Search Results for: We have the children

Adderall Suicide

The Sunday Times carries a long front-page article about a young man, Richard Fee, who committed suicide.

The article claims: “Medications like Adderall can markedly improve the lives of children and others with the disorder. But the tunnel-like focus the medicines provide has led growing numbers of teenagers and young adults to fake symptoms to obtain steady prescriptions for highly addictive medications that carry serious psychological dangers.”

But the article contains no evidence or proof of this claim that “growing numbers of teenagers and young adults” have faked symptoms. It’s a claim that would be hard to prove, because you’d have to rely on someone self-reporting that they lied, and anyone who admits that they lied is someone whose testimony might well be considered not 100% reliable.

The article goes on to blame Fee’s doctor and the drug manufacturer for his suicide. Fee himself, and his parents, don’t get blamed or scrutinized much at all.

How to Bridge the Generational Hope Divide

Almost all fifth- through 12th-graders — 95% — say it is likely they will have a better life than their parents. However, in a separate Gallup poll, half of U.S. adults aged 18 and older say they doubt today’s youth will have a better life than their parents.

This hope divide might limit the support that adults are willing to give children to help them reach their full potential. Undoubtedly, some adults will be tempted to explain to children that there are economic and political circumstances in the world that children can’t understand — ones that make their future look less rosy. Adults might even point out that many children are fantasizing about a future that is out of their reach. These cautions are grounded in some wisdom, but they also might be associated with the pessimism adults have about our own future, our personal vulnerabilities, or our profound inability to predict the future.

To bridge the hope divide we have to do three things.

Strife and Progress: Portfolio Strategies For Managing Urban Schools

Paul Hill, Christine Campbell, Betheny Gross, via a kind Deb Britt email:

This new book from Paul Hill and colleagues Christine Campbell and Betheny Gross explains the underlying idea of the portfolio strategy. Based on findings from studies of portfolio school districts, the book shows how mayors and other city leaders have introduced the strategy, compares different cities’ implementation, tells about the civic coalitions that come together to support it, and analyzes the intense and colorful conflicts it can set off. The book also offers a clear, concise explanation of the main components of the strategy and how they work together under a model of continuous improvement to create a unified strategy.

One core theme is that entrenched interests are sure to fight any reform initiative that is strong enough to make a difference in big city education. The authors explain how the fact that no adult group’s interests perfectly match those of children makes conflict inevitable and often productive.

The book also takes stock of results to date, which are mixed, though generally positive in the cities that have pursued the strategy most aggressively. However, Hill, Campbell, and Gross make clear that early reform leaders like Joel Klein in New York and Paul Pastorek in Louisiana have been too optimistic, assuming that the results would be so obviously good that careful assessment was unnecessary. The authors show what kinds of proof are necessary for a portfolio strategy and how far short the available evidence falls.

Act 10 will hurt state, education in long run

Retired High School Teacher Rose Locander:

The public schools in Wisconsin are some of the best in the country. Over the years, businesses have moved into this state knowing their employees will be able to feel confident sending their children to the local public schools.

What will happen as the years go by and the public schools in this state lose their ability to meet the expectations of excellence in education? Exactly what will attract businesses to this state when the public schools are no longer quality schools? Are we going to woo companies with the promise of our wonderful weather?

Too many of us have taken our public schools for granted. From early childhood through high school, we have become used to well-trained, dedicated teachers, quality educational programs, identification and early intervention of learning issues and a host of other resources found only in the public schools. We expect this of our public schools, but with Act 10, these opportunities that were of great value to all of our children will continue to disappear.Related: www.wisconsin2.org

Special needs vouchers are an empty promise

Gary E. Myrah, Janis Serak and Lisa Pugh: As a new legislative session gets underway, a statewide group concerned about the education of students with disabilities is waving a yellow caution flag. Parents often say what is most important to them about their children’s education is that they receive quality instruction, they are safe and […]

Ritalin Gone Wrong

THREE million children in this country take drugs for problems in focusing. Toward the end of last year, many of their parents were deeply alarmed because there was a shortage of drugs like Ritalin and Adderall that they considered absolutely essential to their children’s functioning.

But are these drugs really helping children? Should we really keep expanding the number of prescriptions filled?

In 30 years there has been a twentyfold increase in the consumption of drugs for attention-deficit disorder.

As a psychologist who has been studying the development of troubled children for more than 40 years, I believe we should be asking why we rely so heavily on these drugs.

Attention-deficit drugs increase concentration in the short term, which is why they work so well for college students cramming for exams. But when given to children over long periods of time, they neither improve school achievement nor reduce behavior problems. The drugs can also have serious side effects, including stunting growth.

Families and how to survive them: How differences that isolate individuals can unite humanity

Far from the Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity. By Andrew Solomon. Scribner; 962 pages; $37.50. To be published in Britain by Chatto & Windus in February; £30. Buy from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk

ANDREW SOLOMON never knew a time when he was not gay. He chose pink balloons over blue ones and described operas on the school bus rather than trade baseball cards. He was teased at school for being effete and ignored by children issuing party invitations. In his teens Mr Solomon began to suffer from depression. His parents, supportive and understanding, would have preferred their son to be straight and encouraged him to marry a woman and have a family. The recognition that he was gay came only when he understood that gayness was not a matter of behaviour, but of identity; and identity is learned by observing and being part of a subculture outside the family.

The case for school choice

This year over 41,000 students took advantage of Wisconsin’s open-enrollment policy to transfer to public schools outside their home district, according to the Department of Public Instruction. An additional 37,000 students attend over 200 charter schools. Over 25,000 students participate in the Milwaukee and Racine voucher programs, while 137,000 students attend over 900 private schools. Clearly demand for choice by parents and students is strong.

Yet choice is not without its critics. Some argue school choice is an effort to “privatize” public education. But Wisconsin is constitutionally required to provide public schools. And certainly families who are happy with traditional public schools (of which there are many) are not going to abandon them.

This fear of “privatization” begs the question: Is the goal of public education to achieve an educated public, or the creation of a certain type of school? Focusing on form over function is a mistake.

Others believe choice starves public schools of critical funding. But as the number of families exercising choice over the past few decades has grown dramatically, so have public school expenditures. According to the Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance, from 1999 to 2011 real inflation-adjusted per pupil public school expenditures in Wisconsin have increased almost 16 percent, from $10,912 to $12,653.

In addition, a University of Arkansas study on the Milwaukee voucher program estimates it saved Wisconsin taxpayers nearly $52 million in 2011 due to the voucher amount being far less than what Milwaukee public schools typically spend per student. Arguing that choice has hurt public school finances is not supported by the evidence.

Another frequent criticism of school choice is the objection to taxpayer money being spent on private educational institutions. But our government spends taxpayer dollars on products and services from private companies all the time. Why is it OK to pay private contractors to build our schools, private publishing companies to provide the books and private transport companies to bus our children, but when the teacher or administrator is not a government employee we cry foul?

Our focus should be on educating children and preparing them for life, through whatever school form that might take.

Innovative lenses will boost learning

Sir, You identify the life-changing potential of glasses for children in the developing world, shortlisted for the Design Museum’s Design of the Year award (“Design shortlist balances form against function“, January 14), but credit for the design belongs not to me personally but to the team at the Centre for Vision in the Developing World, of which I am CEO, and consultants Goodwin Hartshorn.

The true innovation of these glasses is not that their size is adjustable but that the wearer can – under the supervision of, for instance, a schoolteacher – adjust the power of each lens to correct his or her own vision.

Clinical trials (references are available at cvdw.org) have shown that young people aged 12-18 as well as adults are able to achieve good correction by this process of self-refraction. We estimate that today at least 60m short-sighted children in the developing world lack access to accurate vision correction.

Transfer Students & London Achievement

I wrote a piece yesterday on the continued astonishing rise of London’s state schools. One of my brilliant colleagues posed an interesting question: what happens if a child moves into London?

Below, I have published how children who lived outside London at the age of 11 went on to do in their GCSEs (using our usual point score) at the age of 16.

I have divided this set of pupils twice: first, by whether they had moved into London by the age of 16 or not and second by how well they did in standardised tests at the age of 11.

ORCA K-8 teachers join boycott of district-required (MAP) exams

Linda Shaw: Eleven teachers and instructional assistants at ORCA K-8 have decided that they, too, will boycott district-required tests known as the MAP, according to ORCA teacher Matt Carter. The Orca staffers join the staff at Garfield High, where all teachers who were scheduled to administer the Measures of Academic Progress exams are refusing, with […]

Will longer school year help or hurt US students?

Did your kids moan that winter break was way too short as you got them ready for the first day back in school? They might get their wish of more holiday time off under proposals catching on around the country to lengthen the school year.

But there’s a catch: a much shorter summer vacation.

Education Secretary Arne Duncan, a chief proponent of the longer school year, says American students have fallen behind the world academically.

“Whether educators have more time to enrich instruction or students have more time to learn how to play an instrument and write computer code, adding meaningful in-school hours is a critical investment that better prepares children to be successful in the 21st century,” he said in December when five states announced they would add at least 300 hours to the academic calendar in some schools beginning this year.

New Mexico Kids Count Report

4MB PDF via New Mexico Voices for Children:

The national KIDS COUNT Program, using the National Assessment for Educational Progress (NAEP), a standardized test that allows comparability of reading scores across states, ranks New Mexico 50th–dead last–among the states in 4th grade reading proficiency. Only about 20 percent–just two out of every ten New Mexico 4th graders–can read at a proficient level. If we consider the results from New Mexico’s own 3rd grade reading proficiency test, the results are not any more encouraging. While in six school districts as many as 70 percent to 80 percent of 3rd graders score at a “proficient and above” level, in too many others–more than one-third of our public school districts – only 50 percent or less of the 3rd graders read proficiently or above. This does not bode well for many students’ potential to succeed as they progress into higher grade levels.

This concern seems justified when we consider the low math proficiency rates of New Mexico’s 8th graders. In only 11 out of the state’s 89 public school districts do 60 percent or more of the 8th graders score at a “proficient or above” level. In two-thirds (60) of the school districts less than half the students can do math at the required level.

Given that skill in mathematics is considered vital for 21st century technical jobs, low proficiency in mathematics is alarming in its implications for New Mexico’s future workforce capacity.

These low proficiency scores have an effect on the state’s high school graduation rate. A 2012 report from the U.S. Department of Education ranked only one state lower than New Mexico in terms of the on-time high school graduation rate.5 The state’s graduation rate, 63 percent (only 56 percent for economically disadvantaged students), means that more than one-third (37 percent) of our youth do not graduate from high school within four years.

There are better performance rates, however. Some public school districts-most of them in small communities-have graduation rates of 90 percent and above.

Third Grade Follow-up to the Head Start Impact Study

Looking across the full study period, from the beginning of Head Start through 3rd grade, the evidence is clear that access to Head Start improved children’s preschool outcomes across developmental domains, but had few impacts on children in kindergarten through 3rd grade. Providing access to Head Start was found to have a positive impact on the types and quality of preschool programs that children attended, with the study finding statistically significant differences between the Head Start group and the control group on every measure of children’s preschool experiences in the first year of the study. In contrast, there was little rd evidence of systematic differences in children’s elementary school experiences through 3 grade, between children provided access to Head Start and their counterparts in the control group.

In terms of children’s well-being, there is also clear evidence that access to Head Start had an impact on children’s language and literacy development while children were in Head Start. These effects, albeit modest in magnitude, were found for both age cohorts during their first year of admission to the Head Start program. However, these early effects rapidly dissipated in elementary school, with only a single impact remaining at the end of 3rd grade for children in each age cohort.

With regard to children’s social-emotional development, the results differed by age cohort and by the person describing the child’s behavior. For children in the 4-year-old cohort, there were no observed impacts through the end of kindergarten but favorable impacts reported by parents and unfavorable impacts reported by teachers emerged at the end of 1st and 3rd grades.

One unfavorable impact on the children’s self-report emerged at the end of 3rd grade. In contrast to the 4-year-old cohort, for the 3-year-old cohort there were favorable impacts on parent- reported social emotional outcomes in the early years of the study that continued into early elementary school. However, there were no impacts on teacher-reported measures of social- emotional development for the 3-year-old cohort at any data collection point or on the children’s self-reports in 3rd grade.

In Support of The Milwaukee Public Schools

In his Jan. 6 column, Alan J. Borsuk says that a new vision for education in Milwaukee is needed to get beyond the stale and failed answers of the past. He is right.

Milwaukee has had voucher schools since 1990, longer than any school district in the nation. Students in the voucher schools perform no better than those in the public schools.

Milwaukee has had charter schools for about 20 years. Students in the charter schools do no better than those in the public schools.

As the other sectors have grown, Milwaukee Public Schools has experienced sharply declining enrollment. At the same time, the number of students with disabilities is far greater in the public schools than in either the voucher or charter schools. The latter are unable or unwilling to take the children who are most challenging and most expensive to educate. Thus, MPS is “competing” with two sectors that skim off the ablest students and reject the ones they don’t want. Most people would say this is not a level playing field.

Parenthood & Life Expectancy

PARENTS often complain that their lives are being shortened by the stress of having children, yet numerous studies suggest the opposite: that it is the childless who die young, not those who have procreated. Such research has, however, failed to find out whether it is the actual absence of children which causes early mortality or whether, rather, it is brought about by the state of mind that leads some people not to have children in the first place.

To resolve the point Esben Agerbo of the University of Aarhus in Denmark and his colleagues conducted an investigation that tried to take the question of wanting children out of the equation, by looking only at those people who had demonstrated a desire to be parents by undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF). They discovered, as they report in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, that there really does seem to be something about the presence of kids which makes a difference to the length of people’s lives.

State law change keeps Wisconsin principal evaluations under wraps

A change in state law creating a new teacher and principal evaluation system also exempts those evaluations from public disclosure, even though the public has previously had access to principal evaluations.

Open government advocates were unaware of the new exemption to the state’s open records law, but said the Legislature should revisit the principal evaluation issue.

“I hope that there would be some willingness to reassess this decision,” said Bill Lueders, president of the Wisconsin Freedom of Information Council. “There are few issues that matter more to ordinary people than the quality of their children’s education. For that reason the evaluations of the top school official, the principal, have traditionally been open, and we think they should stay that way.”

Jim Lynch, executive director of the Association of Wisconsin School Administrators, said the group of state education leaders who designed the evaluation system recommended the records exemption in the law based on the purpose of the new system, which is not to compare educators.

“The focus of this is to have assessments meant for organizations to make human resources decisions and for people to learn and grow,” Lynch said. “That is done best in a confidential environment.”

Math in a Child’s World: Policy and Practical Challenges for Preschool Mathematics

Several studies have shown that basic math concepts acquired at a preschool level–including counting, sorting, and recognizing simple patterns and shapes–are the most powerful predictors of later learning, even more than reading.

But preschools face many challenges in implementing a high quality math curriculum, including:

The paucity of math content in preschool teacher preparation;

The uneven quality or lack of professional development and in-service learning opportunities for teachers;

Linking what children learn in preschool with what they are expected to learn in the K-3 grades;

The barriers imposed by “math anxiety” among many preschool teaching staff

5 Most Inspirational Videos of 2012

These five short videos will remind you what’s important in life and work.

This has been a difficult few days for everybody, especially for those of us who have children in primary school.

I had already selected the following five clips as the most inspirational and motivational videos of the year.

I think they are testament to the fact that the human spirit is greater than tragedy and to remind us that the reason we all work so hard is because we want to make a difference in the world.

2013 Wisconsin DPI Superintendent and Madison School Board Candidates

Patrick Marley & Erin Richards:

“I’ve been frustrated with the fact that our educational system continues to go downhill even with all the money the Legislature puts into it,” he said.

Pridemore said he will release more details about his educational agenda in forthcoming policy statements and has several education bills in the drafting phase. Asked if he believed schools should have armed teachers, he said that was a matter that should be left entirely to local school boards to decide.

Evers, who has been school superintendent since 2009, is seeking a second term. He has previously served as a teacher, principal, local school superintendent and deputy state schools superintendent.

Wisconsin’s education landscape has undergone some major changes during his tenure, including significant reductions in school spending and limits on collective bargaining for public workers that weakened teachers unions, which have supported Evers in the past.

Evers wants to redesign the funding formula that determines aid for each of Wisconsin’s 424 school districts and to provide more aid to schools. Also, he wants to reinvigorate technical education and to require all high schools to administer a new suite of tests that would offer a better way to track students’ academic progress and preparation for the ACT college admissions exam.Don Pridemore links: SIS, Clusty, Blekko, Google and link farming. Incumbent Tony Evers: SIS, Clusty, Blekko, Google and link farming.

Matthew DeFour:School Board president James Howard, the lone incumbent seeking re-election, faces a challenge from Greg Packnett, a legislative aide active with the local Democratic Party. The seats are officially nonpartisan.

Two candidates, low-income housing provider Dean Loumos and recently retired Madison police lieutenant Wayne Strong, are vying for Moss’ seat.

The race for Cole’s seat will include a primary on Feb. 19, the first one for a Madison School Board seat in six years. The candidates are Sarah Manski, a Green Party political activist who runs a website that encourages buying local; Ananda Mirilli, social justice coordinator for the YWCA who has a student at Nuestro Mundo Community School; and T.J. Mertz, an Edgewood College history instructor and local education blogger whose children attend West High and Randall Elementary schools.

Jerry Brown pushes new funding system for California schools

Gov. Jerry Brown is pushing hard to overhaul California’s convoluted school funding system. His plan has two major objectives: Give K-12 districts greater control over how they spend money, and send more dollars to impoverished students and English learners.

Studies show that such children require more public help to reach the same level of achievement as their well-off peers. But as rich and poor communities alike clamor for money in the wake of funding cuts, Brown’s plan could leave wealthy suburbs with fewer new dollars than poorer urban and rural districts.

That makes perfect sense, said Michael W. Kirst, president of the State Board of Education and a Stanford University professor who co-wrote a 2008 paper that became the model for Brown’s proposal.

“Low-income people have less resources to invest in their children,” Kirst said. “A lot of investment comes from parental ability to buy external things for their kids that provide a better education. In the case of low-income groups, they can’t buy tutors, after-school programs or summer experiences.”

Is big disruption good for urban school districts?

My colleague Emma Brown has been looking closely at Chancellor Kaya Henderson’s plans to close one of every six traditional D.C. public schools.

In one piece, she cited activists who raised the possibility that the education system of our nation’s capital might, as a consequence of the downsizing, be split in two: Charter schools would rule the low-income neighborhoods, while regular public schools would thrive only in the affluent areas where achievement rates remain high.

This is not some wild nightmare. Education finance lawyer Mary Levy, a careful and longtime analyst of D.C. schools, said at one meeting: “What we are rapidly approaching is a [public school system] concentrated west of Rock Creek Park and perhaps around Capitol Hill, and a separate charter school system filled by lottery in most of the rest of the city.”

This is upsetting to many D.C. residents and people in the region who work or have lived in the city. But to some reformers, it is a great opportunity, a way to let parent choice energize the schools and give urban children more chances for success.

Like the neighborhood, not the school? Author understands your problem.

In my 30 years writing about schools, one reader question outnumbers all others: “I like where I live, but I have kids now and the local school doesn’t look good to me. What should I do?”

I tell them how to investigate their neighborhood school. I explain that children of education-focused parents learn much no matter what school they attend. Then I advise them to go with their gut. Even if everybody thinks their local school is great, if it doesn’t feel right they should send their kids elsewhere.

I’ve done a long magazine piece and lots of columns on this, but I have never seen the issue dissected as well as in a new book by Washington-area parent Michael J. Petrilli, “The Diverse Schools Dilemma: A Parent’s Guide to Socioeconomically Mixed Public Schools.” It is deep, up to date, blessedly short (119 pages) and wonderfully personal. He shares all the frustrations and embarrassments he and his wife suffered while looking for schools for their two young sons.

Common Core: The Totalitarian Temptation

Jonah Goldberg

Liberal Fascism

New York: Doubleday, 2007, pp. 326-327

…Progressive education has two parents, Prussia and John Dewey. The kindergarten was transplanted into the United States from Prussia in the nineteenth century because American reformers were so enamored of the order and patriotic indoctrination young children received outside the home (the better to weed out the un-American traits of immigrants). One of the core tenets of the early kindergarten was the dogma that “the government is the true parent of the children, the state is sovereign over the family.” The progressive followers of John Dewey expanded this program to make public schools incubators of a national religion. They discarded the militaristic rigidity of the Prussian model, but retained the aim of indoctrinating children. The methods were informal, couched in the sincere desire to make learning “fun,” “relevant,” and “empowering.” The self-esteem obsession that saturates our schools today harks back to the Deweyan reforms from before World War II. But beneath the individualist rhetoric lies a mission for democratic social justice, a mission Dewey himself defined as a religion. For other progressives, capturing children in schools was part of the larger effort to break the backbone of the nuclear family, the institution most resistant to political indoctrination.

National Socialist educators had a similar mission in mind. And as odd as it might seem, they also discarded the Prussian discipline of the past and embraced self-esteem and empowerment in the name of social justice. In the early days of the Third Reich, grade-schoolers burned their multicolored caps in a protest against class distinctions. Parents complained, “We no longer have rights over our children.” According to the historian Michael Burleigh, “Their children became strangers, contemptuous of monarchy or religion, and perpetually barking and shouting like pint-sized Prussian sergeant-majors…Denunciation of parents by children was encouraged, not least by schoolteachers who set essays entitled ‘What does your family talk about at home?'”

Now, the liberal project Hillary Clinton represents is in no way a Nazi project. The last thing she would want is to promote ethnic nationalism, anti-Semitism, or aggressive wars of conquest. But it must be kept in mind that while these things were of enormous importance to Hitler and his ideologues, they were in an important sense secondary to the underlying mission and appeal of Nazism, which was to create a new politics and a new nation committed to social justice, radical egalitarianism (albeit for “true Germans”), and the destruction of the traditions of the old order. So while there are light-years of distance between the programs of liberals and those of Nazis or Italian Fascists or even the nationalist progressives of yore, the underlying impulse, the totalitarian temptation, is present in both.

The Chinese Communists under Mao pursued the Chinese way, the Russians under Stalin followed their own version of communism in one state. But we are still comfortable observing that they were both communist nations. Hitler wanted to wipe out the Jews; Mussolini wanted no such thing. And yet we are comfortable calling both fascists. Liberal fascists don’t want to mimic generic fascists or communists in myriad ways, but they share a sweeping vision of social justice and community and the need for the state to realize that vision. In short, collectivists of all stripes share the same totalitarian temptation to create a politics of meaning; what differs between them–and this is the most crucial difference of all–is how they act upon that temptation.============

“Teach by Example”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

www.tcr.org/blog

Stop Subsidizing Obesity

Mark Bittman Not long ago few doctors – not even pediatricians – concerned themselves much with nutrition. This has changed, and dramatically: As childhood obesity gains recognition as a true health crisis, more and more doctors are publicly expressing alarm at the impact the standard American diet is having on health. “I never saw Type […]

Global Burden of Disease Study 2010

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2010 (GBD 2010) is the largest ever systematic effort to describe the global distribution and causes of a wide array of major diseases, injuries, and health risk factors. The results show that infectious diseases, maternal and child illness, and malnutrition now cause fewer deaths and less illness than they did twenty years ago. As a result, fewer children are dying every year, but more young and middle-aged adults are dying and suffering from disease and injury, as non-communicable diseases, such as cancer and heart disease, become the dominant causes of death and disability worldwide.

Since 1970, men and women worldwide have gained slightly more than ten years of life expectancy overall, but they spend more years living with injury and illness.

GBD 2010 consists of seven Articles, each containing a wealth of data on different aspects of the study (including data for different countries and world regions, men and women, and different age groups), while accompanying Comments include reactions to the study’s publication from WHO Director-General Margaret Chan and World Bank President Jim Yong Kim. The study is described by Lancet Editor-in-Chief Dr Richard Horton as “a critical contribution to our understanding of present and future health priorities for countries and the global community.”

No more Flori-duh. State’s fourth-grade readers go from bottom of the nation to top of the world

Mike Thomas, via a kind reader’s email:

Kids in Singapore and Finland have long distinguished themselves on international academic tests, leaving American kids far, far, far behind.

They would rule the 21st Century while our kids would assemble snow globes, sew sneakers, man the call centers and figure out how to pay their parents’ entitlements on 93 cents a day.

If things weren’t bad enough, now we have the results of international fourth grade reading assessments. And not only were the usual suspects at the top of the list, we have a new nation to rub its superiority in our face, a nation that bested even Singapore and Finland.

The kids there not only significantly outperformed American kids, they had almost triple the percent of students reading at an advanced level when compared to the international average.The PIRLS results are better than you may realize.

Last week, the results of the 2011 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) were published. This test compared reading ability in 4th grade children.

U.S. fourth-graders ranked 6th among 45 participating countries. Even better, US kids scored significantly better than the last time the test was administered in 2006.

There’s a small but decisive factor that is often forgotten in these discussions: differences in orthography across languages.

Lots of factors go into learning to read. The most obvious is learning to decode–learning the relationship between letters and (in most languages) sounds. Decode is an apt term. The correspondence of letters and sound is a code that must be cracked.

In some languages the correspondence is relatively straightforward, meaning that a given letter or combination of letters reliably corresponds to a given sound. Such languages are said to have a shallow orthography. Examples include Finnish, Italian, and Spanish.

In other languages, the correspondence is less consistent. English is one such language. Consider the letter sequence “ough.” How should that be pronounced? It depends on whether it’s part of the word “cough,” “through,” “although,” or “plough.” In these languages, there are more multi-letter sound units, more context-depenent rules and more out and out quirks.

Montgomery superintendent shows courage in denouncing standardized tests

For more than a decade, school standardized tests have been the magic keys that were supposed to unlock the door to a promised realm of American students able to read and do sums as well as their counterparts in Asia and Europe.

A generation of U.S. education reformers has assured us that if we would just rely mostly on test scores and other hard data to guide decisions, then all manner of good results would ensue. Foundations gave millions of dollars to encourage it. The Obama administration embraced the cause, lest it stand accused of short-changing kids.

It was always a fairy tale. Tests are necessary, of course, but the mania for them has become self-defeating. They don’t account for the vast differences in children’s social, economic and family backgrounds. Good teachers give up on proven classroom techniques and instead “teach to the test.”

Now, finally, somebody with standing is getting attention for denouncing the madness.

The truth-teller is one of our own from the Washington region, Montgomery County Superintendent Joshua P. Starr. He has only been here for a year and a half, but he arrived with an impressive résumé and is emerging as a credible national voice urging a more reasoned and deliberate path to educational progress.

Homework Emancipation Proclamation

The French President’s emancipation proclamation regarding homework may give heart not only to les enfants de la patrie but to the many opponents of homework in this country as well–the parents and the progressive educators who have long insisted that compelling children to draw parallelograms, conjugate irregular verbs, and outline chapters from their textbooks after school hours is (the reasons vary) mindless, unrelated to academic achievement, negatively related to academic achievement, and a major contributor to the great modern evil, stress. M. Hollande, however, is not a progressive educator. He is a socialist. His reason for exercising his powers in this area is to address an inequity. He thinks that homework gives children whose parents are able to help them with it–more educated and affluent parents, presumably–an advantage over children whose parents are not. The President wants to give everyone an equal chance.

Homework is an institution roundly disliked by all who participate in it. Children hate it for healthy and obvious reasons; parents hate it because it makes their children unhappy, but God forbid they should get a check-minus or other less-than-perfect grade on it; and teachers hate it because they have to grade it. Grading homework is teachers’ never-ending homework. Compared to that, Sisyphus lucked out.Via Laura Waters

Don’t blame teachers for achievement gap

With all due respect to John Legend and Geoff Canada, firing teachers is not the solution to the achievement gap in Madison schools. The two spoke in Madison last week, prompting Friday’s article “Reformers: City schools need institutional change.”

I have been a substitute teacher in many classrooms since 2005 in Madison schools. What do I see?

Teachers who come early and stay late. Teachers who keep a stash of granola bars in their desks for the child who doesn’t make it to school on time for breakfast. Aides who lovingly attend to children with serious special needs.

I see 5-year-olds so out of control they can disrupt a classroom in minutes. Kids who live in their cars.

A class of their own: From Obama to Hague, foreign dignitaries are flocking to Myanmar. But as the country grapples with democratic change, its education system risks holding back the next generation

Nayaka sat wrapped in a blanket and an extra set of monk’s robes, shivering in his Swiss hotel room. He pulled three hats on to his shaved head, and wound a thick woollen scarf around his face. The temperature outside was probably in the mid-teens – after all, it was only September. Yet it was the coldest he had ever been.

In spite of the late hour, there was no way he was going to bed. On the other side of the world, tens of thousands of his countrymen had taken to the streets in what many people thought was the start of a revolution, and an end to Myanmar’s military dictatorship. Alongside the crowds of students marched thousands of his fellow Buddhist monks, decked out in their burnt orange robes and red velvet sandals. But U Nayaka would watch it all unfold on the TV news. It was perhaps fitting. U Nayaka (“U” is a Burmese honorific) has spent the past 20 years trying to avoid politics. Instead he has devoted himself to being the headmaster of one of the country’s largest schools, Phaung Daw Oo, where he and his brother help to educate more than 6,000 impoverished children every day. (His visit to Switzerland in late 2007 was for an international education conference.) Yet despite his distaste for politics, U Nayaka – and many others like him – are now key players in the country’s move towards democracy.

Abolish Social Studies

Michael Knox Beran, via Will Fitzhugh:

Emerging as a force in American education a century ago, social studies was intended to remake the high school. But its greatest effect has been in the elementary grades, where it has replaced an older way of learning that initiated children into their culture [and their History?] with one that seeks instead to integrate them into the social group. The result was a revolution in the way America educates its young. The old learning used the resources of culture to develop the child’s individual potential; social studies, by contrast, seeks to adjust him to the mediocrity of the social pack.

Why promote the socialization of children at the expense of their individual development? A product of the Progressive era, social studies ripened in the faith that regimes guided by collectivist social policies could dispense with the competitive striving of individuals and create, as educator George S. Counts wrote, “the most majestic civilization ever fashioned by any people.” Social studies was to mold the properly socialized citizens of this grand future. The dream of a world regenerated through social planning faded long ago, but social studies persists, depriving children of a cultural rite of passage that awakened what Coleridge called “the principle and method of self-development” in the young.

The poverty of social studies would matter less if children could make up its cultural deficits in English [and History?] class. But language instruction in the elementary schools has itself been brought into the business of socializing children and has ceased to use the treasure-house of culture to stimulate their minds. As a result, too many students today complete elementary school with only the slenderest knowledge of a culture that has not only shaped their civilization but also done much to foster individual excellence.

In 1912, the National Education Association, today the largest labor union in the United States, formed a Committee on the Social Studies. In its 1916 report, The Social Studies in Secondary Education, the committee opined that if social studies (defined as studies that relate to “man as a member of a social group”) took a place in American high schools, students would acquire “the social spirit,” and “the youth of the land” would be “steadied by an unwavering faith in humanity.” This was an allusion to the “religion of humanity” preached by the French social thinker Auguste Comte, who believed that a scientifically trained ruling class could build a better world by curtailing individual freedom in the name of the group. In Comtian fashion, the committee rejected the idea that education’s primary object was the cultivation of the individual intellect. “Individual interests and needs,” education scholar Ronald W. Evans writes in his book The Social Studies Wars, were for the committee “secondary to the needs of society as a whole.”

The Young Turks of the social studies movement, known as “Reconstructionists” because of their desire to remake the social order, went further. In the 1920s, Reconstructionists like Counts and Harold Ordway Rugg argued that high schools should be incubators of the social regimes of the future. Teachers would instruct students to “discard dispositions and maxims” derived from America’s “individualistic” ethos, wrote Counts. A professor in Columbia’s Teachers College and president of the American Federation of Teachers, Counts was for a time enamored of Joseph Stalin. After visiting the Soviet Union in 1929, he published A Ford Crosses Soviet Russia, a panegyric on the Bolsheviks’ “new society.” Counts believed that in the future, “all important forms of capital” would “have to be collectively owned,” and in his 1932 essay “Dare the Schools Build a New Social Order?,” he argued that teachers should enlist students in the work of “social regeneration.”

Like Counts, Rugg, a Teachers College professor and cofounder of the National Council for the Social Studies, believed that the American economy was flawed because it was “utterly undesigned and uncontrolled.” In his 1933 book The Great Technology, he called for the “social reconstruction” and “scientific design” of the economy, arguing that it was “now axiomatic that the production and distribution of goods can no longer be left to the vagaries of chance–specifically to the unbridled competitions of self-aggrandizing human nature.” There “must be central control and supervision of the entire [economic] plant” by “trained and experienced technical personnel.” At the same time, he argued, the new social order must “socialize the vast proportion” of wealth and outlaw the activities of “middlemen” who didn’t contribute to the “production of true value.”

Rugg proposed “new materials of instruction” that “shall illustrate fearlessly and dramatically the inevitable consequence of the lack of planning and of central control over the production and distribution of physical things. . . . We shall disseminate a new conception of government–one that will embrace all of the collective activities of men; one that will postulate the need for scientific control and operation of economic activities in the interest of all people; and one that will successfully adjust the psychological problems among men.”

Rugg himself set to work composing the “new materials of instruction.” In An Introduction to Problems of American Culture, his 1931 social studies textbook for junior high school students, Rugg deplored the “lack of planning in American life”:

“Repeatedly throughout this book we have noted the unplanned character of our civilization. In every branch of agriculture, industry, and business this lack of planning reveals itself. For instance, manufacturers in the United States produce billions’ of dollars worth of goods without scientific planning. Each one produces as much as he thinks he can sell, and then each one tries to sell more than his competitors. . . . As a result, hundreds of thousands of owners of land, mines, railroads, and other means of transportation and communication, stores, and businesses of one kind or another, compete with one another without any regard for the total needs of all the people. . . . This lack of national planning has indeed brought about an enormous waste in every outstanding branch of industry. . . . Hence the whole must be planned.

Rugg pointed to Soviet Russia as an example of the comprehensive control that America needed, and he praised Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan, which resulted in millions of deaths from famine and forced labor. The “amount of coal to be mined each year in the various regions of Russia,”

Rugg told the junior high schoolers reading his textbook,

“is to be planned. So is the amount of oil to be drilled, the amount of wheat, corn, oats, and other farm products to be raised. The number and size of new factories, power stations, railroads, telegraph and telephone lines, and radio stations to be constructed are planned. So are the number and kind of schools, colleges, social centers, and public buildings to be erected. In fact, every aspect of the economic, social, and political life of a country of 140,000,000 people is being carefully planned! . . . The basis of a secure and comfortable living for the American people lies in a carefully planned economic life.”

During the 1930s, tens of thousands of American students used Rugg’s social studies textbooks.

Toward the end of the decade, school districts began to drop Rugg’s textbooks because of their socialist bias. In 1942, Columbia historian Allan Nevins further undermined social studies’ premises when he argued in The New York Times Magazine that American high schools were failing to give students a “thorough, accurate, and intelligent knowledge of our national past–in so many ways the brightest national record in all world history.” Nevins’s was the first of many critiques that would counteract the collectivist bias of social studies in American high schools, where “old-fashioned” history classes have long been the cornerstone of the social studies curriculum.

Yet possibly because school boards, so vigilant in their superintendence of the high school, were not sure what should be done with younger children, social studies gained a foothold in the primary school such as it never obtained in the secondary school. The chief architect of elementary school social studies was Paul Hanna, who entered Teachers College in 1924 and fell under the spell of Counts and Rugg. “We cannot expect economic security so long as the [economic] machine is conceived as an instrument for the production of profits for private capital rather than as a tool functioning to release mankind from the drudgery of work,” Hanna wrote in 1933.

Hanna was no less determined than Rugg to reform the country through education. “Pupils must be indoctrinated with a determination to make the machine work for society,” he wrote. His methods, however, were subtler than Rugg’s. Unlike Rugg’s textbooks, Hanna’s did not explicitly endorse collectivist ideals. The Hanna books contain no paeans to central planning or a command economy. On the contrary, the illustrations have the naive innocence of the watercolors in Scott Foresman’s Dick and Jane readers. The books depict an idyllic but familiar America, rich in material goods and comfortably middle-class; the fathers and grandfathers wear suits and ties and white handkerchiefs in their breast pockets.

Not only the pictures but the lessons in the books are deceptively innocuous. It is in the back of the books, in the notes and “interpretive outlines,” that Hanna smuggles in his social agenda by instructing teachers how each lesson is to be interpreted so that children learn “desirable patterns of acting and reacting in democratic group living.” A lesson in the second-grade text Susan’s Neighbors at Work, for example, which describes the work of police officers, firefighters, and other public servants, is intended to teach “concerted action” and “cooperation in obeying commands and well-thought-out plans which are for the general welfare.” A lesson in Tom and Susan, a first-grade text, about a ride in grandfather’s red car is meant to teach children to move “from absorption in self toward consideration of what is best in a group situation.” Lessons in Peter’s Family, another first-grade text, seek to inculcate the idea of “socially desirable” work and “cooperative labor.”

Hanna’s efforts to promote “behavior traits” conducive to “group living” would be less objectionable if he balanced them with lessons that acknowledge the importance of ideals and qualities of character that don’t flow from the group–individual exertion, liberty of action, the necessity at times of resisting the will of others. It is precisely Coleridge’s principle of individual “self-development” that is lost in Hanna’s preoccupation with social development. In the Hanna books, the individual is perpetually sunk in the impersonality of the tribe; he is a being defined solely by his group obligations. The result is distorting; the Hanna books fail to show that the prosperous America they depict, if it owes something to the impulse to serve the community, owes as much, or more, to the free striving of individuals pursuing their own ends.

Hanna’s spirit is alive and well in the American elementary school. Not only Scott Foresman but other big scholastic publishers–among them Macmillan/McGraw-Hill and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt–publish textbooks that dwell continually on the communal group and on the activities that people undertake for its greater good. Lessons from Scott Foresman’s second-grade textbook Social Studies: People and Places (2003) include “Living in a Neighborhood,” “We Belong to Groups,” “A Walk Through a Community,” “How a Community Changes,” “Comparing Communities,” “Services in Our Community,” “Our Country Is Part of Our World,” and “Working Together.” The book’s scarcely distinguishable twin, Macmillan/McGraw-Hill’s We Live Together (2003), is suffused with the same group spirit. Macmillan/McGraw-Hill’s textbook for third-graders, Our Communities (2003), is no less faithful to the Hanna model. The third-grade textbooks of Scott Foresman and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (both titled Communities) are organized on similar lines, while the fourth-grade textbooks concentrate on regional communities. Only in the fifth grade is the mold shattered, as students begin the sequential study of American history; they are by this time in sight of high school, where history has long been paramount.

Today’s social studies textbooks will not turn children into little Maoists. The group happy-speak in which they are composed is more fatuous than polemical; Hanna’s Reconstructionist ideals have been so watered down as to be little more than banalities. The “ultimate goal of the social studies,” according to Michael Berson, a coauthor of the Houghton Mifflin Harcourt series, is to “instigate a response that spreads compassion, understanding, and hope throughout our nation and the global community.” Berson’s textbooks, like those of the other publishers, are generally faithful to this flabby, attenuated Comtism.

Yet feeble though the books are, they are not harmless. Not only do they do too little to acquaint children with their culture’s ideals of individual liberty and initiative; they promote the socialization of the child at the expense of the development of his own individual powers. The contrast between the old and new approaches is nowhere more evident than in the use that each makes of language. The old learning used language both to initiate the child into his culture and to develop his mind. Language and culture are so intimately related that the Greeks, who invented Western primary education, used the same word to designate both: paideia signifies both culture and letters (literature). The child exposed to a particular language gains insight into the culture that the language evolved to describe–for far from being an artifact of speech only, language is the master light of a people’s thought, character, and manners. At the same time, language–particularly the classic and canonical utterances of a people, its primal poetry–[and its History?] has a unique ability to awaken a child’s powers, in part because such utterances, Plato says, sink “furthest into the depths of the soul.”

Social studies, because it is designed not to waken but to suppress individuality, shuns all but the most rudimentary and uninspiring language. Social studies textbooks descend constantly to the vacuity of passages like this one, from People and Places:

“Children all around the world are busy doing the same things. They love to play games and enjoy going to school. They wish for peace. They think that adults should take good care of the Earth. How else do you think these children are like each other? How else do you think they are like you?”

The language of social studies is always at the same dead level of inanity. There is no shadow or mystery, no variation in intensity or alteration of pitch–no romance, no refinement, no awe or wonder. A social studies textbook is a desert of linguistic sterility supporting a meager scrub growth of commonplaces about “community,” “neighborhood,” “change,” and “getting involved.” Take the arid prose in Our Communities:

“San Antonio, Texas, is a large community. It is home to more than one million people, and it is still growing. People in San Antonio care about their community and want to make it better. To make room for new roads and houses, many old trees must be cut down. People in different neighborhoods get together to fix this by planting.”

It might be argued that a richer and more subtle language would be beyond third-graders. Yet in his Third Eclectic Reader, William Holmes McGuffey, a nineteenth-century educator, had eight-year-olds reading Wordsworth and Whittier. His nine-year-olds read the prose of Addison, Dr. Johnson, and Hawthorne and the poetry of Shakespeare, Milton, Byron, Southey, and Bryant. His ten-year-olds studied the prose of Sir Walter Scott, Dickens, Sterne, Hazlitt, and Macaulay [History] and the poetry of Pope, Longfellow, Shakespeare, and Milton.

McGuffey adapted to American conditions some of the educational techniques that were first developed by the Greeks. In fifth-century BC Athens, the language of Homer and a handful of other poets formed the core of primary education. With the emergence of Rome, Latin became the principal language of Western culture and for centuries lay at the heart of primary- and grammar-school education. McGuffey had himself received a classical education, but conscious that nineteenth-century America was a post-Latin culture, he revised the content of the old learning even as he preserved its underlying technique of using language as an instrument of cultural initiation and individual self-development. He incorporated, in his Readers, not canonical Latin texts but classic specimens of English prose and poetry [and History].

Because the words of the Readers bit deep–deeper than the words in today’s social studies textbooks do–they awakened individual potential. The writer Hamlin Garland acknowledged his “deep obligation” to McGuffey “for the dignity and literary grace of his selections. From the pages of his readers I learned to know and love the poems of Scott, Byron, Southey, and Words- worth and a long line of the English masters. I got my first taste of Shakespeare from the selected scenes which I read in these books.” Not all, but some children will come away from a course in the old learning stirred to the depths by the language of Blake or Emerson. But no student can feel, after making his way through the groupthink wastelands of a social studies textbook, that he has traveled with Keats in the realms of gold.

It might be objected that primers like the McGuffey Readers were primarily intended to instruct children in reading and writing, something that social studies doesn’t pretend to do. In fact, the Readers, like other primers of the time, were only incidentally language manuals. Their foremost function was cultural: they used language both to introduce children to their cultural heritage [including their History] and to stimulate their individual self-culture. The acultural, group biases of social studies might be pardonable if cultural learning continued to have a place in primary-school English instruction. But primary-school English–or “language arts,” as it has come to be called–no longer introduces children, as it once did, to the canonical language of their culture; it is not uncommon for public school students today to reach the fifth grade without having encountered a single line of classic English prose or poetry. Language arts has become yet another vehicle for the socialization of children. A recent article by educators Karen Wood and Linda Bell Soares in The Reading Teacher distills the essence of contemporary language-arts instruction, arguing that teachers should cultivate not literacy in the classic sense but “critical literacy,” a “pedagogic approach to reading that focuses on the political, sociocultural, and economic forces that shape young students’ lives.”

For educators devoted to the social studies model, the old learning is anathema precisely because it liberates individual potential. It releases the “powers of a young soul,” the classicist educator Werner Jaeger wrote, “breaking down the restraints which hampered it, and leading into a glad activity.” The social educators have revised the classic ideal of education expressed by Pindar: “Become what you are” has given way to “Become what the group would have you be.” Social studies’ verbal drabness is the means by which its contrivers starve the self of the sustenance that nourishes individual growth. A stunted soul can more easily be reduced to an acquiescent dullness than a vital, growing one can; there is no readier way to reduce a people to servile imbecility than to cut them off from the traditions of their language [and their History], as the Party does in George Orwell’s 1984.

Indeed, today’s social studies theorists draw on the same social philosophy that Orwell feared would lead to Newspeak. The Social Studies Curriculum: Purposes, Problems, and Possibilities, a 2006 collection of articles by leading social studies educators, is a socialist smorgasbord of essays on topics like “Marxism and Critical Multicultural Social Studies” and “Decolonizing the Mind for World-Centered Global Education.” The book, too, reveals the pervasive influence of Marxist thinkers like Peter McLaren, a professor of urban schooling at UCLA who advocates “a genuine socialist democracy without market relations,” venerates Che Guevara as a “secular saint,” and regards the individual “self” as a delusion, an artifact of the material “relations which produced it”–“capitalist production, masculinist economies of power and privilege, Eurocentric signifiers of self/other identifications,” all the paraphernalia of bourgeois imposture. For such apostles of the social pack, Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” Milton’s and Tennyson’s “soul within,” Spenser’s “my self, my inward self I mean,” and Wordsworth’s aspiration to be “worthy of myself” are expressions of naive faith in a thing that dialectical materialism has revealed to be an accident of matter, a random accumulation of dust and clay.

The test of an educational practice is its power to enable a human being to realize his own promise in a constructive way. Social studies fails this test. Purge it of the social idealism that created and still inspires it, and what remains is an insipid approach to the cultivation of the mind, one that famishes the soul even as it contributes to what Pope called the “progress of dulness.” It should be abolished.

School Choice vs. ‘Familiar Images’

“For Young Latino Readers, an Image Is Missing.”

So goes the headline of a recent New York Times story that cites a lot of multiculturalist mumbo-jumbo to explain the learning gap between white and Hispanic students.

“Hispanic students now make up nearly a quarter of the nation’s public school enrollment,” notes the Times, “yet nonwhite Latino children seldom see themselves in books written for young readers.” The paper would have us believe that this contributes to the underperformance of Latinos on standardized tests. According to Department of Education data for 2011, 18% of Hispanic fourth graders were proficient in reading, compared with 44% of white fourth graders.

“Education experts and teachers who work with large Latino populations say that a lack of familiar images could be an obstacle as young readers work to build stamina and deepen their understanding of story elements like character motivation,” says the article.

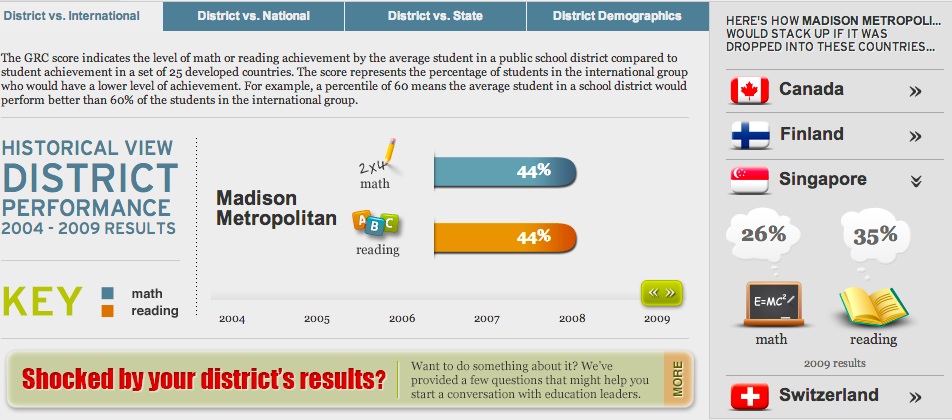

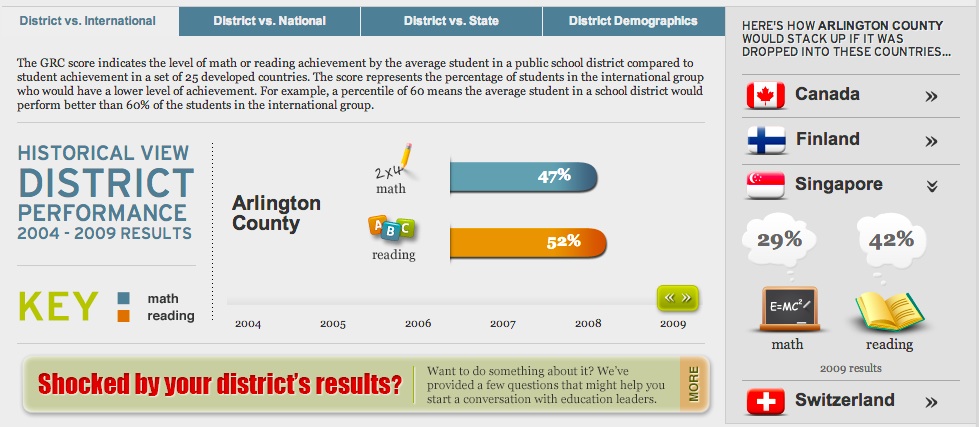

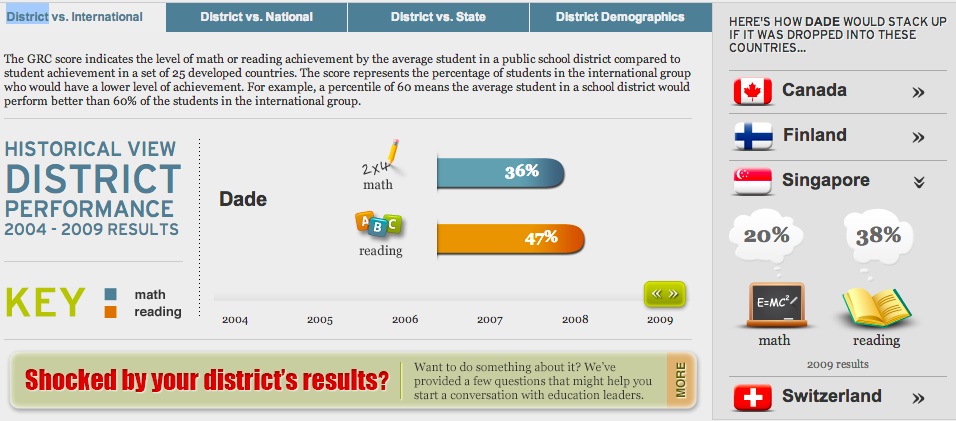

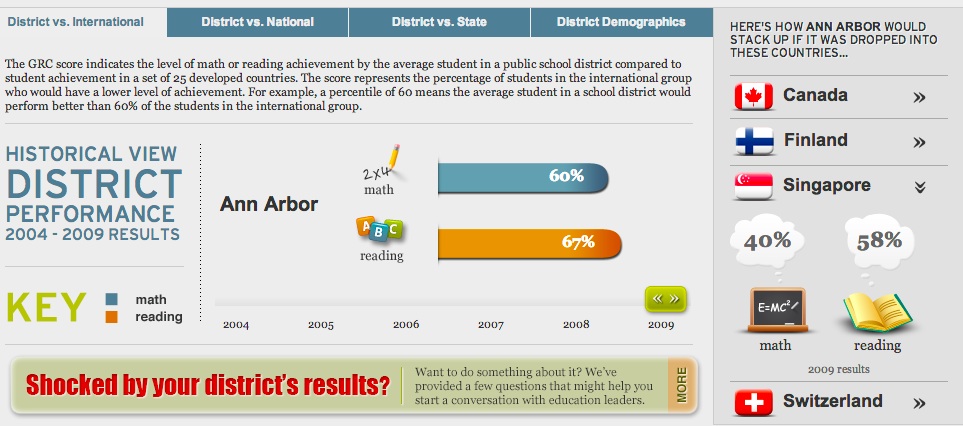

Madison & US School Districts vs. The World

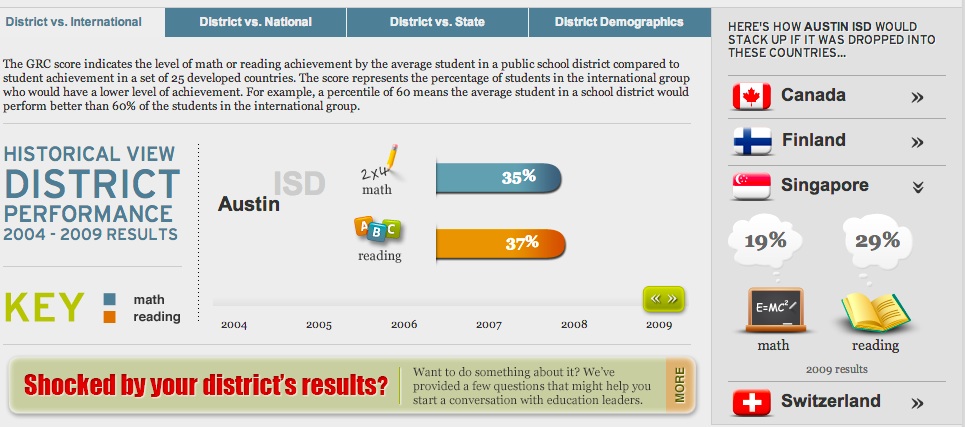

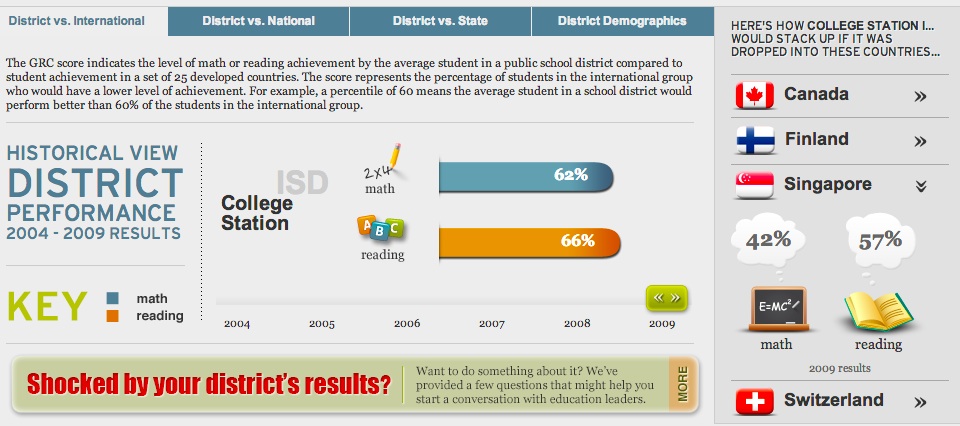

The Global Report Card, via a kind reader’s email:

Ever wonder how your public school district stacks up when compared to the rest of the world? What about how your district compares to your state or even the nation?

Tap or click on the images to view larger versions. Learn more about Madison & Wisconsin versus the world at www.wisconsin2.org.

How Does Your Child’s School Rank Against the Rest of the World?

If your kids are in a good American public school, chances are you know it. (In fact, it’s probably the reason you traded in that urban loft for the property taxes of the suburbs.) But what if you woke up one morning and found that a Wizard of Oz-style tornado had dropped your entire district down in the middle of Singapore or Finland? How would your children’s test scores measure up then?

That’s more or less what the Bush Institute wants to you to imagine as you click through its Global Report Card, an interactive graphic that lets you rank your district against 25 other countries. “When you tell people there are problems in education, elites will usually think, ‘Ah, that refers to those poor kids in big cities. It doesn’t have anything to do with me,'” says Jay P. Greene, head of the department of education reform at the University of Arkansas and one of the lead researchers behind the Global Report Card. “The power of denial is so great that people don’t think a finding really has anything to do with them unless you actually name their town.”

Education forum shows divide persists over Madison’s achievement gap strategy

But divisions over strategy, wrapped in ideology, loom as large as ever. The mere mention that the education forum and summit were on tap drew online comments about the connection of school reformers to the American Legislative Exchange Council, an organization that generates model legislation for conservative causes.

Conspiracy theorists, opponents retorted.

Democratic state Rep. Brett Hulsey walked out early from the fundraising luncheon because he didn’t like what Canada and Legend were saying about the possibility of reform hinging on the ability to fire ineffective teachers.

Thomas J. Mertz, a parent and college instructor who blogs on education issues, expressed in a phone interview Friday his indignation over “flying in outside agitators who have spent no time in our schools and telling us what our problems are.”

Mertz said he also was concerned by the involvement of the Madison School District with events delivering anti-union, anti-public education, pro-charter school messages. The school district, for its part, took pains to say that the $5,000 it donated in staff time was for a Friday workshop session and that it had no involvement with the appearances by Canada and Legend.

Madison doesn’t need a summit to whip up excitement over the achievement gap issue, Mertz said when I asked if the Urban League events didn’t at least accomplish that. “It’s at the point where there’s more heat than light,” he said. “There’s all this agitation, but the work is being neglected.”

That’s a charge that School Board President James Howard, who says that the district might decide to mimic some of the practices presented at the summit, flatly denies. “We’re moving full speed ahead,” he said.

….

Caire told me that the school district and teachers union aren’t ready to give up their control over the school system. “The teachers union should be the entity that embraces change. The resources they get from the public should be used for the children’s advantage. What we’re saying is, ‘Be flexible, look at that contract and see how you can do what works.'”

Madison Teachers Inc. head John Matthews responded in an email to me that MTI contracts often include proposals aimed at improving education, in the best interests of students. “What Mr. Caire apparently objects to is that the contract provides those whom MTI represents due process and social justice, workplace justice that all employees deserve.”

If Caire has his way, Madison — and the state — are up for another round of debate over how radically to change education infrastructure to boost achievement of students of color.

Why Asians are Better than Americans at Math

Since elementary school, we learned basic mathematics skills as little children. As we grew older, our math improved as we learned new concepts. Yet have people ever wondered why Americans lag behind Eastern Asian countries, such as China, in math? The answer might not easily be what you think:

The answer lies not only in the practice that Asian students receive but also, surprisingly, in the language we speak. Examine the following numbers: 8,2,4,6,7,5,1. Now look away for twenty seconds, and try to memorize the order of the numbers presented. Research has shown that you have a 50% chance of accurately memorizing that sequence perfectly, if you speak English.

Yet for those who speak Chinese, it is almost assured that you will get that sequence right. The reason is not due to intelligence, but actually the phonetics of our languages. Our brain is programmed to store numbers in a repetitive loop that lasts for only a short period of time. Chinese speakers are able to fit those 7 numbers into that span of time, while English speakers cannot. Hence, the Chinese speakers can memorize those numbers at a much more efficient rate than English speakers. How is this important?

Suburban Milwaukee schools take on minority students’ achievement gap

Means, the superintendent of Mequon-Thiensville schools and the most prominent African-American involved in education in Milwaukee suburban schools, is pushing to have constructive conversations about a subject few have wanted to discuss publicly: the lower achievement overall of minority children in suburban schools, at a time when the number of minority children in those schools is rising.

Means’ presentation came on a recent evening before 35 people at Wauwatosa West High School, a session hosted by Wauwatosa and West Allis-West Milwaukee school officials.

A few weeks earlier, Means made a similar presentation at Whitefish Bay High School. He has made the same pitch in the district where he works and just about anywhere else people will listen to him.

He is spearheading the launch of a collaborative effort involving at least a half-dozen suburban districts aimed at taking new runs at improving the picture.

The gaps are widespread and persistent. Black kids and Hispanic kids do not do as well in school as their white peers, even in the schools with the highest incomes, best facilities, most stable teaching staffs and highest test scores.

But Means told the Wauwatosa audience that schools shouldn’t focus on societal factors they can’t control. There are things schools can do, he said, such as making more meaningful commitments to high expectations for all students, insisting on rigor in classrooms, and ensuring that culturally responsive teaching styles and relationship-building are prevalent.

Means advocated three broad routes for schools:Mequon-Thiensville’s 2012-2013 budget is $51,286,130 or $14,024 for 3,657 students. Madison will spend $15,132 per student during the 2012-2013 school year.

Schools try longer days, academic years

Kids may groan when their parents hire a tutor or drag them to music lessons. But some educators say that extra learning gives them a leg up on students who can’t afford after-school activities. So today, school and government officials, nonprofits and the Ford Foundation announced that almost 20,000 students will spend more time in school, starting next fall.

“The question we have is can we give all children the opportunity that our most affluent kids have,” said Luis Ubinas, president of the Ford Foundation.

To answer that question, the Ford Foundation and the National Center on Time and Learning have signed up dozens of public schools for a pilot program. They can opt for a longer school day or year.

Randi Weingarten heads the American Federation of Teachers union. She’s backing the program, albeit cautiously.

Disrupting Class

My mission is to create a student-centric education system so that all children have an education that allows them to find their passions and fulfill their human potential, just as mine did for me. Today’s education system doesn’t do that; it’s modeled after a factory and is built to standardize the way we teach and test. The problem with this is that every child has different learning needs at different times. If we hope to educate each child effectively–an imperative in today’s society–then we need a system that can customize to meet each child’s unique needs. With the growth of online learning–a disruptive innovation–we stand at an unprecedented moment in human history where education is being transformed. If we leverage this innovation properly, over the next decade, we will be able to deliver a high-quality, customized learning experience to all children no matter their circumstances and transform not just the delivery of education, but the hopes, dreams, and realities for all children.

Michael B. Horn is the cofounder and Education Executive Director of Innosight Institute (http://www.innosightinstitute.org/), a non-profit think tank devoted to applying the theories of disruptive innovation to solve problems in the social sector. He is the coauthor of Disrupting Class: How Disruptive Innovation Will Change the Way the World Learns (http://www.amazon.com/Disrupting-Class-Expanded-Edition-Disruptive/dp/0071749101/). Tech&Learning magazine named him to its list of the 100 most important people in the creation and advancement of the use of technology in education.

About TEDx, x = independently organized event

In the spirit of ideas worth spreading, TEDx is a program of local, self-organized events that bring people together to share a TED-like experience. At a TEDx event, TEDTalks video and live speakers combine to spark deep discussion and connection in a small group. These local, self-organized events are branded TEDx, where x = independently organized TED event. The TED Conference provides general guidance for the TEDx program, but individual TEDx events are self-organized. (Subject to certain rules and regulations.)

A Passionate, Unapologetic Plea for Creative Writing in Schools

“I’m not sure if eight-year-olds should be permitted to have death or murder references in their short stories,” said a New York City public school principal to me at the end of the day today. “But I’ll set a meeting with my teachers tomorrow to discuss your views and theirs and see where we get.”

Three hours later, I am still moved and humbled by the principal’s thoughtful consideration of a topic so new and strange to her. We had just started a residency in her school. We had discussed a no-censorship approach for this workshop and the children had immediately come to life when they were told they could write a fictional story about anything they wanted.

But by week two, some of the teachers were concerned to see the heavy material that emerged, here and there, throughout the grade, from the special ed class to the “gifted and talented.” Human beings young and old love exploring dark, fantastical themes. But what are we supposed to think when our youngest members do it? When should our admiration turn to worry, and when does it become a school’s responsibility?

It is not easy to teach creative writing within the confinement of school. It is not easy to tackle the issues that arise, and it’s not easy to learn how to teach fiction and memoir writing well. But it is possible. And many teachers are doing it, and doing it well, across the country.

Helping Parents Score on the Homework Front

Homework can be as monumental a task for parents as it is for children. So what’s the best strategy to get a kid to finish it all? Where’s the line between helping with an assignment and doing the assignment? And should a parent nag a procrastinating preteen to focus–or let the child fall behind and learn a hard lesson?

As schools pile on more homework as early as preschool, many parents are confused about how to assist, says a 2012 research review at Johns Hopkins University. Some 87% of parents have a positive view of helping with homework, and see it as a beneficial way to spend time with their kids, says the study, co-authored by Joyce Epstein, a research professor of sociology and education.

Yet sometimes parental intervention may actually hurt student performance. During the middle-school years, such help was linked to lower academic achievement in a 2009 review of 50 studies by researchers at Duke University. Parents who apply too much pressure, explain material in different ways than teachers or intervene without being asked may undermine these students’ growing desire for independence, according to the study, published in Developmental Psychology.

Treating our kids like suspects

One of the best lines in the movie “Lean on Me” was delivered by high school Principal Joe Clark, who told a custodian to “tear down” the cages in the cafeteria that were used to protect the cooks from the students.

“If you treat them like animals, that’s exactly how they will behave,” said Clark, portrayed by Morgan Freeman.

Clark is right, and that’s why Milwaukee Public Schools should not subject thousands of children to daily metal detector scans.

Metal detectors and hand-held wands only give educators, students and parents the false illusion that their schools are safe, when there is little proof that they cut down on violence.

The district says it does the scans to be proactive in light of the workplace and school shootings that have taken place across the country since 1999’s attack at Columbine High School in Colorado.

MPS spokesman Tony Tagliavia said, “We’d much rather have a conversation on why we scan instead of having the conversation on why we didn’t.”

In the Book Bag, More Garden Tools

In the East Village, children planted garlic bulbs and harvested Swiss chard before Thanksgiving. On the other side of town, in Greenwich Village, they learned about storm water runoff, solar energy and wind turbines. And in Queens, students and teachers cultivated flowers that attract butterflies and pollinators.

Across New York City, gardens and miniature farms — whether on rooftops or at ground level — are joining smart boards and digital darkrooms as must-have teaching tools. They are being used in subjects as varied as science, art, mathematics and social studies. In the past two years, the number of school-based gardens registered with the city jumped to 232, from 40, according to GreenThumb, a division of the parks department that provides schools with technical support.

But few of them come with the credential of the 2,400-square-foot garden at Avenue B and Fifth Street in the East Village, on top of a red-brick building that houses three public schools: the Earth School, Public School 64 and Tompkins Square Middle School. Michael Arad, the architect who designed the National September 11 Memorial in Lower Manhattan, was a driving force behind the garden, called the Fifth Street Farm.

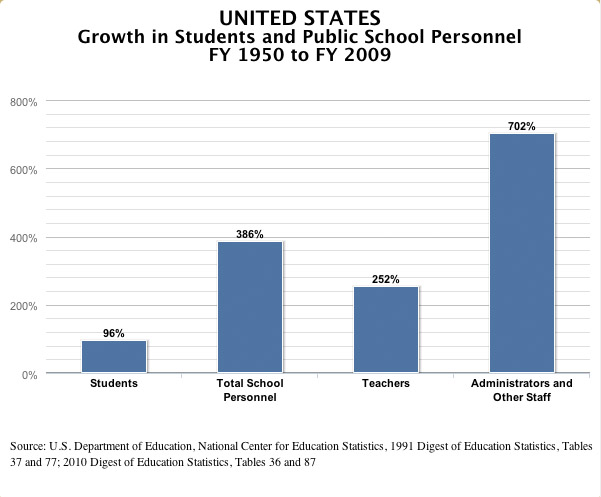

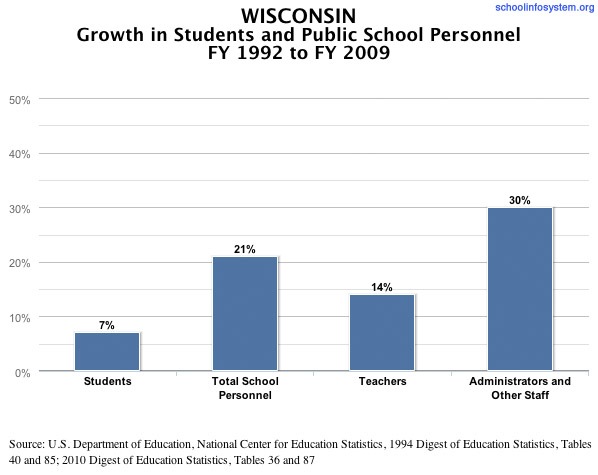

On US K-12 Staff Growth: Greater than Student Growth