Search Results for: "Will Fitzhugh"

Cross Purposes

Will Fitzhugh

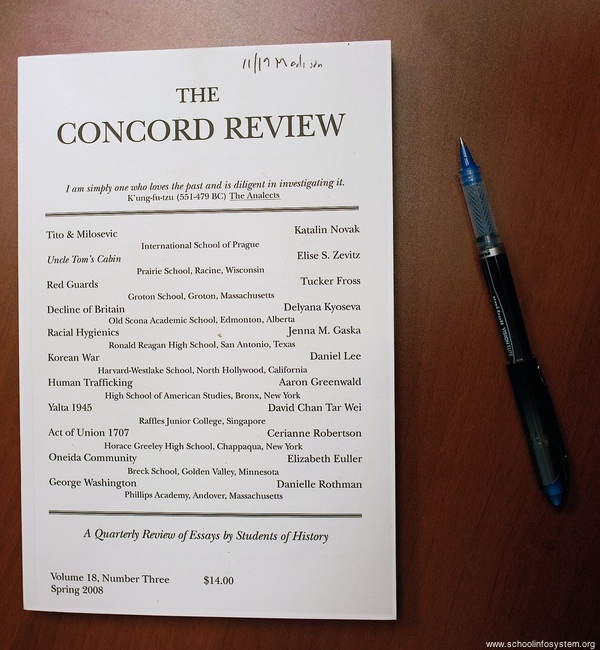

The Concord Review

A recent survey of college professors by the Chronicle of Higher Education found that nearly 90% thought that the students they teach were not very well prepared in reading, doing research and academic writing by their high schools.

At the same time, many college admissions officers ask students for 500-word “personal statements,” which have become known as “college essays,” and many high school English department spend a lot of their writing instruction on this sort of effort.

History departments and English departments are assigning fewer and fewer term papers, so it is not surprising that lots of students are arriving in college not knowing how to do research or write academic papers.

Why is it that college admissions officers and college professors seem to be working at cross purposes when it comes to student writing? College professors want students to be able to write serious research papers when they are assigned in their history, economics, political science, etc., classes, but that is not the message that is going out to high school applicants from the college admissions offices.

Most of the attention, if not all, in the college counseling offices at the secondary level is on what it will take to gain students admission to colleges, not on whether, for example, they have the academic knowledge and skills to graduate from college. That is someone else’s concern. Recently the Gates Foundation has taken up the challenge of trying to find out why students drop out of community colleges in such large numbers.

Read the Whole Book

The Concord Review

22 September 2009

For the last seven or eight years, I have been trying to get funding for a study of the assignment of complete nonfiction (i.e. history) books in U.S. public high schools. No one seems to be interested in such a study, but I have come to believe, from anecdotes and interviews, that the majority of our public high school students now graduate without ever having read a single complete nonfiction book, which would seem to be a handicap for them as they encounter college reading lists in subjects other than literature.

I am told that students in history classes do read excerpts, but those are a pale shadow of the complete work, and they do not discover, unless they read on their own, the difference between an excerpt and the sweep of an entire book.

For example, if high school students hear anything about Harry Truman, they are usually asked to decide whether his decision to drop the atomic bomb was right or wrong.

They miss anything about what he did when he was their age or younger. David McCullough worked on his Pulitzer-Prize-winning Truman for ten years, and here is an excerpt about HST when he was ten:

“For his tenth birthday, in the spring of 1894, his mother presented him with a set of large illustrated volumes grandly titled in gold leaf Great Men and Famous Women. He would later count the moment as one of life’s turning points.” p. 43

and in high school: “He grew dutifully, conspicuously studious, spending long afternoons in the town library, watched over by a white plaster bust of Ben Franklin. Housed in two rooms adjacent to the high school, the library contained perhaps two thousand volumes. Harry and Charlie Ross vowed to read all of them, encyclopedias included, and both later claimed to have succeeded…History became a passion, as he worked his way through a shelf of standard works on ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome…’Reading history, to me, was far more than a romantic adventure. It was solid instruction and wise teaching which I somehow felt I wanted and needed.’ He decided, he said, that men make history, otherwise there would be no history. History did not make the man, he was quite certain.” p. 58

Most of our high school students would have no idea that Harry Truman worked on the small family farm from 1906 to 1914:

“Harry learned to drive an Emerson gang plow, two plows on a three-wheeled frame pulled by four horses. The trick was to see that each horse pulled his part of the load. With an early start, he found, he could do five acres in a ten-hour day”….”Every day was work, never-ending work, and Harry did ‘everything there was to do’–hoeing corn and potatoes in the burning heat of summer, haying, doctoring horses, repairing equipment, sharpening hoes and scythes, mending fences…Harry’s ‘real love’ was the hogs, which he gave such names as ‘Mud,’ ‘Rats,’ and ‘Carrie Nation.’ Harry also kept the books….” pp. 74, 75

Perhaps this time on the farm toughed him for his job as commander of artillery Battery ‘D’ in World War I: “Harry called in the other noncommissioned officers and told them it was up to them to straighten things out. ‘I didn’t come here to get along with you,’ he said. ‘You’ve got to get along with me. And if there of you who can’t, speak up right now, and I’ll bust you right back now.’ There was no mistaking his tone. No one doubted he meant exactly what he said. After that, as Harry remembered, ‘We got along.’ But a private named Floyd Ricketts also remembered the food improving noticeably and that Captain Truman took a personal interest in the men and would talk to them in a way most officers wouldn’t.” pp. 117-118

And in the United States Senate, investigating waste, fraud and abuse: “Its formal title was the Senate Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, but from the start it was spoken of almost exclusively as the Truman Committee…’Looks like I’ll get something done,’ Harry wrote to Bess.”…”His proposal, as even his critics acknowledged, was a masterstroke. He had set himself a task fraught with risk–since inevitably it would lead to conflict with some of the most powerful, willful people in the capital, including the President–but again as in France, as so often in his life, the great thing was to prove equal to the task.” p. 259

All of these quotes are from David McCullough’s Truman, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. The book is 992 pages long and there are some other great ‘excerpts’ in it, of course. My point is to show a bit of how much our high school students might miss in trying to understand the man who made the decision to drop the atomic bomb if they don’t read the whole book. Some will say 992 pages is too much for high school students, who have work and sports and extracurricular activities as well as 5-6 hours a day of electronic entertainment already. I would just argue that if students now can take calculus and chemistry, and in some cases, even Chinese, they ought to be able to spend as much time on a complete nonfiction book as they do at football or basketball practice, even if their reading of a complete book is spread out over several weeks. Reading a complete nonfiction (history) book will not only help to prepare them for college (nonfiction) reading lists, it will also give them a more complete glimpse into one of our Presidents, and after reading, for example, Truman, they should have a better understanding of why someone like David McCullough thought writing it was worth ten years of his life, and why the Pulitzer committee thought it should receive their prize.

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

Literacy in Schools: Writing in Trouble

Surely if we can raise our academic standards for math and science, then, with a little attention and effort, we can restore the importance of literacy in our public high schools. Reading is the path to knowledge and writing is the way to make knowledge one’s own.

Education.com

17 September 2009

by Will Fitzhugh

Source: Education.com Member Contribution

Topics: Writing Conventions

[originally published in the New Mexico Journal of Reading, Spring 2009]

For many years, Lucy Calkins, described once in Education Week as “the Moses of reading and writing in American education” has made her major contributions to the dumbing down of writing in our schools. She once wrote to me that: “I teach writing, I don’t get into content that much.” This dedication to contentless writing has spread, in part through her influence, into thousands and thousands of classrooms, where “personal” writing has been blended with images, photos, and emails to become one of the very most anti-academic and anti-intellectual elements of the education we now offer our children, K-12.

In 2004, the College Board’s National Commission on Writing in the Schools issued a call for more attention to writing in the schools, and it offered an example of the sort of high school writing “that shows how powerfully our students can express their emotions”:

“The time has come to fight back and we are. By supporting our leaders and each other, we are stronger than ever. We will never forget those who died, nor will we forgive those who took them from us.”

Or look at the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the supposed gold standard for evaluating academic achievement in U.S. schools, as measured and reported by the National Center for Education Statistics. In its 2002 writing assessment, in which 77 percent of 12th graders scored “Basic” or “Below Basic,” NAEP scored the following student response “Excellent.” The prompt called for a brief review of a book worth preserving. In a discussion of Herman Hesse’s Demian, in which the main character grows up, the student wrote,“High school is a wonderful time of self-discovery, where teens bond with several groups of friends, try different foods, fashions, classes and experiences, both good and bad. The end result in May of senior year is a mature and confident adult, ready to enter the next stage of life.”

It is obvious that this “Excellent” high school writer is expressing more of his views on his own high school experience than on anything Herman Hesse might have had in mind, but that still allows this American student writer to score very high on the NAEP assessment of writing.

This year, the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) has released a breakthrough report on writing called “Writing in the 21st Century,” which informs us, among other things, that:

High School Research Paper Lightens Up

“The more students are able to do in research and writing in high school, the more they’ve got a nice leg up.”

At the mere mention of research papers, Kelly Cronin’s usually highly motivated Summit Country Day Upper School students turn listless. Some groan. The Hyde Park Catholic school requires all high school students to write lengthy research papers each year on history, religion or literature.

Cronin’s sophomores write history papers. They pick a topic in late September and by May they’ll have visited libraries, pawed through card catalogs, and plumbed non-fiction books and scholarly articles.

They’ll turn in 200 or so index cards of notes. They’ll write and revise about 15 pages.

Cronin gladly grades 35 or more papers with such titles as “The Role of the Catholic Church in European Witchcraft Trials” and “Star Trek Reflected in President Johnson’s Great Society.”

“It’s time-consuming,” she says. “It takes over your life. But I’m not married, and I don’t have any kids.”

But most high school teachers aren’t like Cronin and most schools aren’t like Summit. At many high schools across the country, the in-depth research paper is dying or dead, education experts say, victims of testing and time constraints.

Juniors and seniors still get English papers, says Anne Flick, a specialist in gifted education in Springfield Township. “But in my day, that was 15 or 20 pages. Nowadays, it’s five.”

High school teachers, averaging 150 to 180 students, can’t take an hour to grade each long paper, Cronin said.

The assignment may not be necessary, says Tiffany Coy, an assistant principal at Oak Hills High in Bridgetown. “Research tells you it’s not necessarily the length; it’s the skills you develop,” she said.

But some educators disagree.

“Students come to college with no experience in writing papers, to the continual frustration of their professors,” said William Fitzhugh, a former high school teacher who publishes The Concord Review, a quarterly in Massachusetts that selects and publishes some of the nation’s best high school papers. [from 36 countries so far]

“If we want students to be able to read and understand college books and to write research papers there, then we must give students a chance to learn how to do that in a rigorous college preparatory program. That is not happening,” he said.

Teachers see the problem. Fitzhugh’s organization commissioned a national study of 400 randomly selected high school teachers in 2002 that showed:

-95% believe research papers, especially history papers, are important.

-62% said they no longer assign even 12-page papers.

-81% never assign 5,000-word or more papers.

Cold Prospects

The Concord Review

13 August 2009

Today’s Boston Globe has a good-sized article on “Hot Prospects,”–local high school football players facing “increasing pressure from recruiters to make their college decisions early.”

That’s right, it is not the colleges that are getting pressure from outstanding students seeking admission based on their academic achievement, it is colleges putting pressure on high school athletes to get them to “sign” with the college.

The colleges are required by the AAU to wait until the prospect is a Senior in high school before engaging in active recruiting including “visits and contact from college coaches,” and, for some local football players the recruiting pressure even comes from such universities as Harvard and Stanford.

Perhaps Senior year officially starts in June, because the Globe reports that one high school tight end from Wellesley, Massachusetts, for example, “committed to Stanford in early June, ending the suspense of the region’s top player.”

The University of Connecticut “made an offer to” an athletic quarterback from Natick High School, “and a host of others, including Harvard and Stanford, are interested,” says the Globe.

In the meantime, high school football players are clearly not being recruited by college professors for their outstanding academic work. When it comes to academic achievement, high school students have to apply to colleges and wait until the college decides whether they will be admitted or not. Some students apply for “Early Decision,” but in that case, it is the college, not the athlete, who makes the decision to “commit.”

Intelligent and diligent high school students who manage achievement in academics even at the high level of accomplishment of their football-playing peers who are being contacted, visited, and recruited by college coaches, do not find that they are contacted, visited, or recruited by college professors, no matter how outstanding their high school academic work may be.

In some other countries, the respect for academic work is somewhat different. One student, who earned the International Baccalaureate Diploma and had his 15,000-word independent study essay on the Soviet-Afghan War published in The Concord Review last year, was accepted to Christ Church College, Oxford, from high school. He reported to me that during the interview he had with tutors from that college, “they spent a lot of time talking to me about my TCR essay in the interview.” He went on to say: “Oxford doesn’t recognize or consider extra-curriculars/sports in the admissions process (no rowing recruits) because they are so focused on academics. So I thought it was pretty high praise of the Review that they were so interested in my essay (at that time it had not won the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize).”

There are many other examples from other countries of the emphasis placed on academic achievement and the lack of emphasis on sports and other non-academic activities, perhaps especially in Asian countries.

One young lady, a student at Boston Latin School, back from a Junior year abroad at a high school in Beijing, reported in the Boston Globe that: “Chinese students, especially those in large cities or prosperous suburbs and counties and even some in impoverished rural areas, have a more rigorous curriculum than any American student, whether at Charlestown High, Boston Latin, or Exeter. These students work under pressure greater than the vast majority of U.S. students could imagine…teachers encourage outside reading of histories rather than fiction.”

That is not to say that American (and foreign) high school students who do the work to get their history research papers published in The Concord Review don’t get into colleges. So far, ninety have gone to Harvard, seventy-four to Yale, twelve to Oxford, and so on, but the point is that, unlike their football-paying peers, they are not contacted, visited and recruited in the same way.

The bottom line is that American colleges and universities, from their need to have competitive sports teams, are sending the message to all of our high school students (and their teachers) that, while academic achievement may help students get into college one day, what colleges are really interested in, and willing to contact them about, and visit them about, and take them for college visits about, and recruit them for, is their athletic achievement, not their academic achievement. What a stupid, self-defeating message to keep sending to our academically diligent secondary students (and their diligent teachers)!!

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

TEENAGE SOAPBOX

Will Fitzhugh, The Concord Review

30 July 2009

Little Jack Horner sat in the corner

Eating his Christmas pie:

He stuck in his thumb, and pulled out a plum

And said, “What a good boy am I!”

I publish history research papers by secondary students from around the world, and from time to time I get a paper submitted which includes quite a bit more opinion than historical research.

The other day I got a call from a prospective teenage author saying he had noticed on my website that most of the papers seemed to be history rather than opinion, and was it alright for him to submit a paper with his opinions?

I said that opinions were fine, if they were preceded and supported by a good deal of historical research for the paper, and that seemed to satisfy him. I don’t know if he will send in his paper or not, but I feel sure that like so many of our teenagers, he has received a good deal of support from his teachers for expressing his opinions, whether very well-informed or not.

From John Dewey forward, many Progressive educators seem to want our students to “step away from those school books, and no one gets hurt,” as long as they go out and get involved in the community and come back to express themselves with plenty of opinions on all the major social issues of the world today.

This sort of know-nothing policy-making was much encouraged in the 1960s in the United States, among the American Red Guards at least. In China, there was more emphasis on direct action to destroy the “Four Olds” and beat up and kill doctors, professors, teachers, and anyone else with an education. Mao had already done their theorizing for them and all they had to do was the violence.

Over here, however, from the Port Huron Statement to many other Youth Manifestos, it was considered important for college students evading the draft to announce their views on society at some length. Many years after the fact, it is interesting to note, as Diana West wrote about their philosophical posturing in The Death of the Grown-Up:

“What was it all about? New Left leader Todd Gitlin found such questions perplexing as far back as the mid-1960s, when he was asked ‘to write a statement of purpose for a New Republic series called ‘Thoughts of Young Radicals.’ In his 1978 memoir, The Sixties, Gitlin wrote: ‘I agonized for weeks about what it was, in fact, I wanted.’ This is a startling admission. Shouldn’t he have thought about all this before? He continued: “The movement’s all-purpose answer to ‘What do you want?’ and ‘How do you intend to get it?’ was: ‘Build the movement.’ By contrast, much of the counterculture’s appeal was its earthy answer: ‘We want to live like this, voila!'”

For those of the Paleo New Left who indulged in these essentially thoughtless protests, the Sixties are over, but for many students now in our social studies classrooms, their teachers still seem to want them to Stand Up on the Soapbox and be Counted, to voice their opinions on all sorts of matters about which they know almost nothing.

I have published research papers by high school students who have objected to eugenics, racism, China’s actions in Tibet, gender discrimination, and more. But I believe in each case such opinions came at the end of a fairly serious history research paper full of information and history the student author had taken the trouble to learn.

When I get teenage papers advising Secretary Clinton on how to deal with North Korea, or Timothy Geitner and Ben Bernanke on how to help the U.S. economy correct itself, or telling the President what to do about energy, if these papers substitute opinion for research into these exceedingly complex and difficult problems, I tend not to publish them.

My preference is for students to “step away from that soapbox and no one gets hurt,” that is, to encourage them, in their teen years, to read as many nonfiction books as they can, to learn how little they understand about the problems of the past and present, and to defer their pronouncements on easy solutions to them until they really know what they are talking about and have learned at least something about the mysterious workings of unintended consequences, just for a start.

Since 1987, I have published more than 860 exemplary history research papers by secondary students from 36 countries (see www.tcr.org for examples), and I admire them for their work, but the ones I like best have had some well-earned modesty to go along with their serious scholarship.

Peer Pressure

Will Fitzhugh

The Concord Review

6 July 2009

We make frequent use of the influence of their high school peers on many of our students. We have peer counseling programs and even peer discipline systems, in some cases. We show students the artistic abilities of their peers in exhibitions, concerts, plays, recitals, and the like.

Most obviously, we put before our high school students the athletic skills and performances of their peers in a very wide range of meets, matches, and games, some of which, of course, are better attended than others.

While some high schools still have just one valedictorian, fellow students have little or no idea what sort of academic work the student who is first in her class has done. Academic scholarships may be announced, but it is quite impossible for peers to see the academic work for which the scholarship has been awarded. Here again, the contrast with athletics is clear.

We show high school students the artistic, athletic, and other examples of the outstanding efforts and accomplishments of their peers without seeming to worry that such examples will send their peers into unmanageable depressions or cause them to give up their own efforts to do their best.

When it comes to academic achievements, on the other hand, we do seem to worry that they will have a harmful effect if they are shown to other students. I am not quite sure how that attitude got its hold on us, but I do have some comments from authors whose papers I have published, on their reaction to seeing the exemplary academic work of their peers:

“When a former history teacher first lent me a copy of The Concord Review, I was inspired by the careful scholarship crafted by other young people. Although I have always loved history passionately, I was used to writing history papers that were essentially glorified book reports…As I began to research the Ladies’ Land League, I looked to The Concord Review for guidance on how to approach my task…In short, I would like to thank you not only for publishing my essay, but for motivating me to develop a deeper understanding of history. I hope that The Concord Review will continue to fascinate, challenge and inspire young historians for years to come.”

North Central High School (IN) Class of 2005

“The opportunity that The Concord Review presented drove me to rewrite and revise my paper to emulate its high standards. Your journal truly provides an extraordinary opportunity and positive motivation for high school students to undertake extensive research and academic writing, experiences that ease the transition from high school to college.”

Thomas Worthington High School (OH) Class of 2008

“Thank you for selecting my essay regarding Augustus Caesar and his rule of the Roman Republic for publication in the Spring 2009 issue of The Concord Review. I am both delighted and honored to know that this essay will be of some use to readers around the world. The process of researching and writing this paper for my IB Diploma was truly enjoyable and it is my hope that it will inspire other students to undertake their own research projects on historical topics.”

Old Scona Academic High School, Edmonton, Alberta, (Canada) Class of 2008

“In the end, working on that history paper, inspired by the high standard set by The Concord Review, reinvigorated my interest not only in history, but also in writing, reading and the rest of the humanities. I am now more confident in my writing ability, and I do not shy from difficult academic challenges. My academic and intellectual life was truly altered by my experience with that paper, and the Review played no small role! Without the Review, I would not have put so much work into the paper. I would not have had the heart to revise so thoroughly.”

Isidore Newman School (LA) Class of 2003

“At CRLHS, a much-beloved history teacher suggested to me that I consider writing for The Concord Review, a publication that I had previously heard of, but knew little about. He proposed, and I agreed, that it would be an opportunity for me to pursue more independent work, something that I longed for, and hone my writing and research skills in a project of considerably broader scope than anything I had undertaken up to that point.”

Cambridge Rindge and Latin High School (MA) Class of 2003

Now, whenever a counterintuitive result–like this enthusiasm for a challenge–is found, there is always an attempt to limit the damage to our preconceptions. “This is only a tiny fringe group (of trouble-makers, nerds, etc.)” or “most of our high school students would not respond with interest to the exemplary academic work of their peers.” The problem with those arguments is that we really don’t know enough. We haven’t actually tried to see what would happen if we presented our high school students with good academic work done by their more diligent peers. Perhaps we should consider giving that experiment a serious try. I have, as it happens, some good high school academic work to use as examples in such a trial…

Critical Likability

Will Fitzhugh

The Concord Review

28 June 2009

As we approach the end of the first decade of the first century of the third millennium of the Christian Era, the corporate members of the new and influential Partnership for 21st Century Skills have begun to look beyond and behind and beneath their earlier commitment to the education of our students in critical thinking, collaborative problem solving, and global awareness.

It has become obvious to industry leaders that more fundamental than all these new student skills for success in the business world is really Critical Likability. While it may be useful for new employees to know that the world is round, and that solving problems is sometimes easier if others provide help, and that real thinking is superior to not thinking at all, these all pale in importance to whether other people like you or not.

Being a great communicator is important, and reading and writing have received some support from the 21st Century leaders, but those are not of much value if no one likes you and no one wants to hear what you have to say, whether oral or written.

Critical Likability, it must be understood, goes far beyond mere popularity in school, although they share some essential tools and characteristics. Future employees must learn, while they are in school, the basic lessons of smiling, personal hygiene (including the control of bad breath and the release of hydrogen sulfide gas), grooming, table manners, the correct handshake, and at least the basics of dressing for success.

At a more advanced level students should be taught to listen, empathize, seem to agree, laugh, hug (only where clearly appropriate), tell jokes, drink (where and when culturally appropriate), play a social sport (like golf), and generally to be likable in the most efficient and effective senses of that word.

A Semantic Hijacking”

Charles J. Sykes, Dumbing Down Our Kids

New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995, pp. 245-247Ironically, “outcomes” were first raised to prominence by leaders of the conservative educational reform movement of the 1980s. Championed by Chester E. Finn, Jr. among others, reformers argued that the obsession with inputs (dollars spent, books bought, staff hired) focused on the wrong end of the educational pipeline. Reformers insisted that schools could be made more effective and accountable by shifting emphasis to outcomes (what children actually learned). Finn’s emphasis on outcomes was designed explicitly to make schools more accountable by creating specific and verifiable educational objectives in subjects like math, science, history, geography, and English. In retrospect, the intellectual debate over accountability was won by the conservatives. Indeed, conservatives were so successful in advancing their case that the term “outcomes” has become a virtually irresistible tool for academic reform.

The irony is that, in practice, the educational philosophies known as Outcome Based Education have little if anything in common with those original goals. To the contrary, OBE–with its hostility to competition, traditional measures of progress, and to academic disciplines in general–can more accurately be described as part of a counterreformation, a reaction against those attempts to make schools more accountable and effective. The OBE being sold to schools represents, in effect, a semantic hijacking.

“The conservative education reform of the 1980s wanted to focus on outcomes (i.e. knowledge gained) instead of inputs (i.e. dollars spent),” notes former Education Secretary William Bennett. “The aim was to ensure greater accountability. What the education establishment has done is to appropriate the term but change the intent.” [emphasis added] Central to this semantic hijacking is OBE’s shift of outcomes from cognitive knowledge to goals centering on values, beliefs, attitudes, and feelings. As an example of a rigorous cognitive outcome (the sort the original reformers had in mind), Bennett cites the Advanced Placement Examinations, which give students credit for courses based on their knowledge and proficiency in a subject area, rather than on their accumulated “seat-time” in a classroom.

In contrast, OBE programs are less interested in whether students know the origins of the Civil War or the author of The Tempest than whether students have met such outcomes as “establishing priorities to balance multiple life roles” (a goal in Pennsylvania) or “positive self-concept” (a goal in Kentucky). Where the original reformers aimed at accountability, OBE makes it difficult if not impossible to objectively measure and compare educational progress. In large part, this is because instead of clearly stated, verifiable outcomes, OBE goals are often diffuse, fuzzy, and ill-defined–loaded with educationist jargon like “holistic learning,” “whole-child development,” and “interpersonal competencies.”

Where original reformers emphasized schools that work, OBE is experimental. Despite the enthusiasm of educationists and policymakers for OBE, researchers from the University of Minnesota concluded that “research documenting its effects is fairly rare.” At the state level, it was difficult to find any documentation of whether OBE worked or not and the information that was available was largely subjective. Professor Jean King of the University of Minnesota’s College of Education describes support for the implementation of OBE as being “almost like a religion–that you believe in this and if you believe in it hard enough, it will be true.” And finally, where the original reformers saw an emphasis on outcomes as a way to return to educational basics, OBE has become, in Bennett’s words, “a Trojan Horse for social engineering, an elementary and secondary school version of the kind of ‘politically correct’ thinking that has infected our colleges and universities.”

=============

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

Rigid Athletic Tracking

The New York Times reports that the Stamford, Connecticut public schools may finally achieve the goal of eliminating academic tracking, putting students of mixed academic ability in the same classes at last. The Times reports that “this 15,000-student district just outside New York City…is among the last bastions of rigid educational tracking more than a decade after most school districts abandoned the practice.”

If that newspaper thinks Stamford has taken too long to get rid of academic tracks for K-12 students, how would they report on the complete dominance of athletic tracking in schools all over the country? Not only does such athletic tracking take place in all our schools, but there is, at present, no real movement to eliminate it, unbelievable as that may seem.

Athletes in our school sports programs are routinely tracked into groups of students with similar ability, presumably to make their success in various sports matches, games, and contests more likely. But so far no attention is paid to the damage to the self-esteem of those student athletes whose lack of ability and coordination doom them to the lower athletic tracks, and even, in many cases, may deprive them of membership on school teams altogether.

It is also an open secret that many of our school athletic teams ignore diversity entirely, and make no effort to be sure that, for example, Asians and Caucasians are included, in proportion to their numbers in the general population, in football, basketball, and track teams. Athletic ability and success are allowed to overwhelm other important measures, and this must be taken into account in any serious Athletic Untracking effort.

In Stamford, some parents are opposed to the elimination of academic tracking, and have threatened to enroll their children in private schools. This problem would no doubt also arise in any serious Athletic Untracking program which could be introduced. Parents who spend money on private coaches for their children would not stand by and see the playing time of their young athletes cut back or even lost by any program to make all school sports teams composed of mixed-ability athletes.

The New York Times reports that “Deborah Kasak, executive director of the National Forum to Accelerate Middle Grades Reform, said research is showing that all students benefit from mixed-ability classes.”

Perhaps it will be argued that all athletes benefit from mixed-ability teams as well, but many would predict not only plenty of losing seasons for any schools which eliminate Athletic Tracking programs, but also very poor scholarship prospects for the best athletes who are involved in them. Just as students who are capable of excellent academic work are often sacrificed to the dream of an academic (Woebegone) world in which all are equal, so student athletes will find their skills and performance severely degraded by any Athletic Untracking program.

Nevertheless, when educators are more committed to diversity and equality of outcomes in classrooms than they are in academic achievement, they have eliminated academic tracking and set up mixed-ability classrooms.

Surely athletic directors and coaches can be made to see the supreme importance of some new diversity and equity initiatives as well, and persuaded, at the risk of losing their jobs, to develop and provide non-tracked athletic programs for our mixed-ability student athletes. After all, winning games may be fun, but, in the long run, people can be led to realize that being politically correct is much more worthwhile than real achievement in any endeavor in our public schools. As the Dean of a major School of Education recently informed me: “The myth of individual greatness is a myth.” [sic] The time for the elimination of Athletic Tracking has now arrived!

15 June 2009

Will Fitzhugh

The Concord Review

Summer Fun

June means the end of high school and the start of summer. Perhaps there will be jobs or other chores, but, as James Russell Lowell wrote in The Vision of Sir Launfal, “what is so rare as a day in June? Then, if ever, come perfect days…”

Those rare June days are full of mild air, sunshine, leisure, and time, at last, for student to pick up that absorbing nonfiction book for which there has been no place in their high school curriculum.

Why is it that so many, if not most, of our high school graduates arrive in college without ever having read a single complete nonfiction book in high school, so that when they confront their college reading lists, full of such books, they are somewhat at sea?

The main reason is that the English department controls reading in most schools, and for most of them the only reading of interest is fiction, so that is all that students are asked to read.

For the boys, and now the girls too, who may soon serve in the military, and are interested in military history, they have to read the military history books they will enjoy on their own, after school or, better, in the summer. All the students who would love history books on any topic would do well to pick them up in the summer, when their other assignments, of fiction books and the like, cannot interfere.

The story of the world’s work and the issues that trouble the world now (and in the past) can only be found in nonfiction books, and for students who can see the time coming when they will be responsible for the work of the world, those are the books which they should read, and have time to read, mainly in the summer months.

Summer reading of nonfiction books also means that when they return to their history, economics, sociology, and even their science and English classes in the fall, they will bring a more substantial and more nuanced understanding of the world they will be studying, with the benefit of the knowledge and appreciation they have gained in their nonfiction reading over the summer.

For those who are concerned with “Summer Loss”–the observed decline in student knowledge and skill over the summer months–the reading of nonfiction books brings a double benefit. The habit and the skill of reading significant material are refreshed and reinforced in that way, and knowledge is gained rather than drained away over the summer. And in addition, engagement with serious topics confirms young people in their primary role as students rather than “just kids” as they read over the summer.

Adults still buy and read a lot of nonfiction books, even in these days of the Internet/Web and Television, and students will have a much better chance of taking part in adult conversations over the summer if they are reading books too.

The objection will surely be raised in some quarters that reading nonfiction books in the summer is too much like work. One answer that could be offered is that, as reported in Diploma to Nowhere, more than a million of our high school graduates every year, who are accepted at colleges, are required to take remedial courses because they have not worked hard enough to be ready for regular courses. The problem then may actually be that our high schools are too much fun and not enough work and we give our diplomas to far too many “fools” as a result.

Malcolm Gladwell, in Outliers, cites K. Anders Ericsson’s research on the difference between amateur and professional pianists, and writes: “Their research suggests that once a musician has enough ability to get into a top musical school, the thing that distinguishes one performer from another is how hard he or she works. That’s it. And what’s more, the people at the very top don’t just work harder or even much harder than everyone else. They work much, much harder.”

We see those who labor constantly to relieve our students from working too hard academically. They worry about stress, strain, overwork, joyless lives, etc. But that only seems to apply to academics. When it comes to sports, there is nearly universal satisfaction with young athletes who dedicate themselves to their fitness and the skills needed for their sport(s) not only after school, but during the summer as well.

While reading nonfiction books in the summer has not yet been widely accepted or required, high school athletes are expected to run, lift weights, stretch, and shoot hoops (or whatever it takes for their sports) as often in the summer as they can find the time. Perhaps if we applied the seriousness with which we take sports for young people to their pursuit of academic achievement, we would find more students reading complete nonfiction books in the summer and fewer needing remedial courses later.

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

Report From China: “Novels are not taught in class, and teachers encourage outside reading of histories rather than fiction.”

Annie Osborn in the Boston Globe:

Teen’s lessons from China. I am a product of an American private elementary school and public high school, and I am accustomed to classrooms so boisterous that it can be considered an accomplishment for a teacher to make it through a 45-minute class period without handing out a misdemeanor mark. It’s no wonder that the atmosphere at Yanqing No. 1 Middle School (“middle school” is the translation of the Chinese term for high school), for students in grades 10-12, seems stifling to me. Discipline problems are virtually nonexistent, and punishments like lowered test scores are better deterrents for rule breaking than detentions you can sleep through.

But what does surprise me is that, despite the barely controlled chaos that simmers just below the surface during my classes at Boston Latin School, I feel as though I have learned much, much more under the tutelage of Latin’s teachers than I ever could at a place like Yanqing Middle School, which is located in a suburb of Beijing called Yanqing.

Students spend their days memorizing and doing individual, silent written drills or oral drills in total unison. Their entire education is geared toward memorizing every single bit of information that could possibly materialize on, first, their high school entrance exams, and next, their college entrance exams. This makes sense, because admission to public high schools and universities in China is based entirely on test scores (although very occasionally a rich family can buy an admission spot for their child), and competition in the world’s most populous country to go to the top schools makes the American East Coast’s Harvard-or-die mentality look puny.

Chinese students, especially those in large cities or prosperous suburbs and counties and even some in impoverished rural areas, have a more rigorous curriculum than any American student, whether at Charlestown High, Boston Latin, or Exeter. These students work under pressure greater than the vast majority of US students could imagine.

It’s Not About You

3 June 2009

Will Fitzhugh

The Concord Review

Although many high school students do realize it, they all should be helped to understand that their education is not all about them, their feelings, their life experiences, their original ideas, their hopes, their goals, their friends, and so on.

While it is clear that Chemistry, Physics, Chinese, and Calculus are not about them, when it comes to history and literature, the line is more blurred. And as long as many writing contests and college admissions officers want to hear more about their personal lives, too many students will make the mistake of assuming the most important things for them to learn and talk about in their youth are “Me, Myself, and Me.”

Promoters of Young Adult Fiction seem to want to persuade our students that the books they should read, if not directly about their own lives, are at least about the lives of people their own age, with problems and preoccupations like theirs. Why should they read War and Peace or Middlemarch or Pride and Prejudice when they have never been to Russia or England? Why should they read Battle Cry of Freedom when the American Civil War probably happened years before they were even born? Why should they read Miracle at Philadelphia when there is no love interest, or The Path Between the Seas when they are probably not that interested in construction projects at the moment?

Almost universally, college admissions officers ask not to see an applicant’s most serious Extended Essay or history research paper, to give an indication of their academic prowess, but rather they want to read a “personal essay” about the applicant’s home and personal life (in 500 words or less).

Teen Magazines like Teen Voices and Teen People also celebrate Teen Life in a sadly solipsistic way, as though teens could hardly be expected to take an interest in the world around them, and its history, even though before too long they will be responsible for it.

Even the most Senior gifted program in the United States, the Johns Hopkins Center for Talented Youth, which finds some of the most academically promising young people we have, and offers them challenging programs in Physics, Math, and the like, when it comes to writing, it asks them to compose “Creative Nonfiction” about the events and emotions of their daily lives, if you can believe that.

The saddest thing, to me, is that I know young people really do want to grow up, and to learn a lot about their inheritance and the world around them, and they do look forward to developing the competence to allow them to shoulder the work of the world and give it their best effort.

So why do we insist on infantilizing them with this incessant effort to turn their interests back in on themselves? Partly the cause is the enormous, multi-billion-dollar Teen market, which requires them to stay focused on themselves, their looks, their gear, their friends and their little shrunken community of Teen Life. If teens were encouraged to pursue their natural desires to grow up, what would happen to the Teen Market? Disaster.

In addition, too many teachers are afraid to help their students confront the pressure to be self-involved, and to allow them to face the challenges of preparing for the adult world. Some teachers, themselves, are more comfortable in the Teen World than they think they would be “out there” in the Adult World, and that inclines them to blunt the challenges they could offer to their students, most of whom will indeed seek an opportunity to venture into that out-of-school world themselves.

We all tend to try to influence those we teach to be like us, and if we are careful students and diligent thinkers as teachers, that is not all bad. But we surely should neither want nor expect all our students to become schoolteachers working with young people. We should keep that in mind and be willing to encourage our students to engage with the “Best that has been said and thought,” to help them prepare themselves for the adulthood they will very soon achieve.

For those who love students, it is always hard to see them walk out the door at the end of the school year, and also hard when they don’t even say goodbye. But we must remember that for them, they are not leaving us, so much as arriving eagerly into the world beyond the classroom, and while we have them with us, we should keep that goal of theirs in mind, and refuse to join with those who, for whatever reason, want to keep our young people immature, and thinking mostly about themselves, for as long as possible.

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

Horace Mann High School

Imagine that somewhere in the United States there is a Horace Mann (American educator)“>Horace Mann High School, with a student who is a first-rate softball pitcher. Let us further imagine that although she set a new record for strikeouts for the school and the district, she was never written up in the local paper. Let us suppose that even when she broke the state record for batters retired she received no recognition from the major newspapers or other media in the state.

Imagine a high school boy who had broken the high jump record for his school, district, and state, who also never saw his picture or any story about his achievement in the media. He also would not hear from any college track coaches with a desire to interest him in becoming part of their programs.

In this improbable scenario, we could suppose that the coaches of these and other fine athletes at the high school level would never hear anything from their college counterparts, and would not be able to motivate their charges with the possibility of college scholarships if they did particularly well in their respective sports.

These fine athletes could still apply to colleges and, if their academic records, test scores, personal essays, grades, and applications were sufficiently impressive, they might be accepted at the college of their choice, but, of course they would receive no special welcome as a result of their outstanding performance on the high school athletic fields.

This is all fiction, of course, in our country at present. Outstanding athletes do receive letters from interested colleges, and even visits from coaches if they are good enough, and it is then up to the athlete to decide which college sports program they will “commit to” or “sign with,” as the process is actually described in the media. Full scholarships are often available to the best high school athletes, so that they may contribute to their college teams without worrying about paying for tuition or accumulating student debt.

In turn, high school coaches with very good athletes in fact do receive attention from college coaches, who keep in touch to find out the statistics on their most promising athletes, and to get recommendations for which ones are most worth pursuing and most worth offering scholarships to.

These high school coaches are an important agent in helping their promising athletes decide who to “commit to” or who to “sign with” when they are making their higher education plans.

On the other hand, if high school teachers have outstanding students of history, there are no scholarships available for them, no media recognition, and certainly no interest from college professors of history. For their work in identifying and nurturing the most diligent, the brightest, and the highest-achieving students of history, these academic coaches (teachers) are essentially ignored.

Those high school students of history, no matter whether they write first-class 15,000-word history research papers, like Colin Rhys Hill of Atlanta, Georgia (published in the Fall 2008 issue of The Concord Review), or a first-class 13,000-word history research paper, like Amalia Skilton of Tempe, Arizona (published in the Spring 2009 issue of The Concord Review), they will hear from no one offering them a full college scholarship for their outstanding high school academic work in history.

College professors of history will not write or call them, and they will not visit their homes to try to persuade them to “commit to” or “sign with” a particular college or university. The local media will ignore their academic achievements, because they limit their high school coverage to the athletes.

To anyone who believes the primary mission of the high schools is academic, and who pays their taxes mainly to promote that mission, this bizarre imbalance in the mechanics of recognition and support may seem strange, if they stop to think about it. But this is our culture when it comes to promoting academic achievement at the high school level. If we would like to see higher levels of academic achievement by our high school students, just as we like to see higher levels of athletic achievement by our students at the high school level, perhaps we might give some thought to changing this culture (soon).

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

Writing in Trouble

For many years, Lucy Calkins, described once in Education Week as “the Moses of reading and writing in American education” has made her major contributions to the dumbing down of writing in our schools. She once wrote to me that: “I teach writing, I don’t get into content that much.” This dedication to contentless writing has spread, in part through her influence, into thousands and thousands of classrooms, where “personal” writing has been blended with images, photos, and emails to become one of the very most anti-academic and anti-intellectual elements of the education we now offer our children, K-12.

In 2004, the College Board’s National Commission on Writing in the Schools issued a call for more attention to writing in the schools, and it offered an example of the sort of high school writing “that shows how powerfully our students can express their emotions“:

“The time has come to fight back and we are. By supporting our leaders and each other, we are stronger than ever. We will never forget those who died, nor will we forgive those who took them from us.”

Or look at the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), the supposed gold standard for evaluating academic achievement in U.S. schools, as measured and reported by the National Center for Education Statistics. In its 2002 writing assessment, in which 77 percent of 12th graders scored “Basic” or “Below Basic,” NAEP scored the following student response “Excellent.” The prompt called for a brief review of a book worth preserving. In a discussion of Herman Hesse’s Demian, in which the main character grows up, the student wrote,

“High school is a wonderful time of self-discovery, where teens bond with several groups of friends, try different foods, fashions, classes and experiences, both good and bad. The end result in May of senior year is a mature and confident adult, ready to enter the next stage of life.”

Muscular Mediocrity

It is excusable for people to think of Mediocrity as too little of something, or a weak approximation of what would be best, and this is not entirely wrong. However, in education circles, it is important to remember, Mediocrity is the Strong Force, as the physicists would say, not the Weak Force.

For most of the 20th century, as Diane Ravitch reports in her excellent history, Left Back, Americans achieved remarkably high levels of Mediocrity in education, making sure that our students do not know too much and cannot read and write very well, so that even of those who have gone on to college, between 50% and 75% never received any sort of degree.

In the 21st century, there is a new push to offer global awareness, critical thinking, and collaborative problem solving to our students, as a way of getting them away from reading nonfiction books and writing any sort of serious research paper, and that effort, so similar to several of the recurring anti-academic and anti-intellectual programs of the prior century, will also help to preserve the Mediocrity we have so painstakingly forged in our schools.

Research generally has discovered that while Americans acknowledge there may be Mediocrity in our education generally, they feel that their own children’s schools are good. It should be understood that this is in part the result of a very systematic and deliberate campaign of disinformation by educrats. When I was teaching in the high school in Concord, Massachusetts, the superintendent at the time met with the teachers at the start of the year and told us that we were the best high school faculty in the country. That sounds nice, but what evidence did he have? Was there a study of the quality of high school faculties around the country? No, it was just public relations.

The “Lake Woebegone” effect, so widely found in our education system, is the result of parents continually being “informed” that their schools are the best in the country. I remember meeting with an old friend in Tucson once, who informed that “Tucson High School is one of the ten best in the country.” How did she know that? What was the evidence for that claim at the time? None.

Mediocrity and its adherents have really done a first-class job of leading people to believe that all is well with our high schools. After all, when parents ask their own children about their high school, the students usually say they like it, meaning, in most cases, that they enjoy being with their friends there, and are not too bothered by a demanding academic curriculum.

With No Child Left Behind, there has been a large effort to discover and report information about the actual academic performance of students in our schools, but the defenders of Mediocrity have been as active, and almost as successful, as they have ever been in preserving a false image of the academic quality of our schools. They have established state standards that, except in Massachusetts and a couple of other states, are designed to show that all the students are “above the national average” in reading and math, even though they are not.

It is important for anyone serious about raising academic standards in our schools to remember that Mediocrity is the Hundred-Eyed Argus who never sleeps, and never relaxes its relentless diligence in opposition to academic quality for our schools and educational achievement for our students.

There is a long list of outside helpers, from Walter Annenberg to the Gates Foundation, who have ventured into American education with the idea that it makes sense that educators would support higher standards and better education for our students. Certainly that is what they hear from educators. But when the money is allocated and the “reform” is begun, the Mediocrity Special Forces move into action, making sure that very little happens, and that the money, even billions of dollars, disappears into the Great Lake of Mediocrity with barely a ripple, so that no good effect is ever seen.

If this seems unduly pessimistic, notice that a recent survey of college professors conducted by the Chronicle of Higher Education found that 90% of them reported that the students who came to them were not very well prepared, for example, in reading, doing research, and writing, and that the Diploma to Nowhere report from the Strong American Schools program last summer said that more than 1,000,000 of our high school graduates are now placed in remedial courses when they arrive at the colleges to which they have been “admitted.” It seems clear that without Muscular Mediocrity in our schools, we could never have hoped to achieve such a shameful set of academic results.

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

19th Century Skills

13 April 2009

John Robert Wooden, the revered UCLA basketball coach, used to tell his players: “If you fail to prepare, you are preparing to fail.” According to the Diploma to Nowhere report last summer from the Strong American Schools project, more than one million of our high school graduates are in remedial courses at college every year. Evidently we failed to prepare them to meet higher education’s academic expectations.

The 21st Century Skills movement celebrates computer literacy as one remedy for this failing. Now, I love my Macintosh, and I have typeset the first seventy-seven issues of The Concord Review on the computer, but I still have to read and understand each essay, and to proofread eleven papers in each issue twice, line by line, and the computer is no help at all with that. The new Kindle (2) from Amazon is able to read books to you–great technology!–but it cannot tell you anything about what they mean.

In my view, the 19th (and prior) Century Skills of reading and writing are still a job for human beings, with little help from technology. Computers can check your grammar, and take a look at your spelling, but they can’t read for you and they can’t think for you, and they really cannot take the tasks of academic reading and writing off the shoulders of the students in our schools.

There appears to be a philosophical gap between those who, in their desire to make our schools more accountable, focus on the acquisition and testing of academic knowledge and skills in basic reading and math, on the one hand, and those who, from talking to business people, now argue that this is not enough. This latter group is now calling for 21st Century critical thinking, communication skills, collaborative problem solving, and global awareness.

Adolescent Literacy Flim-Flam

The Concord Review

3 April 2009

There is no question that lots of people around the nation are concerned about the literacy of American adolescents. They must be worried about the ability of our students to read and write, one would assume. It might also seem reasonable to take for granted that professionals interested in teen skills in reading books and writing papers would give close attention to those students who are now reading a fair amount of nonfiction and writing really exemplary research papers at the high school level.

At this point, expectations need to be altered a bit. Surely coaches of Adolescent Sports have a tremendous fascination with the best teen athletes in the country. There are lots of prizes and even scholarships for high school students who perform very well in football, soccer, basketball, baseball, etc., and there are even college scholarships for good teen cheerleaders. We might think it odd if all high school coaches cared about was physical education classes and even in those, only those student/athletes who were most un-coordinated and incompetent. Not that it is unimportant to worry about teens who are overweight and cannot take part in sports, but nevertheless, coaches tend to focus on the best athletes, and colleges and the society at large seem to think that is fine for them to do, and is even their job, some would say.

But when it comes to students who read well and write good term papers, the Literacy Community has no interest in them. It is only able to focus on the illiterate and incompetent among Adolescents, and their professional peers seem to think that is fine for them to do, and is even their real job. And it surely is important for them to help those who need help. They should do research and develop curricula and programs to help teens become more literate. They have been doing this for many decades, and yet more than a million of our high school graduates each and every year are in remedial (non-credit) courses when they are “admitted” (conditionally) to colleges around the country.

Perhaps the current approach to literacy training for young people might deserve a second look. The Chronicle of Higher Education surveyed college professors, 90% of whom reported that they thought the freshmen in their classes were not well prepared in reading, doing research, or writing term papers. Their high school teachers had thought they were well prepared, but college professors didn’t see it that way.

No doubt many of those students had the benefit of the Adolescent Literacy Initiatives of AdLit.org, National Council of Teachers of English, National Writing Project, Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA), Alliance for Excellent Education, Partnership for Reading, National Adolescent Literacy Coalition, Learning Point Associates, Education Development Center, Council of Chief State School Officers, Scholastic, Adolescent Literacy Coaching Project (ALCP), National Governors’ Association, Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, Adolescent Literacy Research Network, Adolescent Literacy Support Project, WGBH Adolescent Literacy website, and the International Reading Association, not to mention the many state and local literacy programs, and yet our students’ literacy still leaves a lot to be desired, even if they can graduate from high school.

To me it seems that, unlike coaches, the literacy pros are almost allergic to good academic work in reading and writing by our teens. I am not really sure why that would be the case, but in the last 20 years of working with exemplary secondary students of history from 44 states and 35 other countries, I have not found one single Literacy Organization or Literacy Program which had the slightest interest in their first-rate work, which I have been privileged to publish in 77 issues of The Concord Review so far. They have heard about it, but they don’t want to know about it, as far as I can tell.

It does seem foolish to me, that if they truly want to improve the reading and writing of adolescents, they don’t take a tiny bit of interest in exemplary reading and writing at the high school level, not only in the students’ work, but even perhaps in the work of the teachers who guided them to that level of excellence, just as high school coaches are interested in the best athletes and perhaps their coaches as well.

They could still spend the bulk of their time on grants given them to do “meta-analyses” of Literacy Strategies and the like, but it seems really stupid not to glance once or twice at very good written work by our most diligent teens (the Literate Adolescents).

Of course, I am biased. I believe that showing teachers and students the best term papers I can find will inspire them to try to reach for more success in literacy, and some of my authors agree with me: e.g. “When a former history teacher first lent me a copy of The Concord Review, I was inspired by the careful scholarship crafted by other young people. Although I have always loved history passionately, I was used to writing history papers that were essentially glorified book reports…As I began to research the Ladies’ Land League, I looked to The Concord Review for guidance on how to approach my task…In short, I would like to thank you not only for publishing my essay, but for motivating me to develop a deeper understanding of history. I hope that The Concord Review will continue to fascinate, challenge and inspire young historians for years to come.” Emma Curran Donnelly Hulse, Columbia Class of 2009; North Central High School (IN) Class of 2005……”The opportunity that The Concord Review presented drove me to rewrite and revise my paper to emulate its high standards. Your journal truly provides an extraordinary opportunity and positive motivation for high school students to undertake extensive research and academic writing, experiences that ease the transition from high school to college.” Pamela Ban, Harvard Class of 2012; Thomas Worthington High School (OH) Class of 2008…

But what do they know? They are just some of those literate adolescents in whom the professional adolescent literacy community seems to have no interest.

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

Core Knowledge Foundation Blog, Take That, AIG!

Published by Robert Pondiscio on March 20, 2009 in Education News and Students:

An upstate New York high school student could teach a course in character to the bonus babies of AIG. Nicole Heise of Ithaca High School was one of The Concord Review’s six winners of The Concord Review’s Emerson Prize awards for excellence this year. But as EdWeek’s Kathleen Kennedy Manzo tells the story, she sent back her prize, a check for $800, with this note:

“As you well know, for high school-aged scholars, a forum of this caliber and the incentives it creates for academic excellence are rare. I also know that keeping The Concord Review active requires resources. So, please allow me to put my Emerson award money to the best possible use I can imagine by donating it to The Concord Review so that another young scholar can experience the thrill of seeing his or her work published.”

The Concord Review publishes research papers by high school scholars. It’s a one-of-a-kind venue for its impressive young authors. Manzo notes TCR “has won praise from renowned historians, lawmakers, and educators, yet has failed to ever draw sufficient funding…It operates on a shoestring, as Founder and Publisher Will Fitzhugh reminds me often. Fitzhugh, who has struggled for years to keep the operation afloat, challenges students to do rigorous scholarly work and to delve deeply into history. His success at inspiring great academic work is juxtaposed against his failure to get anyone with money to take notice.”

Young Ms. Heise noticed. Anyone else?“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

Consortium for Varsity Academics® [2007]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

Students See Value in History-Writing Venue

Education Week “Curriculum Matters”

Kathleen Kennedy Manzo 17 March 2009:It is difficult to figure why some education ventures attract impressive financial and political support, while others flounder despite their value to the field. For years, I’ve written about The Concord Review and the really amazing history research papers it publishes from high school authors/scholars.

The Review has won praise from renowned historians, lawmakers, and educators, yet has failed to ever draw sufficient funding. The range of topics is as impressive as the volume of work by high school students: In 77 issues, the 846 published papers have covered topics from Joan of Arc to women’s suffrage, from surgery during the Civil War to the history of laser technology. (The papers average more than 7,000 words, and all have been vetted for accuracy and quality. Many of the students do these research papers for the experience and knowledge they gain, not for school credit.)

But here’s the kicker: It operates on a shoestring, as Founder and Publisher Will Fitzhugh reminds me often. Fitzhugh, who has struggled for years to keep the operation afloat, challenges students to do rigorous scholarly work and to delve deeply into history. His success at inspiring great academic work is juxtaposed against his failure to get anyone with money to take notice.

Well, if the grown-ups in the world have failed to recognize and reward the Review for its 22 years of contributions, the students themselves have not.

Fitzhugh has shared many of the letters he receives from students whose work has been published in The Concord Review over the years. Yesterday, he shared with me one of the most memorable of those letters, which arrived recently at his Sudbury, Massachusetts, office.

Nicole Heise won one of the Review’s Emerson Prize awards for excellence this year. The senior at Ithaca High School in Upstate New York sent the check back, with this note:

“As you well know, for high school-aged scholars, a forum of this caliber and the incentives it creates for academic excellence are rare. I also know that keeping The Concord Review active requires resources. So, please allow me to put my Emerson award money to the best possible use I can imagine by donating it to The Concord Review so that another young scholar can experience the thrill of seeing his or her work published.”

Degree of Difficulty

Will Fitzhugh

The Concord Review

7 March 2009

In gymnastics, performances are judged not just on execution but also on the degree of difficulty. The same system is used in diving and in ice skating. An athlete is of course judged on how well they do something, but their score also includes how hard it was to do that particular exercise.

One of the reasons, in my view, that more than a million of our high school graduates each year are in remedial courses after they have been accepted at colleges is that the degree of difficulty set for them in their high school courses has been too low, by college standards.

Surveys comparing the standards of high school teachers and college professors routinely discover that students who their teachers judge to be very well prepared, for instance in reading, research and writing, are seen as not very well prepared by college professors.

According to the Diploma to Nowhere report issued last summer by the Strong American Schools project, tens of thousands of students are surprised, embarrassed and depressed to find that, after getting As and Bs in their high school courses, even in the “hard” ones, they are judged to be not ready for college work and must take non-credit remedial courses to make up for the academic deficiencies that they naturally assumed they did not have.

If we could imagine a ten point degree-of-difficulty scale for high school courses, surely arithmetic would rank near the bottom, say at a one, and calculus would rank at the top, near a ten. Courses in Chinese and Physics, and perhaps AP European History, would be near the top of the scale as well.

When it comes to academic writing, however, and the English departments only ask their students for personal and creative writing, and the five-paragraph essay, they are setting the degree of difficulty at or near the bottom of the academic writing scale. The standard kind of writing might be the equivalent of having math students being blocked from moving beyond fractions and decimals.

Killers of Writing

“Even before students learn to write personal essays.” !!!

[student writers will now become “Citizen Composers,” Yancey says.]

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Eschool News

NCTE defines writing for the 21st century

New report offers guidance on how to update writing curriculum to include blogs, wikis, and other forms of communication

By Meris Stansbury, Associate Editor:Digital technologies have made writers of everyone.

The prevalence of blogs, wikis, and social-networking web sites has changed the way students learn to write, according to the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE)–and schools must adapt in turn by developing new modes of writing, designing new curricula to support these models, and creating plans for teaching these curricula.

“It’s time for us to join the future and support all forms of 21st-century literacies, [both] inside…and outside school,” said Kathleen Blake Yancey, a professor of English at Florida State University, past NCTE president, and author of a new report titled “Writing in the 21st Century.”

Just as the invention of the personal computer transformed writing, Yancey said, digital technologies–and especially Web 2.0 tools–have created writers of everyone, meaning that even before students learn to write personal essays, they’re often writing online in many different forms.

“This is self-sponsored writing,” Yancey explained. “It’s on bulletin boards and in chat rooms, in eMails and in text messages, and on blogs responding to news reports and, indeed, reporting the news themselves…This is a writing that belongs to the writer, not to an institution.”

College is Too Hard