myself” are expressions of naive faith in a thing that dialectical materialism has revealed to be an accident of matter, a random accumulation of dust and clay.

The test of an educational practice is its power to enable a human being to realize his own promise in a constructive way. Social studies fails this test. Purge it of the social idealism that created and still inspires it, and what remains is an insipid approach to the cultivation of the mind, one that famishes the soul even as it contributes to what Pope called the “progress of dulness.” It should be abolished.

From Self-Flying Helicopters to Classrooms of the Future

n a summer day four years ago, a Stanford University computer-science professor named Andrew Ng held an unusual air show on a field near the campus. His fleet of small helicopter drones flew under computer control, piloted by artificial-intelligence software that could teach itself to fly after watching a human operator. By the end of the day, the copters were hot-dogging–flipping, rolling, even hovering upside down.

It was a milestone for the field of “machine learning,” the same area of artificial intelligence that lets Amazon recommend books based on a shopper’s previous habits and helps Google tailor search results to a user’s behavior. Mr. Ng and his team of graduate students showed that artificial-intelligence software could control one of the hardest-to-maneuver vehicles and keep it stable while flying at 45 miles an hour. That same year, Technology Review, published by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, included Mr. Ng among the top 35 innovators in the world under the age of 35.

Today Mr. Ng is an innovator in an entirely different setting: online education. He is a founder of the start-up Coursera, which works with 33 colleges to help them deliver free online courses. After less than a year of operation, the company already claims more students–1.3 million–than just about any educational institution on the planet. Mr. Ng likes to say that Coursera arrived at an “inflection point” for the idea of massive open online courses, or MOOC’s, which are designed so a single professor can teach tens of thousands of students at a time.

Dumb Kids’ Class: The benefits of being underestimated by the nuns at St. Petronille’s

Catholic school was not the ordeal for me that it apparently was for many other children of my generation. I attended Catholic grade schools, served as an altar boy, and, astonishingly, was never struck by a nun or molested by a priest. All in all I was treated kindly, which often was more than I deserved. My education has withstood the test of time, including both the lessons my teachers instilled and the ones they never intended.

In the mid-20th century, when I was in grade school, a child’s self-esteem was not a matter for concern. Shame was considered a spur to better behavior and accomplishment. If you flunked a test, you were singled out, and the offending sheet of paper, bloodied with red marks, was waved before the entire class as a warning, much the way our catechisms depicted a boy with black splotches on his soul.

Fear was also considered useful. In the fourth grade, right around the time of the Cuban missile crisis, one of the nuns at St. Petronille’s, in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, told us that the Vatican had received a secret warning that the world would soon be consumed by a fatal nuclear exchange. The fact that the warning had purportedly been delivered by Our Lady of Fátima lent the prediction divine authority. (Any last sliver of doubt was removed by our viewing of the 1952 movie The Miracle of Our Lady of Fatima, wherein the Virgin Mary herself appeared on a luminous cloud.) We were surely cooked. I remember pondering the futility of existence, to say nothing of the futility of safety drills that involved huddling under desks. When the fateful sirens sounded, I resolved, I would be out of there. Down the front steps, across Hillside Avenue, over fences, and through backyards, I would take the shortest possible route home, where I planned to crawl under my father’s workbench in the basement. It was the sturdiest thing I had ever seen. I didn’t believe it would save me, but after weighing the alternatives carefully, I decided it was my preferred spot to face oblivion.

Stephens Elementary (Madison) school parents concerned after high schooler found asleep with pot pipe

After a high school student was found unresponsive in a West Side elementary school bathroom with a marijuana pipe in his backpack, parents are questioning why an alternative school program for academically at-risk high school students is in the same building as the elementary school.

“It does raise concerns,” said Becky Ketarkus, who has six children enrolled at Stephens Elementary, 120 S. Rosa Road. “I’d love to know what the plan is for the future to make sure the school is safe.”

Superintendent Dan Nerad answered that the program is not unique — two other elementary schools house alternative programs for high schoolers — and the district has had relatively few problems similar to the incident on Monday. He stressed that, unlike some other alternative programs, those in elementary schools are targeted to academically at-risk students, not those with behavior issues.

Madison’s Phoenix Program Review

Madison School District (150K PDF):

Basic Information

The Phoenix program began serving students in the fall of 2010-11. The Phoenix program was housed in the Doyle Administration Building

During this school year the program served

35 middle school students and

33 high school students

28 middle school students progressed through the Phoenix program and returned to an MMSD educational environment

24 high school students progressed through the Phoenix program and returned to an MMSD educational environment

7 middle students were expelled from the Phoenix program due to behavioral issues 9 high students were expelled from the Phoenix program due to behavioral issues

Curriculum

The first year the curriculum consisted of on-line academics supported by additional resource material.

Each quarter a student could receive up to a .25 credit in Community Service, Career Planning, English, Writing, Math, Physical Education, Science, Social Studies

The program’s partnership with community FACE and district PBST staff allowed the students to participate in social emotional skill development forty-five hours per week.Much more on the “Phoenix Program”, here.

P.S. This Madison School District document includes a header that I’ve not seen before: “Innovative Education”. I also noticed that the District (or someone) placed a billboard on the Beltline marketing Cherokee Middle School’s Arts education.

Madison Schools’ dual-language program prompts concerns

Students in the Madison School District’s dual-language immersion program are less likely than students in English-only classrooms to be black or Asian, come from low-income families, need special education services or have behavioral problems, according to a district analysis.

School Board members have raised concerns about the imbalance of diversity and other issues with the popular program.

As a result, Superintendent Dan Nerad wants to put on hold expansion plans at Hawthorne, Stephens and Thoreau elementaries and delay the decision to the spring on how to expand the program to La Follette High School in 2013.

“While the administration remains committed to the (dual-language) program and to the provision of bilingual programming options for district students, I believe there is substantial value in identifying, considering and responding to these concerns,” Nerad wrote in a memo to the board.

In Madison’s program, both native English and Spanish speakers receive 90 percent of their kindergarten instruction in Spanish, with the mix steadily increasing to 50-50 by fourth grade.

Madison Preparatory IB Charter School School Board Discussion Notes

Madison Preparatory Academy will receive the first half of a $225,000 state planning grant after the Madison School Board determined Thursday that the revised proposal for the charter school addresses legal concerns about gender equality.

Madison Schools Superintendent Dan Nerad announced the decision following a closed School Board meeting.

Questions still remain about the cost of the proposal by the Urban League of Greater Madison, which calls for a school for 60 male and 60 female sixth-graders geared toward low-income minorities that would open next year.

“I understand the heartfelt needs for this program,” Nerad said, but “there are other needs we need to address.”

Madison School Board Member Ed Hughes

The school district does not have a lot of spare money lying around that it can devote to Madison Prep. Speaking for myself, I am not willing to cut educational opportunities for other students in order to fund Madison Prep. If it turns out that entering into a five-year contract with Madison Prep would impose a net cost of millions of dollars on the school district, then, for me, we’d have to be willing to raise property taxes by that same millions of dollars in order to cover the cost.

It is not at all clear that we’d be able to do this even if we wanted to. Like all school districts in the state, MMSD labors under the restrictions of the state-imposed revenue caps. The law places a limit on how much school districts can spend. The legislature determines how that limit changes from year to year. In the best of times, the increase in revenues that Wisconsin school districts have been allowed have tended to be less than their annual increases in costs. This has led to the budget-slashing exercises that the school districts endure annually.

In this environment, it is extremely difficult to see how we could justify taking on the kind of multi-million dollar obligation that entering into a five-year contract with Madison Prep would entail. Indeed, given the projected budget numbers and revenue limits, it seems inevitable that signing on to the Madison Prep proposal would obligate the school district to millions of dollars in cuts to the services we provide to our students who would not attend Madison Prep.

A sense of the magnitude of these cuts can be gleaned by taking one year as an example. Since Madison Prep would be adding classes for seven years, let’s look at year four, the 2015-16 school year, which falls smack dab in the middle.Last night I (TJ) was asked to leave the meeting on African American issues in the Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) advertised as being facilitated by the Department of Justice Community Relations Service (DOJ CRS) and hosted or convened by the Urban League of Greater Madison (ULGM) with the consent and participation of MMSD. I was told that if I did not leave, the meeting would be canceled. The reason given was that I write a blog (see here for some background on the exclusion of the media and bloggers and here for Matt DeFour’s report from outside the meeting).

I gave my word that I would not write about the meeting, but that did not alter the request. I argued that as a parent and as someone who has labored for years to address inequities in public education, I had both a legitimate interest in being there and the potential to contribute to the proceedings. This was acknowledged and I was still asked to leave and told again that the meeting would not proceed if I did not leave. I asked to speak to the DOJ CRS representatives in order to confirm that this was the case and this request was repeatedly refused by Kaleem Caire of the ULGM.The Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel:

An idea hatched in Madison aims to give parents with boys in Wisconsin’s second-largest city another positive option for their children. It’s an idea that ought to be channeled to Milwaukee.

Madison Preparatory Academy for Young Men would feature the rigorous International Baccalaureate program, longer days, a longer school year and lofty expectations for dress and behavior for boys in sixth grade through high school. And while it would accept all comers, clearly it is designed to focus on low-income boys of color. Backers hope to open a year from now.

One of the primary movers behind Madison Prep is Kaleem Caire, the head of the Urban League of Madison, who grew up in the city and attended Madison West High School in 1980s, Alan J. Borsuk explained in a column last Sunday. Caire later worked in Washington, D.C., as an education advocate before returning to Madison.

Caire saw too many young black men wash out and end up either dead or in jail, reported Borsuk, a senior fellow in law and public policy at Marquette University Law School. And Caire now is worried, as are we, about the atrocious statistics that place young black boys so far behind their white peers.The Department of Justice official explained the shadowy, confidential nature of the Community Relations Service to the audience by describing the kinds of situations it intervenes in, mostly having to do with hate crimes and rioting. He said in no uncertain terms, “We are not here to do an investigation,” and even asked for the audience members to repeat the sentence with him. He then went on to ask for people to respect the confidentiality of those raising issues, and laid out the structure of the meeting: 30 minutes for listing problems relating to the achievement gap and 45 minutes generating solutions.

I will respect the confidentiality of the content of the meeting by not repeating it. However, I will say that what was said in that room was no different that what has been said at countless other open, public meetings with the School District and in community groups on the same topic, the only difference being that there were far fewer parents in the room and few if any teachers.

It turned out that the Department of Justice secretive meeting was a convenient way to pack the house with a captive audience for yet another infomercial about Madison Prep. Kaleem Caire adjourned the one meeting and immediately convened an Urban League meeting where he gave his Madison Prep sales pitch yet again. About 1/3 of the audience left at that point.

Madison Schools: Alternative School Redesign (Hoyt, Whitehorse & Cherokee “Mental Health Hubs”) to Address Mental Health Concerns: Phase 1

80K PDF, via a kind reader’s email:

I. Introduction A. Title/topic -Alternative Redesign to Address Mental Health Concerns B. Presenter/contact person- Sue Abplanalp, John Harper, Pam Nash and Nancy Yoder

Background information -The Purpose of this Proposal: Research shows that half of all lifetime cases of mental illness begin by age 14.1 Scientists are discovering that changes in the body leading to mental illness may start much earlier, before any symptoms appear.

Helping young children and their parents manage difficulties early in life may prevent the development of disorders. Once mental illness develops, it becomes a regular part of a child’s behavior and more difficult to treat. Even though doctors know how to treat (though not yet cure) many disorders, a majority of children with mental illnesses are not getting treatment (National Institute of Mental Health).

II. Summary of Current Information: Success is defined as the achievement ofsomething desired and planned. As a steering committee, our desire and plan is to promote a strategic hub in three sites (Hoyt, Whitehorse and Cherokee) that connect, support and sustain students with mental health issues in a more inclusive environment with appropriate professionals, in order to maximize students’ success in middle school and help them achieve their aspirations in a setting that is appropriate for their needs. The new site will also offer mini clinics from a community provider

Current Status: Currently, there is one program housed at Hoyt that serves 28-30 students in self contained settings. There is currently a ratio of 1:4 with 4 staff and 4 special educational assistants assigned to the program. In addition, there is a Cluster Program housed at Sherman with 2 adults and 6-7 students in the program.

Proposal: This proposal leaves approximately half of the students and staff at the current Hoyt site (those students who pose more of a danger to self or others) and removes all of the students and staff from Sherman (no program at Sherman) to the new sites. Students will attend either Whitehorse or Cherokee Middle Schools with a program that provides ongoing professional help and is more inclusive as students will be assigned to homerooms and classes, with alternative settings in the school to support them when they need a more restrictive environment with support from a smaller student ratio and a psychologist or social worker that is assigned to the team.This initiative was discussed during Monday evening’s Madison School Board meeting. Watch the discussion here (beginning at 180 minutes).

Why 4-K is a good idea

Mary was four years old when she entered the pre-kindergarten program in Marshall. Her parents were struggling with her behavior. She had a significant speech delay. She didn’t like snuggling with them. She didn’t want to read books. And she refused to let her parents touch her hair.

“What are we doing wrong?” her parents wondered.

Mary’s early childhood teachers worked with her parents and her pediatrician to help diagnose the problem: Mary had autism. Her teachers created a special education plan for her, which included “social stories” — books of pictures from Mary’s daily life that helped explain mysterious rituals like brushing her hair.

The teachers taught Mary how to read facial expressions and verbalize her feelings, instead of having tantrums. They took her on field trips to public places, so she could get used to the noise and bustle of other people.

As Mary’s parents began to understand autism, the teachers supported them by offering advice. The intense, early intervention helped Mary and her family learn to manage her autism. By sixth grade, Mary was doing so well she was able to exit special education services for good.Much more on Madison’s planned 4k program, here.

Gov. Doyle: Announces 71,400 students have signed the Wisconsin Covenant

Governor Jim Doyle today announced that 18,264 students signed the Wisconsin Covenant Pledge in the fourth year of the program, bringing the total number of students who have signed the pledge and indicated that they plan to go on to college to more than 71,400 students across the state. The first class of students to sign the pledge are currently seniors in high school and preparing to make the transition to college next fall.

“I am encouraged that so many students have signed the Wisconsin Covenant and chosen the path to higher education that will help train them for the high-paying, technical jobs we need to compete in the global economy,” Governor Doyle said. “Regardless of their family’s economic background, their past academic behavior, and whether anyone in their family has a college degree, all students need to know that higher education is an option for them.”

Students who participate in the Wisconsin Covenant sign a pledge affirming that they will earn a high school diploma, participate in their community, take a high school curriculum that prepares them for higher education, maintain at least a B average in high school, and apply for state and federal financial aid.

The Backstory on the Madison West High Protest

Madison School Board Member Ed Hughes:

IV. The Rollout of the Plan: The Plotlines Converge

I first heard indirectly about this new high school plan in the works sometime around the start of the school year in September. While the work on the development of the plan continued, the District’s responses to the various sides interested in the issue of accelerated classes for 9th and 10th grade students at West was pretty much put on hold.

This was frustrating for everyone. The West parents decided they had waited long enough for a definitive response from the District and filed a complaint with DPI, charging that the lack of 9th and 10th grade accelerated classes at West violated state educational standards. I imagine the teachers at West most interested in this issue were frustrated as well. An additional complication was that West’s Small Learning Communities grant coordinator, Heather Lott, moved from West to an administrative position in the Doyle building, which couldn’t have helped communication with the West teachers.

The administration finally decided they had developed the Dual Pathways plan sufficiently that they could share it publicly. (Individual School Board members were provided an opportunity to meet individually with Dan Nerad and Pam Nash for a preview of the plan before it was publicly announced, and most of us took advantage of the opportunity.) Last Wednesday, October 13, the administration presented the plan at a meeting of high school department chairs, and described it later in the day at a meeting of the TAG Advisory Committee. On the administration side, the sense was that those meetings went pretty well.

Then came Thursday, and the issue blew up at West. I don’t know how it happened, but some number of teachers were very upset about what they heard about the plan, and somehow or another they started telling students about how awful it was. I would like to learn of a reason why I shouldn’t think that this was appallingly unprofessional behavior on the part of whatever West teachers took it upon themselves to stir up their students on the basis of erroneous and inflammatory information, but I haven’t found such a reason yet.Lots of related links:

- “Stand Up Against the MMSD High School Reform”

- Madison school district to consider alternatives to traditional public schools

- Advanced Placement, Gifted Education & A Hometown Debate

- On the Gifted & Talented Complaint Against the Madison School District

- Madison School District 2010-2011 Enrollment Report, Including Outbound Open Enrollment (3.11%)

- Complaint Filed Against Madison Schools

- English 10

- District Small Learning Community Grant – Examining the Data From Earlier Grants, pt. 2

- Madison United for Academic Excellence has a number of posts on this matter, as does greatmadisonschools.org

An Update on Madison’s Proposed 4K Program

Purpose: The purpose of this Data Retreat is to provide all BOE members with an update on the progress of 4K planning and the work of subcommittees with a recommendation to start 4K September, 2011.

Research Providing four year old kindergarten (4K) may be the district’s next best tool to continue the trend of improving academic achievement for all students and continuing to close the achievement gap.

The quality of care and education that children receive in the early years of their lives is one of the most critical factors in their development. Empirical and anecdotal evidence clearly shows that nurturing environments with appropriate challenging activities have large and lasting effects on our children’s school success, ability to get along with others, and emotional health. Such evidence also indicates that inadequate early childhoOd care and education increases the danger that at-risk children will grow up with problem behaviors that can lead to later crime and violence.

The primary reason for the Madison Metropolitan School District’s implementation of four year old kindergarten (4K) is to better prepare all students for educational success. Similarly, the community and society as a whole receive many positive benefits when students are well prepared for learning at a young age. The Economic Promise of Investing in High-Quality Preschool: Using Early Education to Improve Economic Growth and the Fiscal Sustainability of States and the Nation by The Committee for Economic Development states the following about the importance of early learning.

Failing schools chase reform dollars

As far as failing schools are concerned, Custer High School has been on the watch list for years.

The north side Milwaukee institution on Sherman Blvd. has one of the highest populations of special education students in the district, mostly for behavioral problems. Since 2002, no more than 20% of its 10th-graders have tested proficient or higher in either reading or in math on state tests. Student enrollment has been in a freefall.

As part of President Barack Obama’s push to turn around the worst performing 5% of schools in the country, Custer is in the crosshairs. The government ordered states to identify their lowest performers through a new formula earlier this year and then increased the pot of improvement grant money available to them, provided those schools implement federally approved reforms such as contracting with management companies or replacing principals.

But will those be enough to improve Custer and the other turnaround schools, where previous reform efforts have failed?

Milwaukee Public Schools – where all of Wisconsin’s lowest-performing schools are located – is on its way to finding out. Last week it applied for $45 million in school improvement grants that the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction is authorized to distribute. The application asked for grants worth from $50,000 to $2 million for 47 schools, and the district expects to hear by the end of this week if its plans are approved, Marcia Staum, MPS director of school improvement, said Tuesday.

Madison High School REal Grant Report to the School Board

Madison School District [4.6MB PDF]: